New Materials, Inventions, and Patents

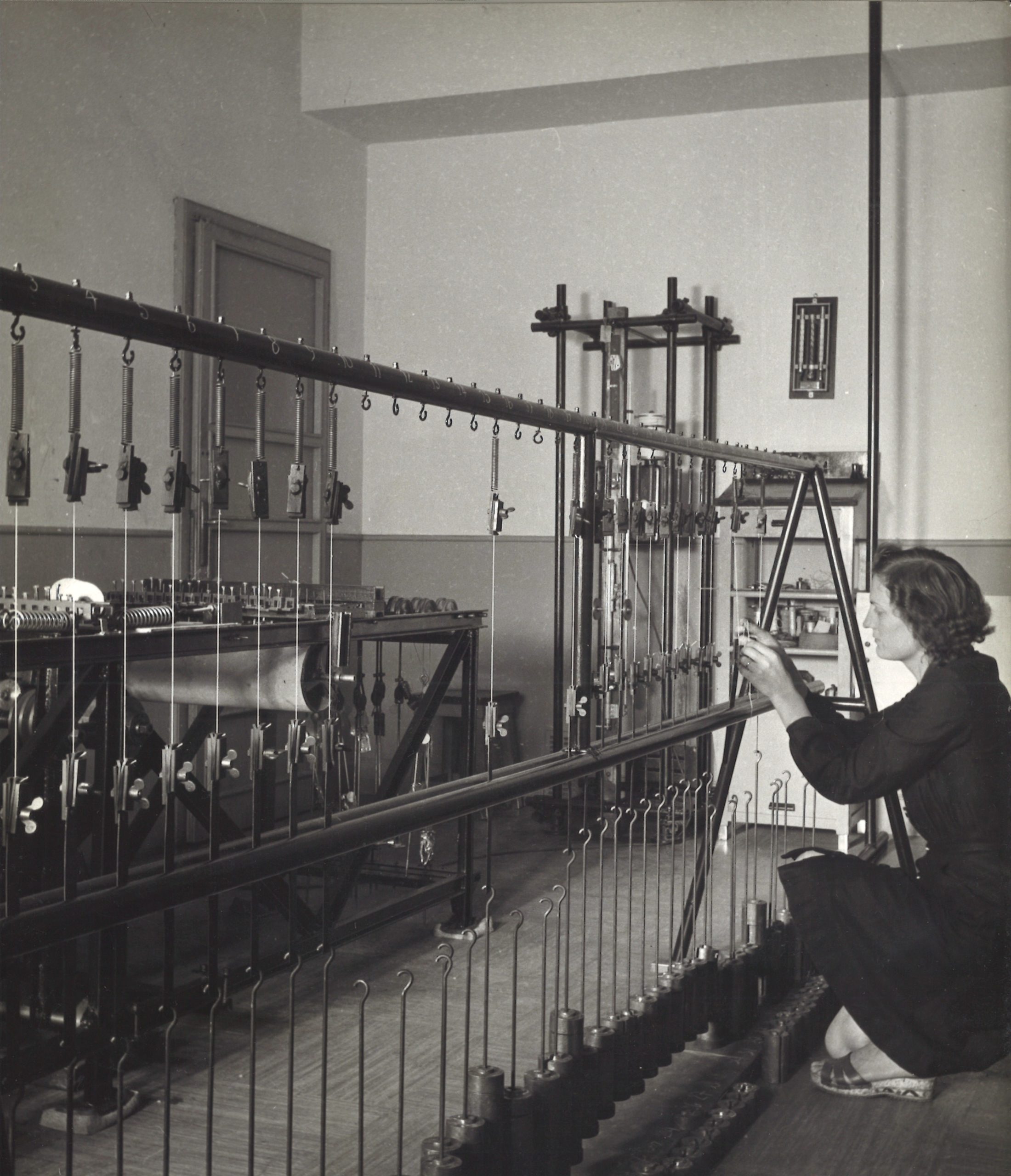

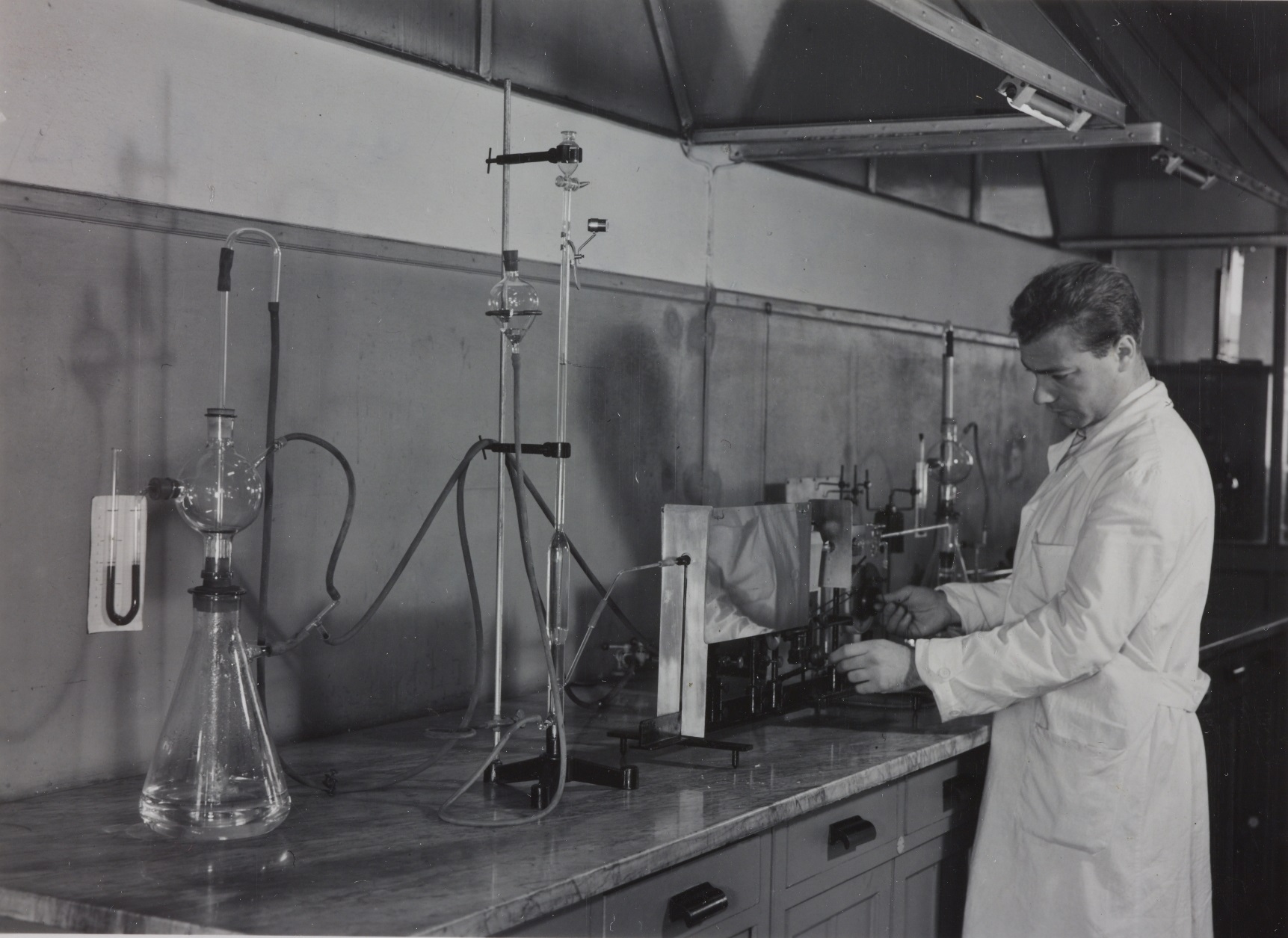

In 1937, Giulio Natta—then full professor at the Politecnico University of Turin—was commissioned by Pirelli to find an alternative to importing natural rubber from plantations in South America and the Far East, which was becoming increasingly difficult. Thanks to the work of the future Nobel laureate, the laboratories at Bicocca came up with an original technology for producing synthetic rubber and in 1938 two patents were filed for the separation of butylene and butadiene. Among the thousands of test specifications produced by the Tyre Research and Development department, the word “cauccital” – a blend of “caucciu” (rubber) and “Italy” – appears for the first time, marking the beginning of experiments with the laboratory-produced rubber now commonly used across the entire industry. It was the start of a technological revolution. Alongside these specifications, now held in our Historical Archive, there are technical data sheets detailing mould dimensions for tyre vulcanisation, tread designs, and the original markings (sizes, tyre type, company logo) embossed on the sidewall. These documents have accompanied the development and evolution of all Pirelli tyres, every step of the way, ever since the early 1930s, from memorable products such as the Stella Bianca and Cinturato, to the Corsa racing versions, through to the experimentation with Cord fabrics. The 1930s and 1940s also provide the first photographic evidence of the people who worked in these experimentation laboratories. Together with the technicians and researchers, the scientific community and its instruments take centre stage: the work benches of the chemical and physics laboratories have microscopes, ampoules, slides, test tubes, torque transducers and plastometers, shown close up to highlight the details.

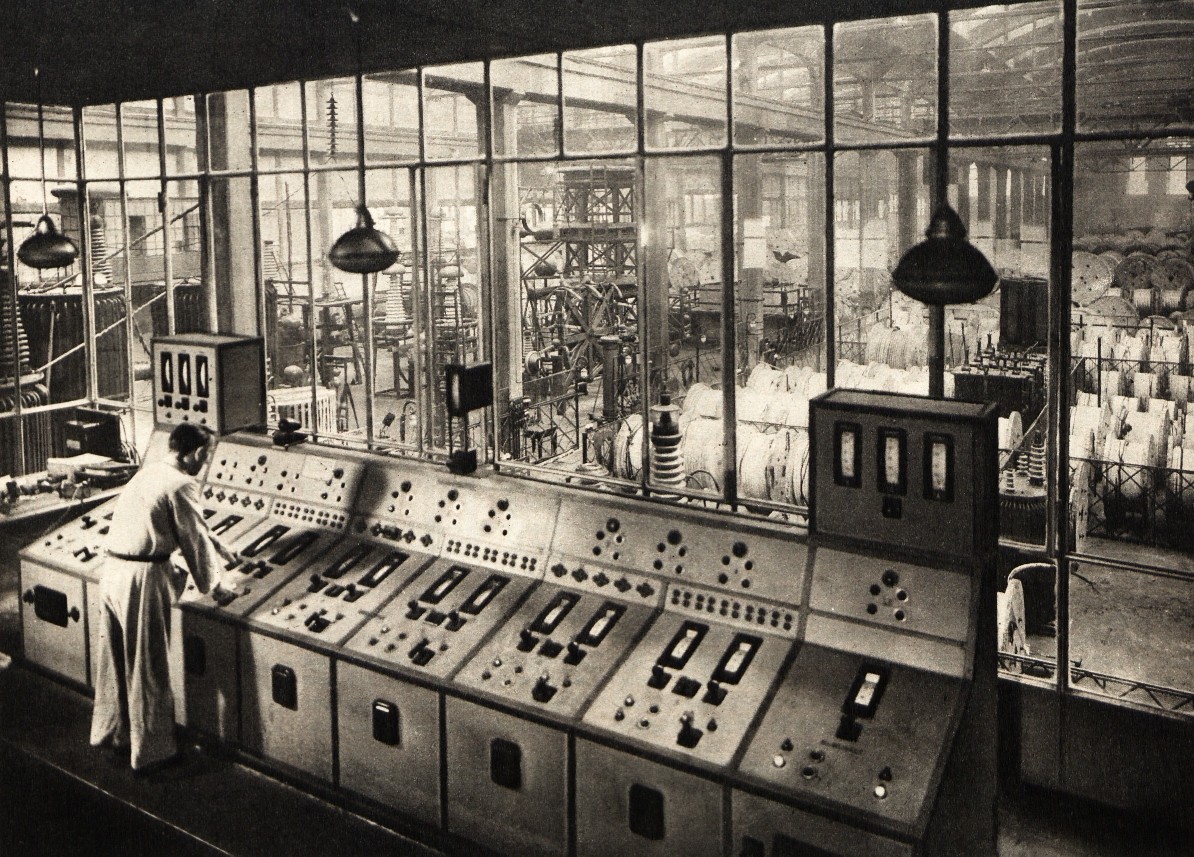

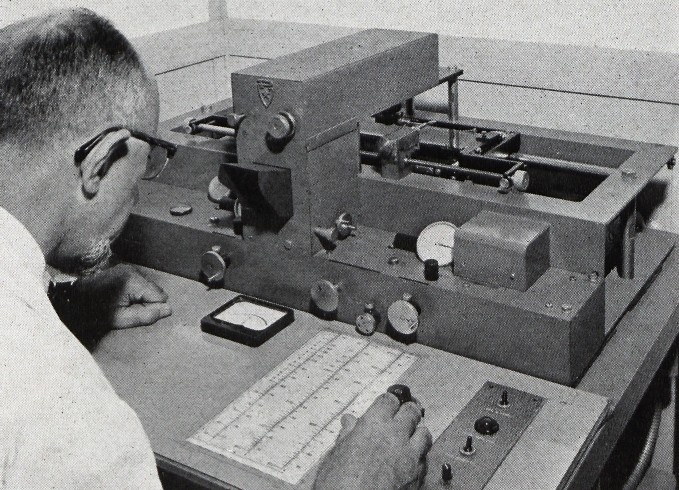

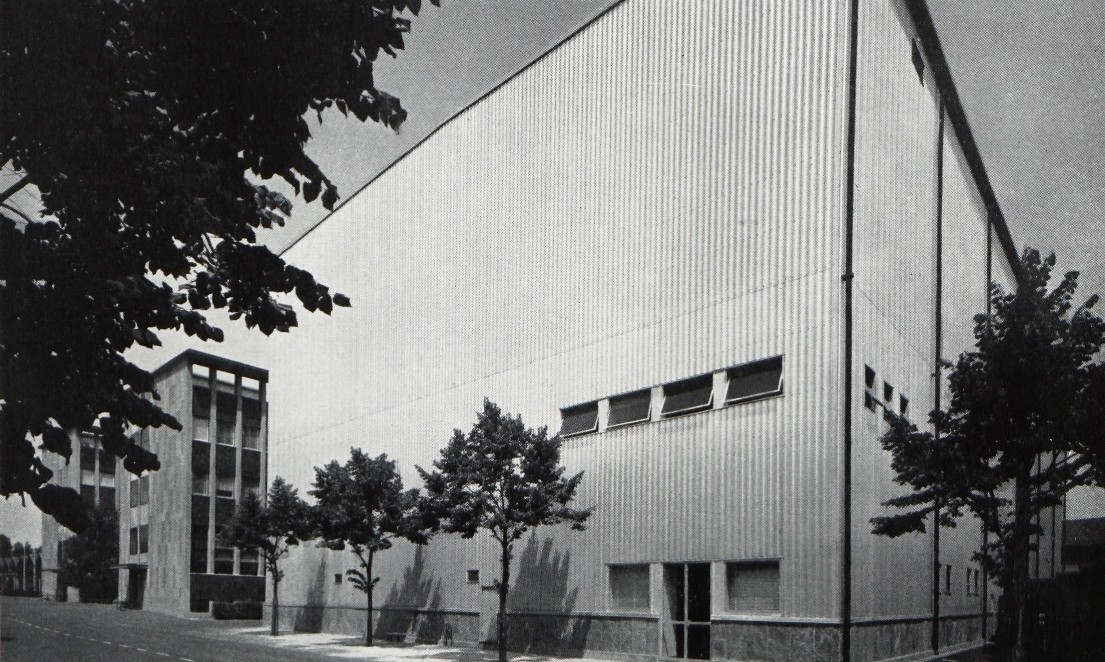

In the immediate post-war years, Pirelli oversaw the creation of a technological centre with vast laboratories specialising in various branches of chemistry and physics. The 1957 annual report notes: “in the field of technical progress, new research laboratories began operation in Bicocca and have proved to be a model of efficiency with state-of-the-art equipment. In particular, these laboratories are equipped with an electron accelerator generator of two mega electron volts, to be used primarily for research on rubber and plastics.” During the 1950s, renowned photographers such as Aldo Ballo, were invited to capture the complexities of these research facilities at Pirelli. Organised and named according to the branch of activity and the site of experiments and tests in the run-up to the manufacture of the company’s products, these laboratories embodied science as both study and application, as we see in their photographs. In 1960, Pirelli magazine wrote about the purchase and installation of two new pieces of equipment – a microphotometer and an optical comparator – both designed by Pirelli personnel. In 1963 came the opening of a new laboratory for the electrical sector, described as “one of the largest currently existing in the world for very high voltage tests”.

In 1937, Giulio Natta—then full professor at the Politecnico University of Turin—was commissioned by Pirelli to find an alternative to importing natural rubber from plantations in South America and the Far East, which was becoming increasingly difficult. Thanks to the work of the future Nobel laureate, the laboratories at Bicocca came up with an original technology for producing synthetic rubber and in 1938 two patents were filed for the separation of butylene and butadiene. Among the thousands of test specifications produced by the Tyre Research and Development department, the word “cauccital” – a blend of “caucciu” (rubber) and “Italy” – appears for the first time, marking the beginning of experiments with the laboratory-produced rubber now commonly used across the entire industry. It was the start of a technological revolution. Alongside these specifications, now held in our Historical Archive, there are technical data sheets detailing mould dimensions for tyre vulcanisation, tread designs, and the original markings (sizes, tyre type, company logo) embossed on the sidewall. These documents have accompanied the development and evolution of all Pirelli tyres, every step of the way, ever since the early 1930s, from memorable products such as the Stella Bianca and Cinturato, to the Corsa racing versions, through to the experimentation with Cord fabrics. The 1930s and 1940s also provide the first photographic evidence of the people who worked in these experimentation laboratories. Together with the technicians and researchers, the scientific community and its instruments take centre stage: the work benches of the chemical and physics laboratories have microscopes, ampoules, slides, test tubes, torque transducers and plastometers, shown close up to highlight the details.

In the immediate post-war years, Pirelli oversaw the creation of a technological centre with vast laboratories specialising in various branches of chemistry and physics. The 1957 annual report notes: “in the field of technical progress, new research laboratories began operation in Bicocca and have proved to be a model of efficiency with state-of-the-art equipment. In particular, these laboratories are equipped with an electron accelerator generator of two mega electron volts, to be used primarily for research on rubber and plastics.” During the 1950s, renowned photographers such as Aldo Ballo, were invited to capture the complexities of these research facilities at Pirelli. Organised and named according to the branch of activity and the site of experiments and tests in the run-up to the manufacture of the company’s products, these laboratories embodied science as both study and application, as we see in their photographs. In 1960, Pirelli magazine wrote about the purchase and installation of two new pieces of equipment – a microphotometer and an optical comparator – both designed by Pirelli personnel. In 1963 came the opening of a new laboratory for the electrical sector, described as “one of the largest currently existing in the world for very high voltage tests”.