‘Words that give life’: teacher, kindness, respect, balance and integrity

There are words that give life. In his poem, Paul Éluard — one of the most intense French poets of the 20th century — listed them as follows: ‘The word warmth the word trust/ love justice and the word freedom/ the word child and the word kindness/ the word courage/ and the word discover/ the word brother and the word comrade…’. ‘Innocent words,’ he called them, also to recall ‘certain country names of villages and certain names of women and of friends.’ Like Gabriel Péri, a hero of the Resistance, to whom the poem was dedicated.

We can try to continue this list today as a kind of antidote to the difficult times we are living through. A time of violence, vulgarity, narcissism and politics ‘full of nightmares and short on dreams’ (Il Foglio, 6 September), of lies and deceit, which makes it increasingly difficult to write stories that reflect humanity.

Let’s list the word teacher, for example. And the word integrity. The word work, the word respect and the word balance. The word thanks and the word sorry. The word others. And, after Eluard, we could reimagine the word justice and the word kindness.

The reference examples in our discussion are taken from newspaper articles. This shows that reading well-written and edited newspapers provides news, insights and cultural references that offer hope, despite the insults and contempt directed at journalists by serial haters on social media and high-profile politicians. One could say Minima Moralia, a deference to, and a respectful nod to, much more illustrious precedents, without any pretension of comparison.

A person is defined by the adventures they have had, the happiness and pain they have experienced, the books they have read, the people they have loved, their friends and their teachers.

Let’s take a moment to reflect on the word ‘teacher’ (without, however, inappropriately attributing it to too many people). One of the tools we use is the new book by Massimo Recalcati, published ten years after the captivating The Hour of Lesson: it is The Light and the Wave, published by Einaudi, with the essential subtitle What does it mean to teach? The word for teacher in Italian is maestro and comes from the Latin magis, which means ‘more’. More knowledge to acquire, more questions to ask, more answers to seek, more points of view to consider. This is not nihilistic relativism. Rather, it is an attitude that transmits knowledge as a critical ability and a habit of viewing the world through ‘the eyes of others’.

In his book, Recalcati discusses 20th-century teachers such as Jacques Lacan, Gilles Deleuze, and Pier Paolo Pasolini. And each of us could write our own additional list. Among ‘the just who are saving the world’, Jorge Luis Borges counts ‘a man who cultivates his garden as Voltaire wanted’ and ‘those who discover an etymology with pleasure’. Someone attentive to Sicilian culture, and thus to the world, would point to Pirandello, Vittorini, Sciascia and Camilleri, the latter of whom is the subject of much discussion this year, marking the centenary of his birth. In Milan, it is worth rereading Manzoni and Testori, as well as Gadda. And remembering the irony of Alberto Arbasino, as discussed by Edmondo Berselli: ‘In Italy, there is a magical moment when one transitions from the category of beautiful promise to that of being the usual jerk. Only a few lucky ones are then granted the age to access the dignity of being a revered teacher’.

Few lucky and capable ones, indeed. Giuliano Ferrara is absolutely right in his reflection on the excessive number of pages dedicated to memories and praise for recently deceased illustrious figures and celebrities: ‘Exaggerating tires even the memory’ (Il Foglio, 6 September). Beauty, style, and elegance (here are other words to emphasise) are the result of a sober and sophisticated sense of measure.

Teachers in the heights of the great culture. And teachers are fundamental in life and in daily school.

My paternal grandmother Lucia was a teacher who taught hundreds of children to read and do arithmetic in Caronia, a Norman village on the Tyrrhenian coast of Sicily, at the turn of the twentieth century. Over time, I discovered that many had fond memories of her. She taught them how to learn, how to understand words and numbers, and how to understand the world. She helped them to become people, as teachers do today and will do again tomorrow. Recalcati asserts: ‘it is only through contagion with the teacher’s desire that the student’s desire is produced, and that the teacher’s task is to ignite the desire to know.’

There is another key word that is linked to the teacher, thinking about the lives of others and that is respect. Once again, Sergio Mattarella, the President of the Republic, emphasised that ‘only in a world founded on respect can progress be achieved’. In a message to the European House Ambrosetti Forum in Cernobbio (Corriere della Sera, 7 September), he urged Europe to ‘rebuild the centrality of international law’ and ‘not yield to autocratic regimes’, also criticising ‘the overwhelming weight of global corporations’, particularly Big Tech. ‘They are the new East India Companies.’ , Human respect, against the arrogant technocracies. Respect for rules and values. Respect for a better economic and social balance.

And here is another essential word: balance. What does it mean to seek new dimensions of compatibility between economic growth and social justice, productivity and sustainability, and competitiveness and solidarity? According to the principles of a ‘reformist enterprise’, this can be a driving force for a new and better era of development, not just growth. Economic and civil progress should be measured not only by GDP (gross domestic product, or the wealth created), but also by BES (fair and sustainable well-being), an authoritative indicator developed by Istat years ago. It should also be measured by the HDI (human development index, introduced by the UN in the 1990s to measure well-being and quality of life). This index considers not only income, but also health and education. The Knowledge Economic Index was developed by the World Bank Institute to assess a country’s position in the global knowledge economy. This is because the dissemination of knowledge, and thus critical thinking, is closely linked to freedom, responsibility and the quality of development.

A fundamental theory to consider is that developed by Martha Nussbaum on the idea of the Capability Approach, which evaluates well-being and quality of life in terms of the real opportunities a person has to live a life they desire and consider worthy of living. And here is another ‘word that gives life’: dignity.

All this, to focus on just one of many examples, means taking responsibility on the part of politics and the ruling classes in general for responding to the 1.4 million young people aged 15 to 24 who are ‘NEET’ (not in education, employment or training). This represents a significant amount of ‘wasted human capital’ (Chiara Saraceno, La Stampa, 6 September), which indicates dramatic personal and social distress and creates unacceptable imbalances in the country’s structure. This is the exact opposite of the inclusivity on which a solid democracy is based, as well as of personal and social dignity.

Laura Linda Sabbadini is therefore right to argue in her new book The Country That Matters (Marsilio) that we must reason based on data and facts, not factoids, post-truth and convenient statistics. Measuring inequalities also contributes to saving democracy.

Regarding balance, it might be worth providing another small but significant example on the relationship between life and work. It is worth noting that one of Milan’s most famous trattorias, Trippa in Porta Romana, has decided to close on Saturdays and Sundays. It is so successful that one has to wait months for a reservation thanks to the good food. ‘Less money, but happier and a better life,’ says Pietro Caroli, the founder, alongside chef Diego Rossi (Corriere della Sera, 4 September). In frantic, glittering Milan, prioritising quality of life and work over making money is indicative of a minority trend that must be embraced and valued.

Another word that can be linked to the idea of a fair and sustainable economy is probity. Marco Tronchetti Provera, the CEO of Pirelli, used it to commemorate Leopoldo Pirelli on the centenary of his birth: ‘An entrepreneur, one of the most visionary of his generation. A decent man, as one would have said in the past; sensitive to social and cultural issues, and endowed with a great sense of responsibility towards the company he led and the country’s institutions’ (Corriere della Sera, 25 August). ‘An Enlightenment thinker in business; it is ethics that support the mission of an entrepreneur’.

In the difficult and competitive world of the market economy, values and passions are all the more important. In this period of innovation, work and profitability, it is all the more important to be able to speak of a better future.

The ethics of doing and of doing things well have been discussed recently in relation to Giorgio Armani, a prominent figure in the worlds of fashion and culture who has just passed away. This links the moral dimension to an idea that goes beyond fashion and encompasses the deepest sense of elegance as a style of work and life that includes moderation, good taste and kindness. Here we are again with words ‘that give life’.

These are indeed challenging words, all of which we are reflecting on. Last utopias, as some might say. And rightly so. Yet, in times of swift and heavy change, it is necessary to insist on the fertile words of good feelings and behaviours. This conviction is strengthened by the comfort of classic, wise and severe pages. Take Lewis Mumford, for example, who invites us to distinguish ‘the utopia of escape’ (fantasy, building castles in the air) from the ‘utopia of reconstruction’ (trying to make the world a little better — a topic we have already discussed on this blog).

Or those with which Italo Calvino concludes Invisible Cities, inviting us to ‘seek and recognise, who and what, amidst hell, is not hell, and make it last, and give it space’.

Therefore, it is worth continuing the list of ‘words that give life’, Eluard’s ‘innocent words’. Each of us in our own way.

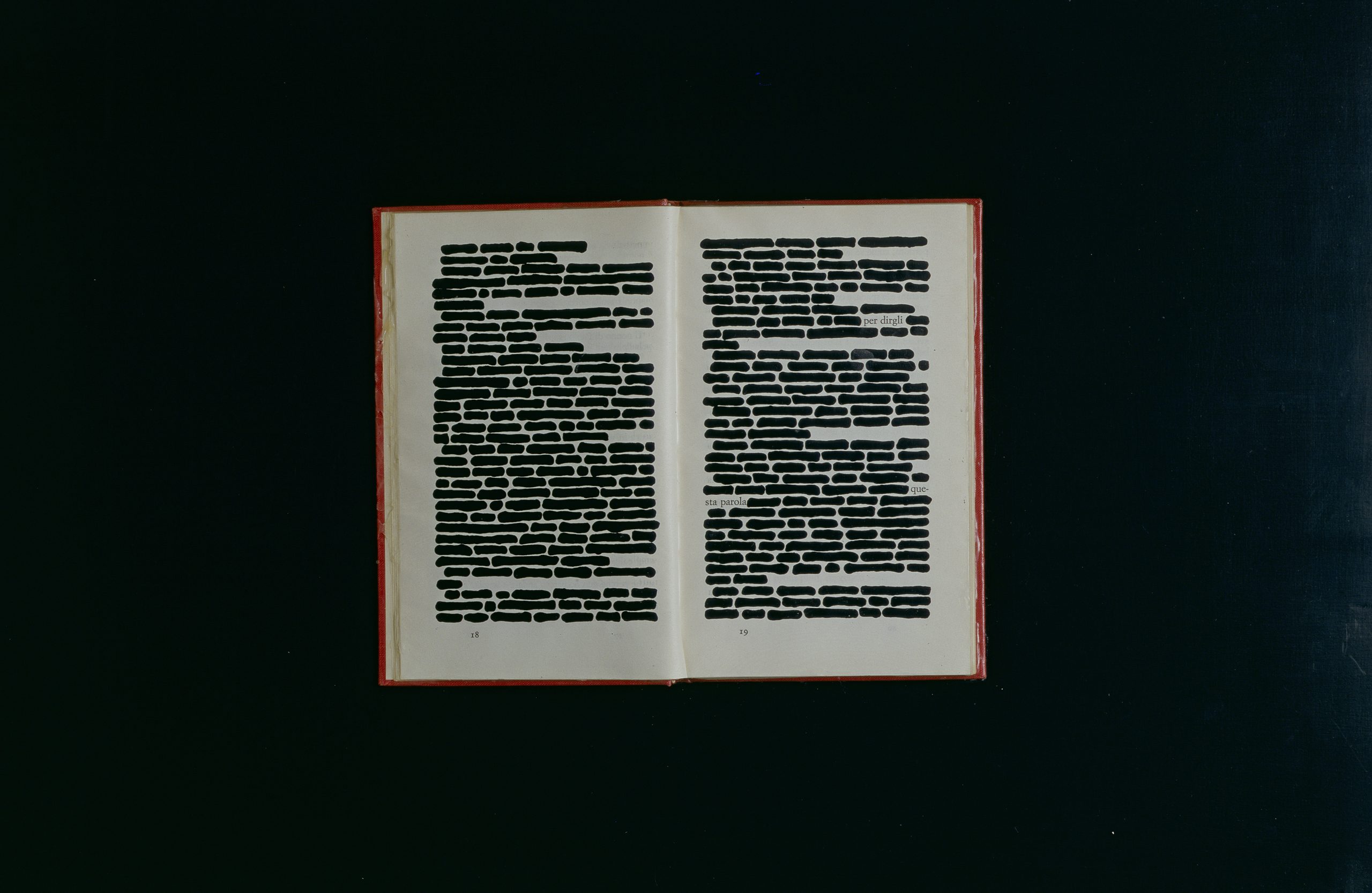

Emilio Isgrò, Libro cancellato, 1964, Museo del Novecento, Milan

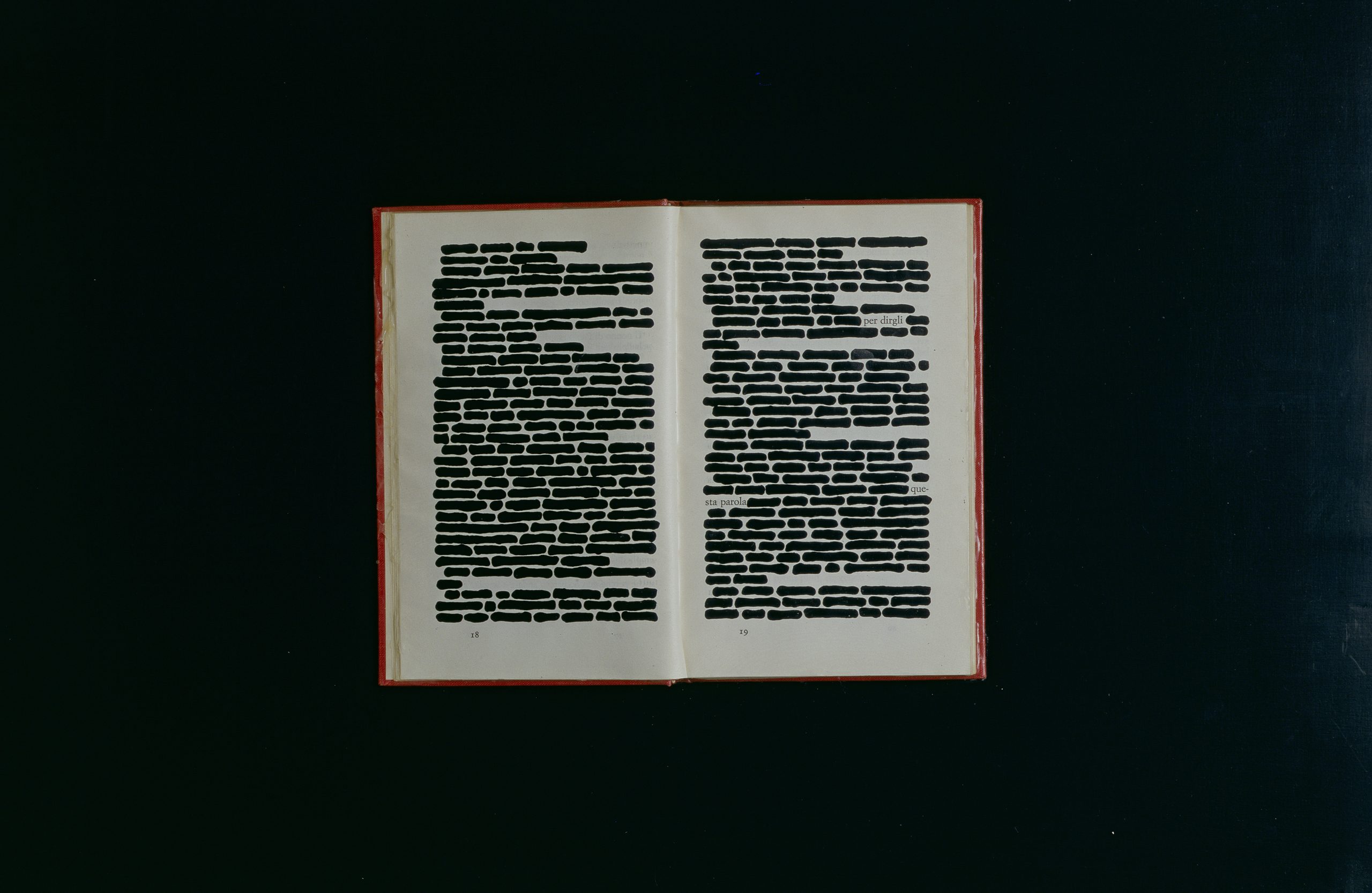

Getty Images

There are words that give life. In his poem, Paul Éluard — one of the most intense French poets of the 20th century — listed them as follows: ‘The word warmth the word trust/ love justice and the word freedom/ the word child and the word kindness/ the word courage/ and the word discover/ the word brother and the word comrade…’. ‘Innocent words,’ he called them, also to recall ‘certain country names of villages and certain names of women and of friends.’ Like Gabriel Péri, a hero of the Resistance, to whom the poem was dedicated.

We can try to continue this list today as a kind of antidote to the difficult times we are living through. A time of violence, vulgarity, narcissism and politics ‘full of nightmares and short on dreams’ (Il Foglio, 6 September), of lies and deceit, which makes it increasingly difficult to write stories that reflect humanity.

Let’s list the word teacher, for example. And the word integrity. The word work, the word respect and the word balance. The word thanks and the word sorry. The word others. And, after Eluard, we could reimagine the word justice and the word kindness.

The reference examples in our discussion are taken from newspaper articles. This shows that reading well-written and edited newspapers provides news, insights and cultural references that offer hope, despite the insults and contempt directed at journalists by serial haters on social media and high-profile politicians. One could say Minima Moralia, a deference to, and a respectful nod to, much more illustrious precedents, without any pretension of comparison.

A person is defined by the adventures they have had, the happiness and pain they have experienced, the books they have read, the people they have loved, their friends and their teachers.

Let’s take a moment to reflect on the word ‘teacher’ (without, however, inappropriately attributing it to too many people). One of the tools we use is the new book by Massimo Recalcati, published ten years after the captivating The Hour of Lesson: it is The Light and the Wave, published by Einaudi, with the essential subtitle What does it mean to teach? The word for teacher in Italian is maestro and comes from the Latin magis, which means ‘more’. More knowledge to acquire, more questions to ask, more answers to seek, more points of view to consider. This is not nihilistic relativism. Rather, it is an attitude that transmits knowledge as a critical ability and a habit of viewing the world through ‘the eyes of others’.

In his book, Recalcati discusses 20th-century teachers such as Jacques Lacan, Gilles Deleuze, and Pier Paolo Pasolini. And each of us could write our own additional list. Among ‘the just who are saving the world’, Jorge Luis Borges counts ‘a man who cultivates his garden as Voltaire wanted’ and ‘those who discover an etymology with pleasure’. Someone attentive to Sicilian culture, and thus to the world, would point to Pirandello, Vittorini, Sciascia and Camilleri, the latter of whom is the subject of much discussion this year, marking the centenary of his birth. In Milan, it is worth rereading Manzoni and Testori, as well as Gadda. And remembering the irony of Alberto Arbasino, as discussed by Edmondo Berselli: ‘In Italy, there is a magical moment when one transitions from the category of beautiful promise to that of being the usual jerk. Only a few lucky ones are then granted the age to access the dignity of being a revered teacher’.

Few lucky and capable ones, indeed. Giuliano Ferrara is absolutely right in his reflection on the excessive number of pages dedicated to memories and praise for recently deceased illustrious figures and celebrities: ‘Exaggerating tires even the memory’ (Il Foglio, 6 September). Beauty, style, and elegance (here are other words to emphasise) are the result of a sober and sophisticated sense of measure.

Teachers in the heights of the great culture. And teachers are fundamental in life and in daily school.

My paternal grandmother Lucia was a teacher who taught hundreds of children to read and do arithmetic in Caronia, a Norman village on the Tyrrhenian coast of Sicily, at the turn of the twentieth century. Over time, I discovered that many had fond memories of her. She taught them how to learn, how to understand words and numbers, and how to understand the world. She helped them to become people, as teachers do today and will do again tomorrow. Recalcati asserts: ‘it is only through contagion with the teacher’s desire that the student’s desire is produced, and that the teacher’s task is to ignite the desire to know.’

There is another key word that is linked to the teacher, thinking about the lives of others and that is respect. Once again, Sergio Mattarella, the President of the Republic, emphasised that ‘only in a world founded on respect can progress be achieved’. In a message to the European House Ambrosetti Forum in Cernobbio (Corriere della Sera, 7 September), he urged Europe to ‘rebuild the centrality of international law’ and ‘not yield to autocratic regimes’, also criticising ‘the overwhelming weight of global corporations’, particularly Big Tech. ‘They are the new East India Companies.’ , Human respect, against the arrogant technocracies. Respect for rules and values. Respect for a better economic and social balance.

And here is another essential word: balance. What does it mean to seek new dimensions of compatibility between economic growth and social justice, productivity and sustainability, and competitiveness and solidarity? According to the principles of a ‘reformist enterprise’, this can be a driving force for a new and better era of development, not just growth. Economic and civil progress should be measured not only by GDP (gross domestic product, or the wealth created), but also by BES (fair and sustainable well-being), an authoritative indicator developed by Istat years ago. It should also be measured by the HDI (human development index, introduced by the UN in the 1990s to measure well-being and quality of life). This index considers not only income, but also health and education. The Knowledge Economic Index was developed by the World Bank Institute to assess a country’s position in the global knowledge economy. This is because the dissemination of knowledge, and thus critical thinking, is closely linked to freedom, responsibility and the quality of development.

A fundamental theory to consider is that developed by Martha Nussbaum on the idea of the Capability Approach, which evaluates well-being and quality of life in terms of the real opportunities a person has to live a life they desire and consider worthy of living. And here is another ‘word that gives life’: dignity.

All this, to focus on just one of many examples, means taking responsibility on the part of politics and the ruling classes in general for responding to the 1.4 million young people aged 15 to 24 who are ‘NEET’ (not in education, employment or training). This represents a significant amount of ‘wasted human capital’ (Chiara Saraceno, La Stampa, 6 September), which indicates dramatic personal and social distress and creates unacceptable imbalances in the country’s structure. This is the exact opposite of the inclusivity on which a solid democracy is based, as well as of personal and social dignity.

Laura Linda Sabbadini is therefore right to argue in her new book The Country That Matters (Marsilio) that we must reason based on data and facts, not factoids, post-truth and convenient statistics. Measuring inequalities also contributes to saving democracy.

Regarding balance, it might be worth providing another small but significant example on the relationship between life and work. It is worth noting that one of Milan’s most famous trattorias, Trippa in Porta Romana, has decided to close on Saturdays and Sundays. It is so successful that one has to wait months for a reservation thanks to the good food. ‘Less money, but happier and a better life,’ says Pietro Caroli, the founder, alongside chef Diego Rossi (Corriere della Sera, 4 September). In frantic, glittering Milan, prioritising quality of life and work over making money is indicative of a minority trend that must be embraced and valued.

Another word that can be linked to the idea of a fair and sustainable economy is probity. Marco Tronchetti Provera, the CEO of Pirelli, used it to commemorate Leopoldo Pirelli on the centenary of his birth: ‘An entrepreneur, one of the most visionary of his generation. A decent man, as one would have said in the past; sensitive to social and cultural issues, and endowed with a great sense of responsibility towards the company he led and the country’s institutions’ (Corriere della Sera, 25 August). ‘An Enlightenment thinker in business; it is ethics that support the mission of an entrepreneur’.

In the difficult and competitive world of the market economy, values and passions are all the more important. In this period of innovation, work and profitability, it is all the more important to be able to speak of a better future.

The ethics of doing and of doing things well have been discussed recently in relation to Giorgio Armani, a prominent figure in the worlds of fashion and culture who has just passed away. This links the moral dimension to an idea that goes beyond fashion and encompasses the deepest sense of elegance as a style of work and life that includes moderation, good taste and kindness. Here we are again with words ‘that give life’.

These are indeed challenging words, all of which we are reflecting on. Last utopias, as some might say. And rightly so. Yet, in times of swift and heavy change, it is necessary to insist on the fertile words of good feelings and behaviours. This conviction is strengthened by the comfort of classic, wise and severe pages. Take Lewis Mumford, for example, who invites us to distinguish ‘the utopia of escape’ (fantasy, building castles in the air) from the ‘utopia of reconstruction’ (trying to make the world a little better — a topic we have already discussed on this blog).

Or those with which Italo Calvino concludes Invisible Cities, inviting us to ‘seek and recognise, who and what, amidst hell, is not hell, and make it last, and give it space’.

Therefore, it is worth continuing the list of ‘words that give life’, Eluard’s ‘innocent words’. Each of us in our own way.

Emilio Isgrò, Libro cancellato, 1964, Museo del Novecento, Milan

Getty Images