The restoration of camera-ready artwork for advertisements from 1965 to 1981

260 camera-ready artworks for advertisements dating from 1968 to 1981, owned by the Pirelli Historical Archive, were restored in 2016-17. The 260 items involved in the recent operation used materials and techniques typical of the period and of the sector in which they were designed and made.

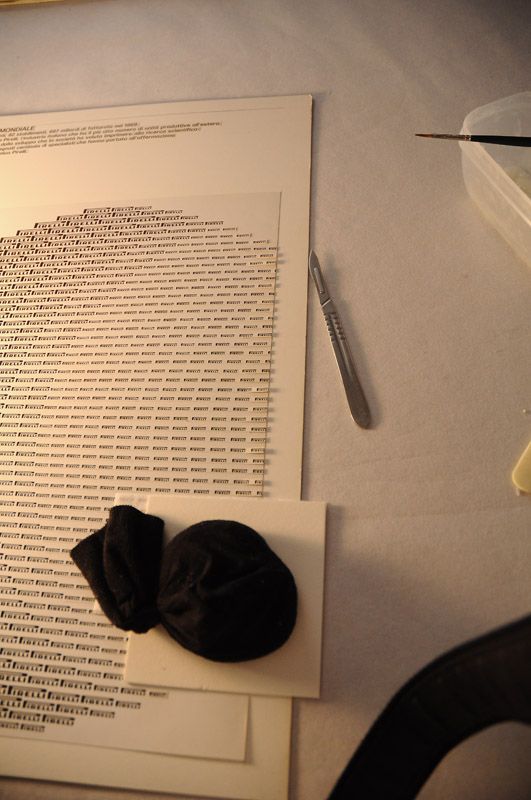

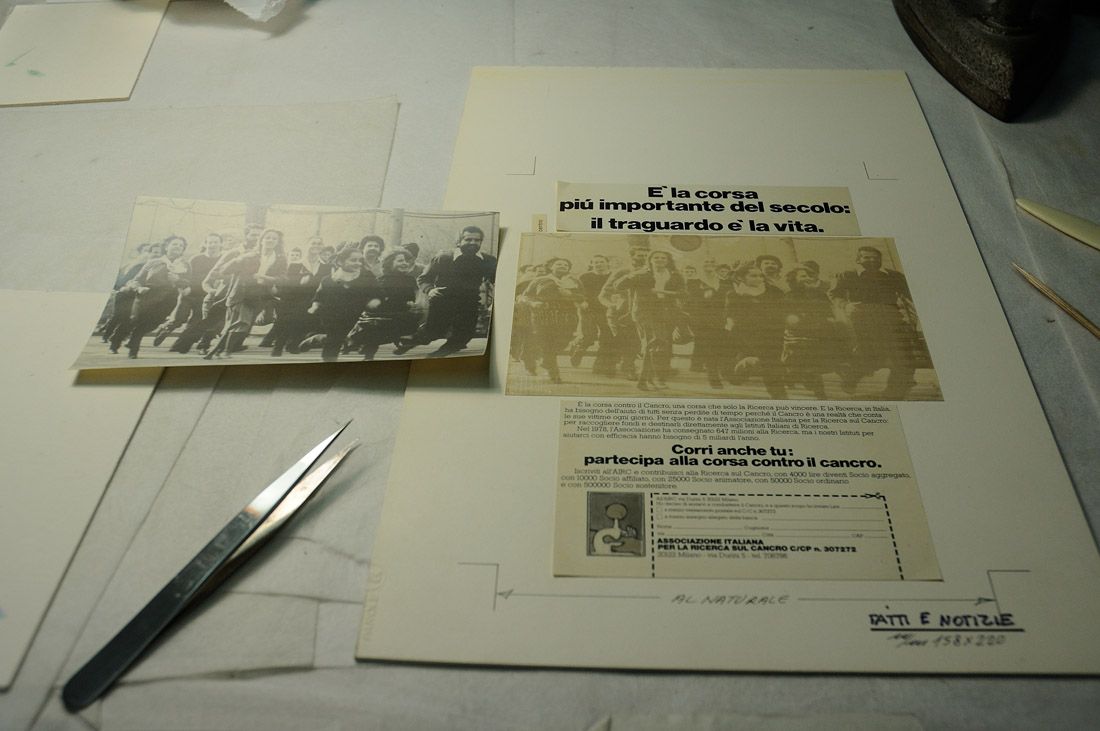

In the late 1960s, the pictorial and caricatural/cartoon-style rendering of previous artists and draughtsmen began to disappear, and there was a shift to more graphic images with ample space given to text. Direct manual intervention was considerably reduced, and few artworks were made using tempera or India ink, while photographs and printed characters were used in a majority of cases. The restoration thus made it possible to go back in time through graphic studies to examine the work methods adopted before the advent of computers.

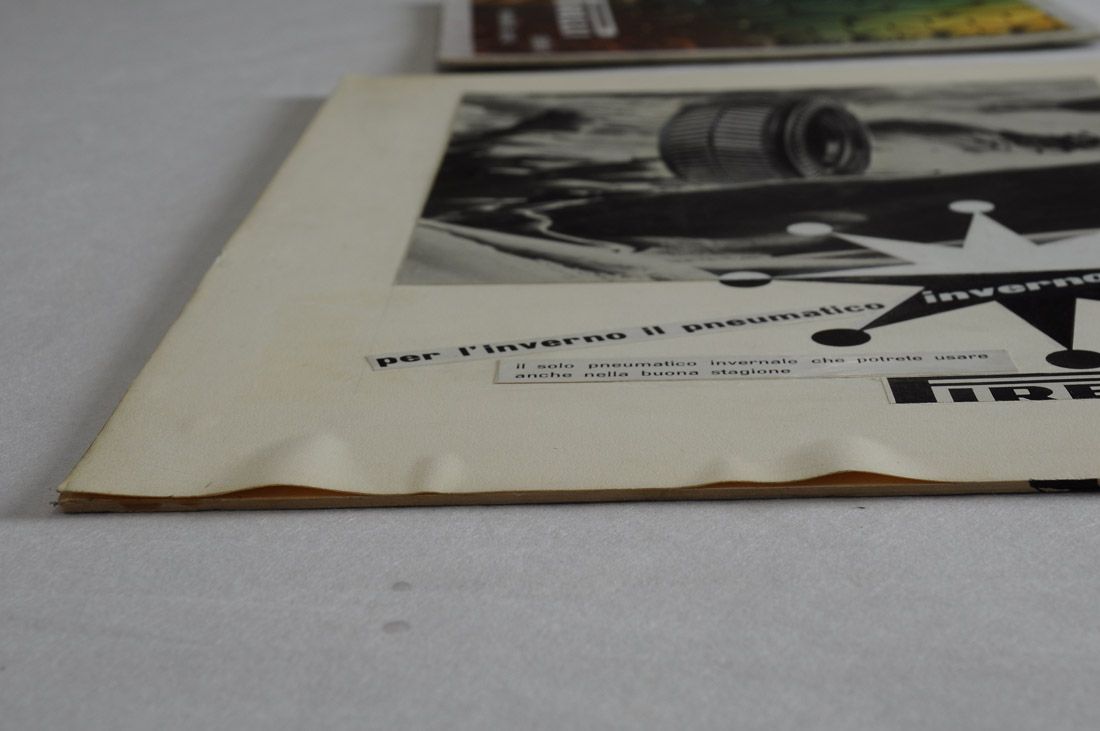

Most of the artworks in this group consist of a number of superimposed layers, with the main part of the image made on Shoeller card, which was the support most commonly used in graphic art studios, as well as in the world of contemporary art at the time. This card is about 1.5 mm thick, with an inner core consisting of several layers in wood paste, lined on the front with a very smooth, relatively non-porous, ivory-coloured coated paper and on the back with green-blue paper. In many cases, also the factory trademark, made with an embossing stamp, can be seen. Together with considerable deposits of dust (removed by surface cleaning using a Wishab sponge), the main form of damage found on the cards, caused by improper handling and conservation methods, was the presence of indentations on the edges and corners, and flaking of the constituent layers of the card. This required re-adhesion of the layers and consolidation of the edges, using Japanese starch paste between the layers of card, and mixed glue consisting of methylcellulose and an acrylic emulsion to reinforce, protect and impermeabilise the edges.

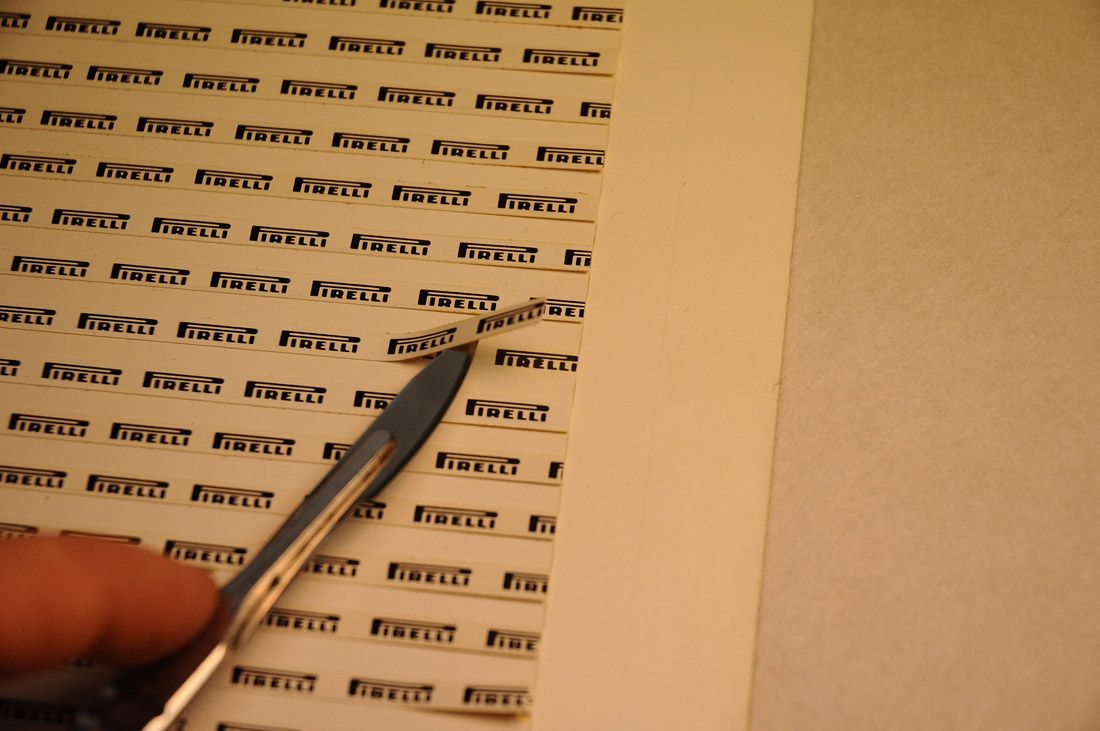

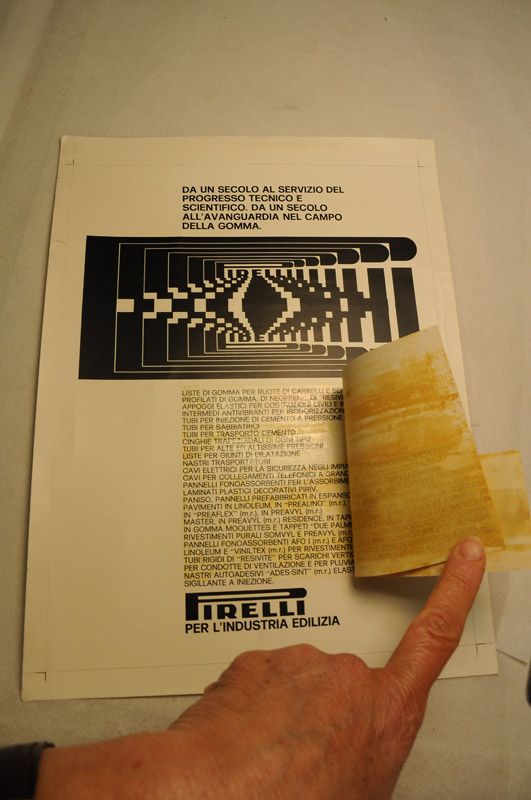

The smooth, non-absorbent coated side of the card was the one used to compose the image for the artwork: as we have seen, there were a few works in tempera and a certain number in India ink, but in most cases the images were obtained by assembling papers of various types, photographic or otherwise, with photographic or typographical prints, cut out in various shapes and glued to the card. The most evident influence of art schools can be seen in the type of adhesive used. It was not difficult to discover that most of the gluing had been done with the famous (as it certainly was back then) Cow Gum glue. This took its name not from actual cows, but from its inventor, Mr Cow. This glue had the consistency of honey and a strong smell of solvent, and it was sold in a red and white tin with the word “Cow” written conspicuously across it. It was spread with a white plastic spatula, one of which I still have today. Reading various graphics websites and talking with architects and designers, I have found that, before computers were used, all firms and studios – and not just art students – made ample use of it. The texts, images and various elements of the composition were cut out (often using the card itself as a support, and indeed many superficial cuts can be seen on the Pirelli artworks) and then glued onto the card. The advantage of Cow Gum over water-based glues was that it did not wrinkle the paper, and it also gave a certain amount of time for repositioning the various elements if one wanted to modify the composition. At the time of use, Cow Gum was transparent, but of course no one knew back then what changes it would undergo over the years. As it oxidises over time, it undergoes a change in colour, which also affects the paper it is applied to, creating brown traces where the glue was spread (particularly on the backs). It also loses its adhesive power, leading to the partial or complete detachment of the various elements stuck to the card.

This was the situation that most of the artwork involved in the restoration was in: in the past, some of the small, detached pieces were lost, but the restoration work fortunately meant it was possible to intervene in time to check the degree of adhesion and to fasten all the remaining pieces. Even just slight pressure with the tip of a scalpel was enough to detach the parts where the adhesive had become completely oxidised. This meant it was possible to recover and consolidate all the applied elements, using Japanese starch paste after mechanically eliminating the remains of the old Cow Gum that had oxidised and turned to dust. The re-adhesions were carried out completely or partially (depending on the areas where the loss of adhesion had occurred), or at least on the corners and edges, in order to avoid further loss in the future. It was not, however, possible to remove the brown stains caused by oxidation, which had become irreversible. As mentioned, many of the cut-outs glued to the cards were photographs of various types, both glossy and semi-matt, which were used both for printing images and for many of the printed texts. Limited use was made of silver-salt prints, which are recognisable for the typical “silver mirror” effect caused by oxidation, but there was frequent use of printed images on glossy paper taken from magazines and, in some cases, of texts printed on acetate. In many cases, the loss of adhesion of the Cow Gum made it possible to examine the backs and to see the initials on photographic papers, or the versions underneath the final artwork, before reapplying them with Japanese starch paste or with an adhesive based on cellulose ether in alcohol.

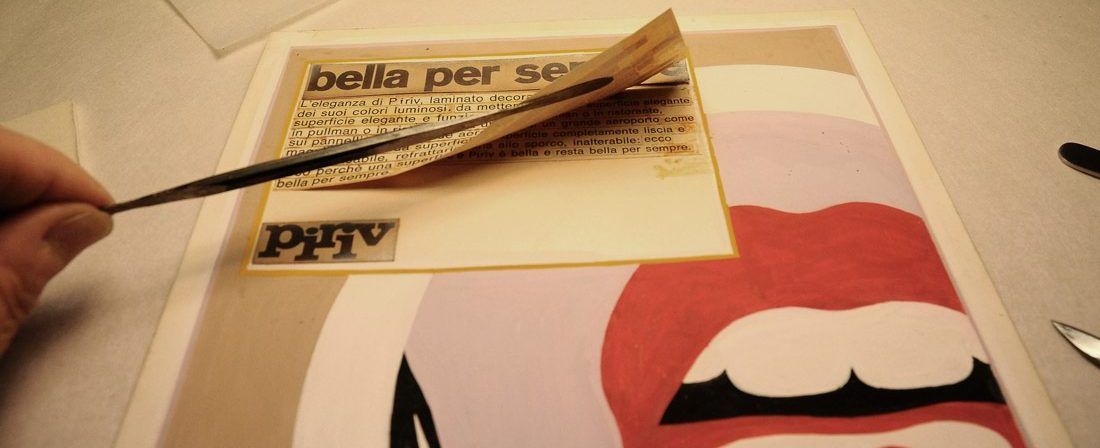

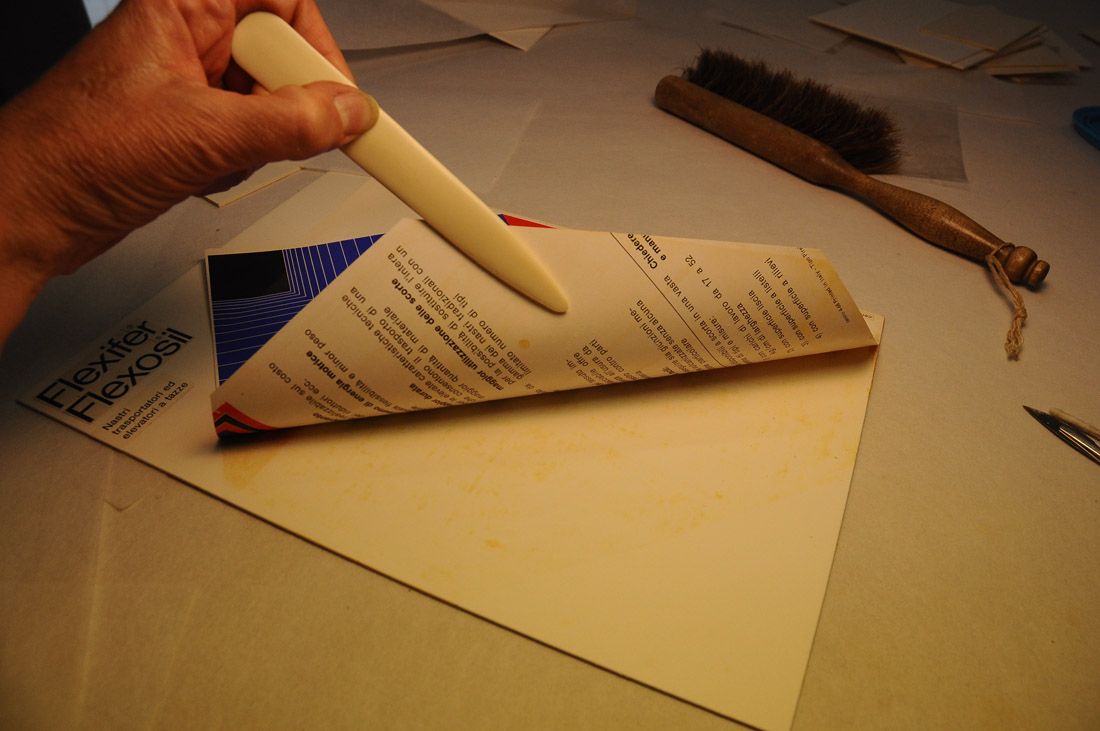

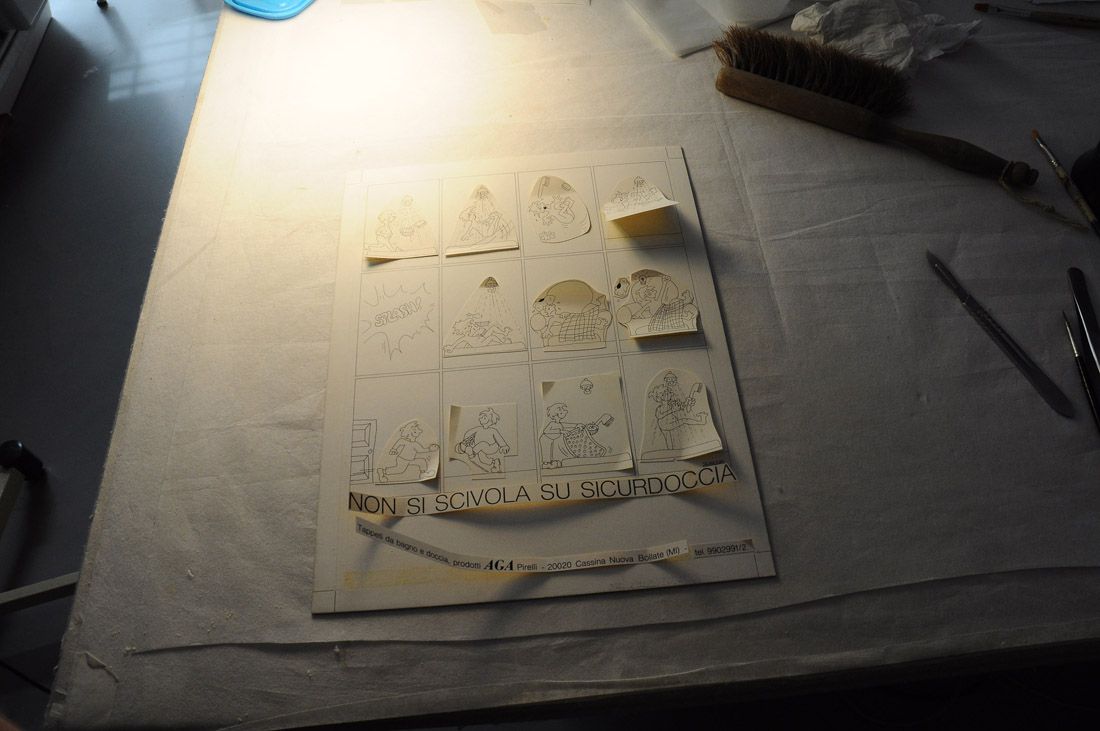

Another type of material with which I am very familiar, and which I found in many items, is that of texture screens. These are self-adhesive films, coloured or with little repeated patterns, used to fill in background areas. They were used at school in geometrical drawings to form the shadows of objects, and it was very interesting to see the superimposition of different colours in transparency. In the treated art works, adhesion had remained very good, except for minimal detachment in the corners and small areas, which was rectified with acrylic adhesive. The colours of the texture screens were not altered, thus pointing to a good degree of adhesion and to the fact that the original glue of the films is very stable and has not oxidised. One very important aspect of a fair number of cards is that of the registration marks for printing the image, which were mainly applied with little pieces of adhesive tape. As with Cow Gum, here to the glue on the tape had oxidised, darkened and lost adhesion, causing the registration marks to become detached. Fortunately, the marks left by the glue on the card made it possible to identify the original positions, so they could be repositioned correctly. Another type of element found on the various cards in a state of conservation similar to that of the registration marks is that of the colour bar, in the form of cut-outs of coloured paper used as references for printing. These were also stuck on with adhesive tape, but were no longer well attached. The same system had been used for some texts placed over previous versions. In the cases just described, it was decided, together with the head of the Historical Archive, to keep the plastic films of the adhesive tapes after removing the glue (which was the damaging part) with ether or acetone as solvents, depending on the degree of oxidation of the adhesive. The tapes were then replaced in the original positions, using an acrylic adhesive, and thus managing to maintain the visual appearance of the artwork as it was when first made. Tracing paper played an important visual and technical role, with one or more sheets (in some cases, even three) being fastened with adhesive tape on the cards. As well as being used to protect the artwork, tracing paper was also used for writing notes for the printers, as well as any variations and additions to the original artwork. The sheets of tracing paper thus bear text in pencil, in ballpoint pen (black, blue or red), and in black or red ink drawn with a Rapidograph, with felt-tip pens, Tratto pens, or coloured crayons, but there are also some of the same materials used on the cards. These include pieces of paper cut out with printed inscriptions and glued using Cow Gum, registration marks and colour samples fastened with adhesive tape or glued, and coloured transparent texture screens. The tracing paper had conservation issues that affected both the support and the materials applied onto it. The following were mainly found in the case of the supports: folds, tears, missing parts due to handling, detachment from the cardboard due to the loss of adhesion in the adhesive tapes, and also stains and residue of adhesive tape. The main problems affecting the materials applied were those already described for the papers fastened to the cards: marks caused by the Cow Gum and partial or total detachment.

Another type of material with which I am very familiar, and which I found in many items, is that of texture screens. These are self-adhesive films, coloured or with little repeated patterns, used to fill in background areas. They were used at school in geometrical drawings to form the shadows of objects, and it was very interesting to see the superimposition of different colours in transparency. In the treated art works, adhesion had remained very good, except for minimal detachment in the corners and small areas, which was rectified with acrylic adhesive. The colours of the texture screens were not altered, thus pointing to a good degree of adhesion and to the fact that the original glue of the films is very stable and has not oxidised. One very important aspect of a fair number of cards is that of the registration marks for printing the image, which were mainly applied with little pieces of adhesive tape. As with Cow Gum, here to the glue on the tape had oxidised, darkened and lost adhesion, causing the registration marks to become detached. Fortunately, the marks left by the glue on the card made it possible to identify the original positions, so they could be repositioned correctly. Another type of element found on the various cards in a state of conservation similar to that of the registration marks is that of the colour bar, in the form of cut-outs of coloured paper used as references for printing. These were also stuck on with adhesive tape, but were no longer well attached. The same system had been used for some texts placed over previous versions. In the cases just described, it was decided, together with the head of the Historical Archive, to keep the plastic films of the adhesive tapes after removing the glue (which was the damaging part) with ether or acetone as solvents, depending on the degree of oxidation of the adhesive. The tapes were then replaced in the original positions, using an acrylic adhesive, and thus managing to maintain the visual appearance of the artwork as it was when first made. Tracing paper played an important visual and technical role, with one or more sheets (in some cases, even three) being fastened with adhesive tape on the cards. As well as being used to protect the artwork, tracing paper was also used for writing notes for the printers, as well as any variations and additions to the original artwork. The sheets of tracing paper thus bear text in pencil, in ballpoint pen (black, blue or red), and in black or red ink drawn with a Rapidograph, with felt-tip pens, Tratto pens, or coloured crayons, but there are also some of the same materials used on the cards. These include pieces of paper cut out with printed inscriptions and glued using Cow Gum, registration marks and colour samples fastened with adhesive tape or glued, and coloured transparent texture screens. The tracing paper had conservation issues that affected both the support and the materials applied onto it. The following were mainly found in the case of the supports: folds, tears, missing parts due to handling, detachment from the cardboard due to the loss of adhesion in the adhesive tapes, and also stains and residue of adhesive tape. The main problems affecting the materials applied were those already described for the papers fastened to the cards: marks caused by the Cow Gum and partial or total detachment.

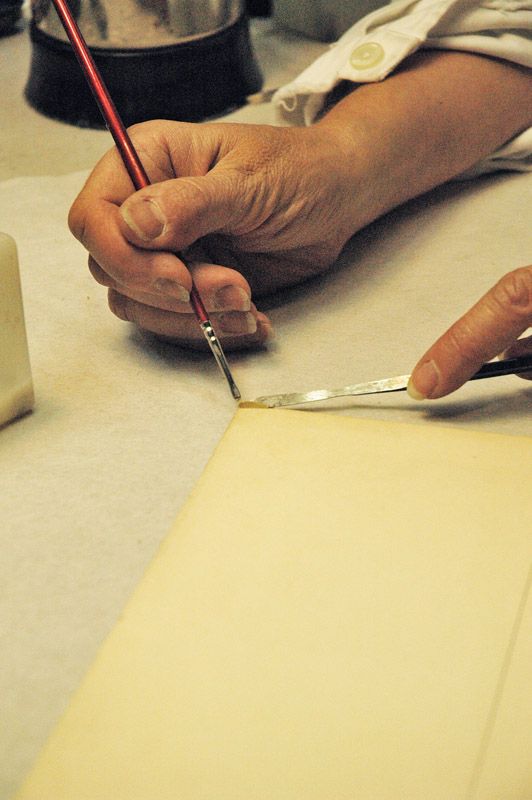

The restoration of the sheets of tracing paper first required surface cleaning, for since they are the most exposed part of the artwork, they were to a greater or lesser extent covered in dust. The remains of the adhesive tape, used to fasten the tracing paper to the card or to repair tears, were removed and cleaned with solvent. Folds and wrinkles were reduced by applying a minimum amount of humidity to the precise area, using fine retouching brushes, and the tears were mended with thin strips of very light Japanese paper on the back. Here an alcohol-based adhesive was used so as to avoid the formation of ripples, since tracing paper is very sensitive to humidity and tends to buckle permanently. Missing parts were filled in with old sheets of tracing paper that were similar in colour, attaching them with the same thin strips and adhesive as was used on the tears. Then the various papers with texts and images were fastened, either completely or partially, using the same alcohol-based glue. At the end of these operations, the sheets of tracing paper were replaced on the cards, using conservation tape. Beneath the protective paper, there were often photographic prints (corresponding to, or variants of, the photo on the artwork) or colour transparencies showing the artwork – unfortunately no longer extant – in the stages leading up to the camera-ready version, some of them made by hand using traditional techniques. The image taken from the colour transparencies was the one printed and applied to the card. The transparencies were always inserted in plastic envelopes that were not suitable for conservation, which in some cases had become stuck to the transparency itself. Sometimes the film was damaged or risked becoming so due to the presence of adhesive tapes of various kinds, which in some cases had partially unravelled and expanded over the surface leaving areas of whitish discolouring. After careful cleaning with solvent to eliminate the residue left by the old adhesive tapes on the transparencies, new conservation tapes specially designed for photographic materials and film were applied. Both the transparencies and the photographic prints were protected in conservation envelopes made of transparent polypropylene.

The criterion adopted for the operation was to consider these artworks not as end products but rather as practical instruments, for indeed they were preparatory tools for printing posters, leaflets and advertisements for magazines and publications. For the purposes of restoration, it was therefore considered essential to preserve all the traces and elements that had been added for the creation of the final print. These included notes written directly on the card or tracing paper, or on separate sheets, comments and suggested changes, and written information on the backs and fronts, as well as documentation and information about the creative work process.

Lucia Tarantola (restorer)

260 camera-ready artworks for advertisements dating from 1968 to 1981, owned by the Pirelli Historical Archive, were restored in 2016-17. The 260 items involved in the recent operation used materials and techniques typical of the period and of the sector in which they were designed and made.

In the late 1960s, the pictorial and caricatural/cartoon-style rendering of previous artists and draughtsmen began to disappear, and there was a shift to more graphic images with ample space given to text. Direct manual intervention was considerably reduced, and few artworks were made using tempera or India ink, while photographs and printed characters were used in a majority of cases. The restoration thus made it possible to go back in time through graphic studies to examine the work methods adopted before the advent of computers.

Most of the artworks in this group consist of a number of superimposed layers, with the main part of the image made on Shoeller card, which was the support most commonly used in graphic art studios, as well as in the world of contemporary art at the time. This card is about 1.5 mm thick, with an inner core consisting of several layers in wood paste, lined on the front with a very smooth, relatively non-porous, ivory-coloured coated paper and on the back with green-blue paper. In many cases, also the factory trademark, made with an embossing stamp, can be seen. Together with considerable deposits of dust (removed by surface cleaning using a Wishab sponge), the main form of damage found on the cards, caused by improper handling and conservation methods, was the presence of indentations on the edges and corners, and flaking of the constituent layers of the card. This required re-adhesion of the layers and consolidation of the edges, using Japanese starch paste between the layers of card, and mixed glue consisting of methylcellulose and an acrylic emulsion to reinforce, protect and impermeabilise the edges.

The smooth, non-absorbent coated side of the card was the one used to compose the image for the artwork: as we have seen, there were a few works in tempera and a certain number in India ink, but in most cases the images were obtained by assembling papers of various types, photographic or otherwise, with photographic or typographical prints, cut out in various shapes and glued to the card. The most evident influence of art schools can be seen in the type of adhesive used. It was not difficult to discover that most of the gluing had been done with the famous (as it certainly was back then) Cow Gum glue. This took its name not from actual cows, but from its inventor, Mr Cow. This glue had the consistency of honey and a strong smell of solvent, and it was sold in a red and white tin with the word “Cow” written conspicuously across it. It was spread with a white plastic spatula, one of which I still have today. Reading various graphics websites and talking with architects and designers, I have found that, before computers were used, all firms and studios – and not just art students – made ample use of it. The texts, images and various elements of the composition were cut out (often using the card itself as a support, and indeed many superficial cuts can be seen on the Pirelli artworks) and then glued onto the card. The advantage of Cow Gum over water-based glues was that it did not wrinkle the paper, and it also gave a certain amount of time for repositioning the various elements if one wanted to modify the composition. At the time of use, Cow Gum was transparent, but of course no one knew back then what changes it would undergo over the years. As it oxidises over time, it undergoes a change in colour, which also affects the paper it is applied to, creating brown traces where the glue was spread (particularly on the backs). It also loses its adhesive power, leading to the partial or complete detachment of the various elements stuck to the card.

This was the situation that most of the artwork involved in the restoration was in: in the past, some of the small, detached pieces were lost, but the restoration work fortunately meant it was possible to intervene in time to check the degree of adhesion and to fasten all the remaining pieces. Even just slight pressure with the tip of a scalpel was enough to detach the parts where the adhesive had become completely oxidised. This meant it was possible to recover and consolidate all the applied elements, using Japanese starch paste after mechanically eliminating the remains of the old Cow Gum that had oxidised and turned to dust. The re-adhesions were carried out completely or partially (depending on the areas where the loss of adhesion had occurred), or at least on the corners and edges, in order to avoid further loss in the future. It was not, however, possible to remove the brown stains caused by oxidation, which had become irreversible. As mentioned, many of the cut-outs glued to the cards were photographs of various types, both glossy and semi-matt, which were used both for printing images and for many of the printed texts. Limited use was made of silver-salt prints, which are recognisable for the typical “silver mirror” effect caused by oxidation, but there was frequent use of printed images on glossy paper taken from magazines and, in some cases, of texts printed on acetate. In many cases, the loss of adhesion of the Cow Gum made it possible to examine the backs and to see the initials on photographic papers, or the versions underneath the final artwork, before reapplying them with Japanese starch paste or with an adhesive based on cellulose ether in alcohol.

Another type of material with which I am very familiar, and which I found in many items, is that of texture screens. These are self-adhesive films, coloured or with little repeated patterns, used to fill in background areas. They were used at school in geometrical drawings to form the shadows of objects, and it was very interesting to see the superimposition of different colours in transparency. In the treated art works, adhesion had remained very good, except for minimal detachment in the corners and small areas, which was rectified with acrylic adhesive. The colours of the texture screens were not altered, thus pointing to a good degree of adhesion and to the fact that the original glue of the films is very stable and has not oxidised. One very important aspect of a fair number of cards is that of the registration marks for printing the image, which were mainly applied with little pieces of adhesive tape. As with Cow Gum, here to the glue on the tape had oxidised, darkened and lost adhesion, causing the registration marks to become detached. Fortunately, the marks left by the glue on the card made it possible to identify the original positions, so they could be repositioned correctly. Another type of element found on the various cards in a state of conservation similar to that of the registration marks is that of the colour bar, in the form of cut-outs of coloured paper used as references for printing. These were also stuck on with adhesive tape, but were no longer well attached. The same system had been used for some texts placed over previous versions. In the cases just described, it was decided, together with the head of the Historical Archive, to keep the plastic films of the adhesive tapes after removing the glue (which was the damaging part) with ether or acetone as solvents, depending on the degree of oxidation of the adhesive. The tapes were then replaced in the original positions, using an acrylic adhesive, and thus managing to maintain the visual appearance of the artwork as it was when first made. Tracing paper played an important visual and technical role, with one or more sheets (in some cases, even three) being fastened with adhesive tape on the cards. As well as being used to protect the artwork, tracing paper was also used for writing notes for the printers, as well as any variations and additions to the original artwork. The sheets of tracing paper thus bear text in pencil, in ballpoint pen (black, blue or red), and in black or red ink drawn with a Rapidograph, with felt-tip pens, Tratto pens, or coloured crayons, but there are also some of the same materials used on the cards. These include pieces of paper cut out with printed inscriptions and glued using Cow Gum, registration marks and colour samples fastened with adhesive tape or glued, and coloured transparent texture screens. The tracing paper had conservation issues that affected both the support and the materials applied onto it. The following were mainly found in the case of the supports: folds, tears, missing parts due to handling, detachment from the cardboard due to the loss of adhesion in the adhesive tapes, and also stains and residue of adhesive tape. The main problems affecting the materials applied were those already described for the papers fastened to the cards: marks caused by the Cow Gum and partial or total detachment.

Another type of material with which I am very familiar, and which I found in many items, is that of texture screens. These are self-adhesive films, coloured or with little repeated patterns, used to fill in background areas. They were used at school in geometrical drawings to form the shadows of objects, and it was very interesting to see the superimposition of different colours in transparency. In the treated art works, adhesion had remained very good, except for minimal detachment in the corners and small areas, which was rectified with acrylic adhesive. The colours of the texture screens were not altered, thus pointing to a good degree of adhesion and to the fact that the original glue of the films is very stable and has not oxidised. One very important aspect of a fair number of cards is that of the registration marks for printing the image, which were mainly applied with little pieces of adhesive tape. As with Cow Gum, here to the glue on the tape had oxidised, darkened and lost adhesion, causing the registration marks to become detached. Fortunately, the marks left by the glue on the card made it possible to identify the original positions, so they could be repositioned correctly. Another type of element found on the various cards in a state of conservation similar to that of the registration marks is that of the colour bar, in the form of cut-outs of coloured paper used as references for printing. These were also stuck on with adhesive tape, but were no longer well attached. The same system had been used for some texts placed over previous versions. In the cases just described, it was decided, together with the head of the Historical Archive, to keep the plastic films of the adhesive tapes after removing the glue (which was the damaging part) with ether or acetone as solvents, depending on the degree of oxidation of the adhesive. The tapes were then replaced in the original positions, using an acrylic adhesive, and thus managing to maintain the visual appearance of the artwork as it was when first made. Tracing paper played an important visual and technical role, with one or more sheets (in some cases, even three) being fastened with adhesive tape on the cards. As well as being used to protect the artwork, tracing paper was also used for writing notes for the printers, as well as any variations and additions to the original artwork. The sheets of tracing paper thus bear text in pencil, in ballpoint pen (black, blue or red), and in black or red ink drawn with a Rapidograph, with felt-tip pens, Tratto pens, or coloured crayons, but there are also some of the same materials used on the cards. These include pieces of paper cut out with printed inscriptions and glued using Cow Gum, registration marks and colour samples fastened with adhesive tape or glued, and coloured transparent texture screens. The tracing paper had conservation issues that affected both the support and the materials applied onto it. The following were mainly found in the case of the supports: folds, tears, missing parts due to handling, detachment from the cardboard due to the loss of adhesion in the adhesive tapes, and also stains and residue of adhesive tape. The main problems affecting the materials applied were those already described for the papers fastened to the cards: marks caused by the Cow Gum and partial or total detachment.

The restoration of the sheets of tracing paper first required surface cleaning, for since they are the most exposed part of the artwork, they were to a greater or lesser extent covered in dust. The remains of the adhesive tape, used to fasten the tracing paper to the card or to repair tears, were removed and cleaned with solvent. Folds and wrinkles were reduced by applying a minimum amount of humidity to the precise area, using fine retouching brushes, and the tears were mended with thin strips of very light Japanese paper on the back. Here an alcohol-based adhesive was used so as to avoid the formation of ripples, since tracing paper is very sensitive to humidity and tends to buckle permanently. Missing parts were filled in with old sheets of tracing paper that were similar in colour, attaching them with the same thin strips and adhesive as was used on the tears. Then the various papers with texts and images were fastened, either completely or partially, using the same alcohol-based glue. At the end of these operations, the sheets of tracing paper were replaced on the cards, using conservation tape. Beneath the protective paper, there were often photographic prints (corresponding to, or variants of, the photo on the artwork) or colour transparencies showing the artwork – unfortunately no longer extant – in the stages leading up to the camera-ready version, some of them made by hand using traditional techniques. The image taken from the colour transparencies was the one printed and applied to the card. The transparencies were always inserted in plastic envelopes that were not suitable for conservation, which in some cases had become stuck to the transparency itself. Sometimes the film was damaged or risked becoming so due to the presence of adhesive tapes of various kinds, which in some cases had partially unravelled and expanded over the surface leaving areas of whitish discolouring. After careful cleaning with solvent to eliminate the residue left by the old adhesive tapes on the transparencies, new conservation tapes specially designed for photographic materials and film were applied. Both the transparencies and the photographic prints were protected in conservation envelopes made of transparent polypropylene.

The criterion adopted for the operation was to consider these artworks not as end products but rather as practical instruments, for indeed they were preparatory tools for printing posters, leaflets and advertisements for magazines and publications. For the purposes of restoration, it was therefore considered essential to preserve all the traces and elements that had been added for the creation of the final print. These included notes written directly on the card or tracing paper, or on separate sheets, comments and suggested changes, and written information on the backs and fronts, as well as documentation and information about the creative work process.

Lucia Tarantola (restorer)