Three Winter Tales

Pirelli and its winter products have inspired successful and memorable communication campaigns, thanks to an effective blend of technical content and value-driven messages. Together, they have shaped an innovative and engaging narrative: the allure of a season defined by comfort, safety, and pleasure

“Why do these artists forget the snow and the mountains? The skis? The icicles hanging from the roofs?” At first glance, Bob Noorda‘s stylised drawing for the advertising campaign for the Inverno tyre raised some doubts. We know this from a handwritten note on the back of the sketch entitled “per l’inverno il pneumatico inverno” (the idea being: “For winter: the Winter tyre”) preserved in our Historical Archive and catalogued as “tempera and collage on card with acetate sheet, with lettering”. The work dates from 1954 and is among the first commissions Pirelli entrusted to the young Dutch-born graphic designer. It was created to promote Pirelli’s first winter tyre, the Inverno, launched in 1951 and distinguished by its herringbone tread pattern. The author of the note, whose identity remains unknown, would clearly have wanted more realistic elements, like those that appeared in the advertisements designed by Ezio Bonini in the same years. Noorda had only recently arrived in Milan and was part of a community of graphic artists and designers who approached advertising as a design discipline. Their aim was clear, instant communication, achieved through the recognisability of the graphic element.

In this sketch too, Noorda eliminates everything superfluous. Yet his essential style is by no means pure abstraction. The impeccably clean lines of the decidedly wintry tree echo the herringbone tread, conveying with striking clarity the tyre’s defining technological feature.

Pirelli would go on to commission a remarkable number of works from Noorda and appoint him as art director in 1961. The relationship between the Milanese company and the Dutch designer quickly evolved increasingly reflecting Pirelli’s values, including in communication: an embrace of innovation.

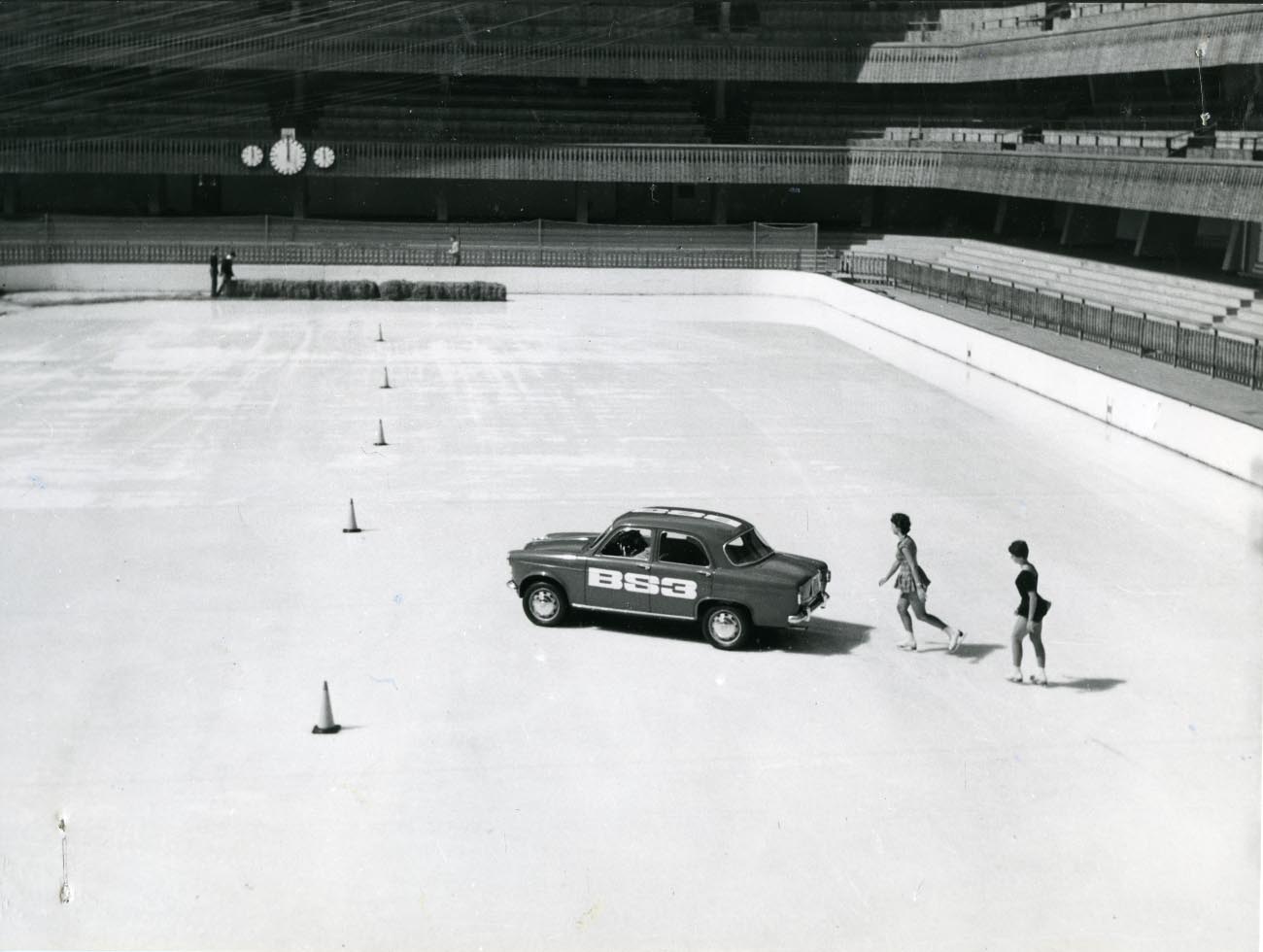

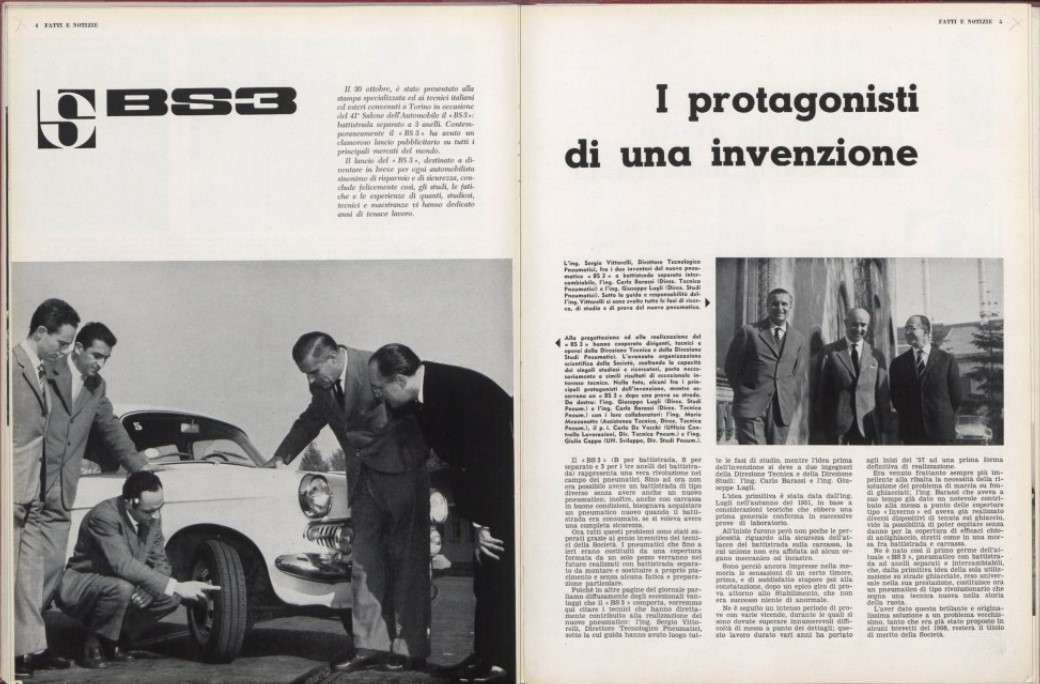

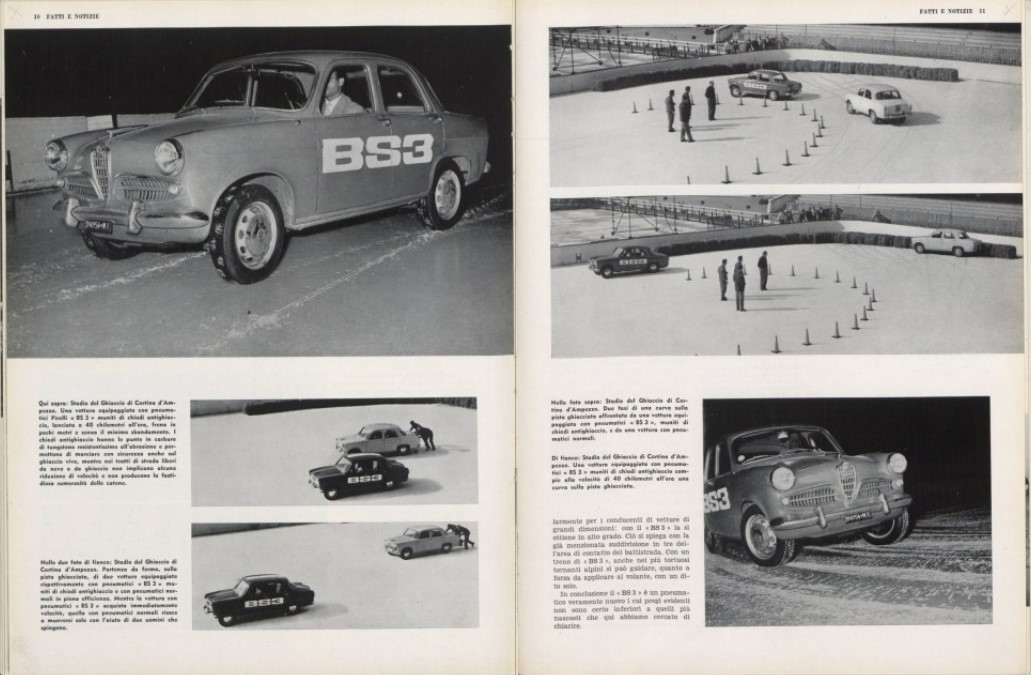

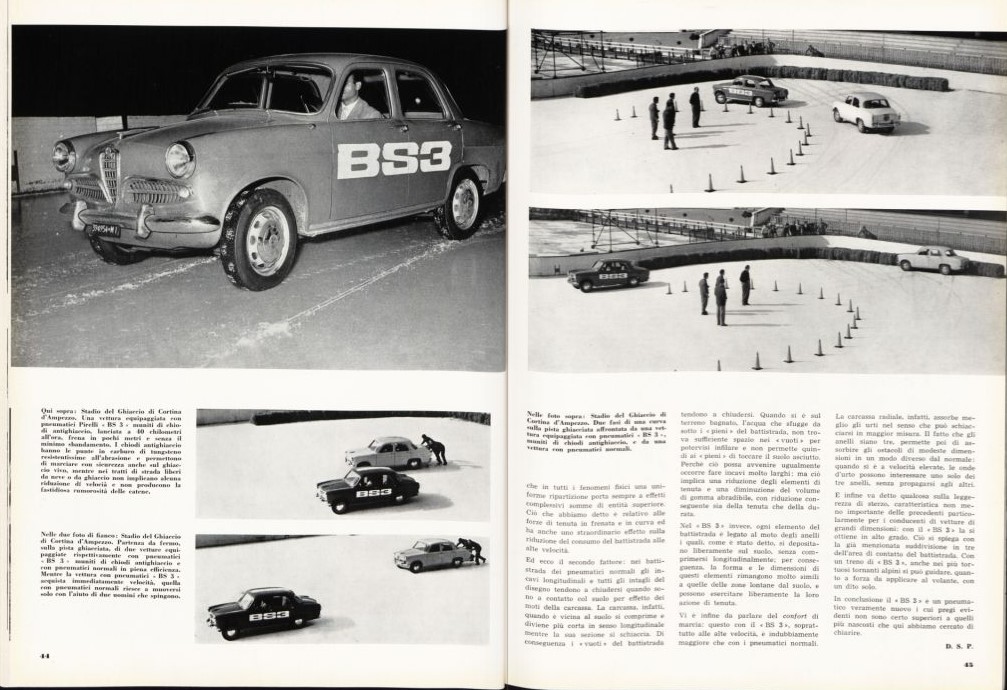

In the autumn of 1959, the launch of the Pirelli BS3 was an international event. A press conference at the Turin Motor Show — a veritable shrine of the auto industry at the time — was attended by the President of the Republic, Giovanni Gronchi. Coverage by leading newspapers around the world soon followed. The Pirelli BS3 was a tyre built around a carcass onto which three different tread rings could be mounted separately. It was perceived as a revolutionary invention, as we see in articles published in Rivista Pirelli no. 5 of 1959, and in the house organ Fatti e Notizie no. 10 of 1959. The project was launched by the engineer Carlo Barassi, then head of the Technological Office of Pirelli’s Tyre Technical Department at Milano Bicocca. During the particularly snowy winter of 1955–6, Barassi had revived an earlier invention by engineer Lugli that had never found practical application: a tyre in which carcass and tread were independent and interchangeable, vulcanised separately and held together solely by the pressure of inflation. In other words, “a tyre with a coat”.

From the outset, Ermanno Scopinich was involved in the communication campaign. It was he who created the evocative photographic and video shoot for the presentation, with the ice stadium in Cortina as its backdrop. The tyre’s technological advantages and its practical benefits for motorists are woven together in the ten-minute clip with feelings of comfort, driving pleasure and safety. The behind-the-scenes story of the product — its manufacturing processes and the expertise of skilled technicians — alternates with shots of skaters chasing an Alfa Romeo Giulietta, which remains steady on the ice thanks to the almost magical tread design of the BS3. Once again, it is Pirelli’s vision of winter that comes to the fore, balancing technological innovation with the promise of a new horizon: a season to be enjoyed to the full.

The third “winter tale” that we tell in this article centres on the hot-water bottle, Pirelli’s very first and long-standing product, created to offer comfort and protection from the cold. Listed in the catalogue as early as 1880, it inspired sketches and advertising campaigns in the 1950s, created by renowned artists such as Lora Lamm, Raymond Savignac and the Pagot brothers, many of whose works are now preserved in our Historical Archive. Yet Pirelli’s narrative has always been told in different ways and across multiple channels. By speaking different languages, it has reached different audiences, on different levels of meaning.

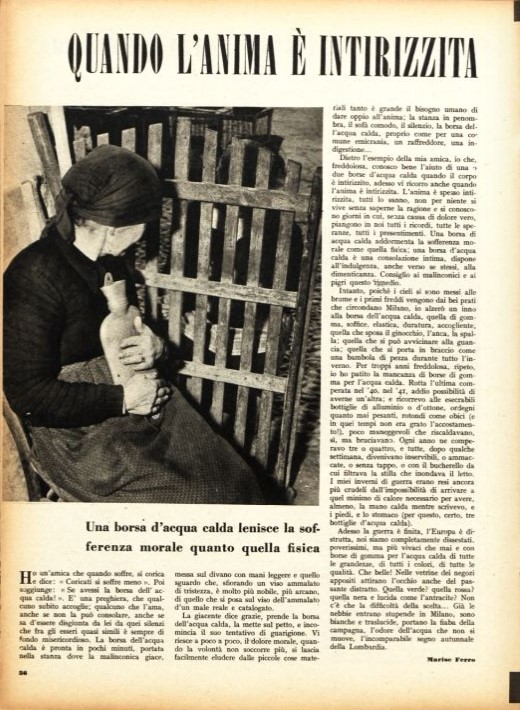

If we decide to turn our attention to the hot water bottle, not from the point of view of advertising but from that of journalism, we can take a look at the article by Marise Ferro published in Rivista Pirelli no. 5, 1949 “Quando l’anima è intirizzita” (“When the soul is numb”). This short autobiographical piece builds a world of meanings around the hot-water bottle, transforming it from just another useful object into an object of desire. It opens with a remark she remembers (“I have a friend who, when she is in pain, lies down and says: ‘You suffer less lying down!’ Then she adds: ‘If only I had a hot-water bottle!’”). And it continues with reflections (“The soul is often numb, as we all know; not for nothing do we live without knowing why… a hot-water bottle soothes our moral suffering as it does our physical pain.”) and memories (“My wartime winters were made even more cruel by the impossibility of achieving that minimum warmth needed to have, at the very least, a warm hand while I wrote…”). Through a chain of associations, the text arrives at a shared present that unites author and reader: “Now the war is over, Europe is in pieces, we are all completely broken and terribly poor, yet livelier than ever, and with rubber hot-water bottles of every size, every colour, every quality. How beautiful they are! In the shop windows they catch the eye even of the most distracted passer-by. The green one? The red one? The black one, as glossy as anthracite? The only difficulty is choosing…”. The image of shop windows with colourful Pirelli hot-water bottles tells the story of a season in search of light-heartedness and a measure of comfort after the years of war. This finds a contrasting yet harmonious counterpart in the autumnal landscape that closes this “ode to the hot-water bottle”, leaving us with a sense of absence, and the desire to have one of our own. “The mists are already drifting magnificently into Milan… bringing the fairy-tale of the countryside, the scent of still water, the incomparable autumnal signature of Lombardy.”

Pirelli and its winter products have inspired successful and memorable communication campaigns, thanks to an effective blend of technical content and value-driven messages. Together, they have shaped an innovative and engaging narrative: the allure of a season defined by comfort, safety, and pleasure

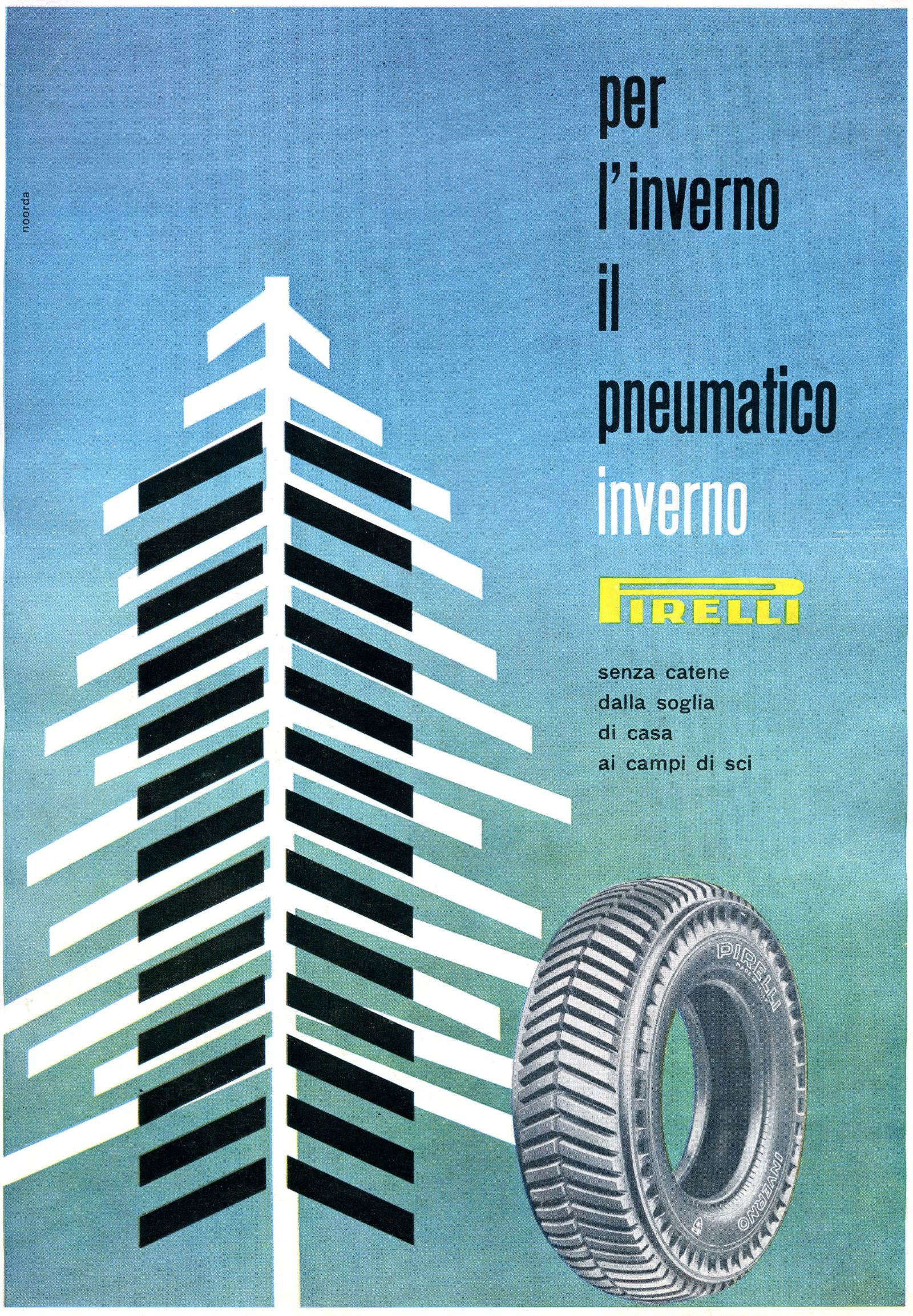

“Why do these artists forget the snow and the mountains? The skis? The icicles hanging from the roofs?” At first glance, Bob Noorda‘s stylised drawing for the advertising campaign for the Inverno tyre raised some doubts. We know this from a handwritten note on the back of the sketch entitled “per l’inverno il pneumatico inverno” (the idea being: “For winter: the Winter tyre”) preserved in our Historical Archive and catalogued as “tempera and collage on card with acetate sheet, with lettering”. The work dates from 1954 and is among the first commissions Pirelli entrusted to the young Dutch-born graphic designer. It was created to promote Pirelli’s first winter tyre, the Inverno, launched in 1951 and distinguished by its herringbone tread pattern. The author of the note, whose identity remains unknown, would clearly have wanted more realistic elements, like those that appeared in the advertisements designed by Ezio Bonini in the same years. Noorda had only recently arrived in Milan and was part of a community of graphic artists and designers who approached advertising as a design discipline. Their aim was clear, instant communication, achieved through the recognisability of the graphic element.

In this sketch too, Noorda eliminates everything superfluous. Yet his essential style is by no means pure abstraction. The impeccably clean lines of the decidedly wintry tree echo the herringbone tread, conveying with striking clarity the tyre’s defining technological feature.

Pirelli would go on to commission a remarkable number of works from Noorda and appoint him as art director in 1961. The relationship between the Milanese company and the Dutch designer quickly evolved increasingly reflecting Pirelli’s values, including in communication: an embrace of innovation.

In the autumn of 1959, the launch of the Pirelli BS3 was an international event. A press conference at the Turin Motor Show — a veritable shrine of the auto industry at the time — was attended by the President of the Republic, Giovanni Gronchi. Coverage by leading newspapers around the world soon followed. The Pirelli BS3 was a tyre built around a carcass onto which three different tread rings could be mounted separately. It was perceived as a revolutionary invention, as we see in articles published in Rivista Pirelli no. 5 of 1959, and in the house organ Fatti e Notizie no. 10 of 1959. The project was launched by the engineer Carlo Barassi, then head of the Technological Office of Pirelli’s Tyre Technical Department at Milano Bicocca. During the particularly snowy winter of 1955–6, Barassi had revived an earlier invention by engineer Lugli that had never found practical application: a tyre in which carcass and tread were independent and interchangeable, vulcanised separately and held together solely by the pressure of inflation. In other words, “a tyre with a coat”.

From the outset, Ermanno Scopinich was involved in the communication campaign. It was he who created the evocative photographic and video shoot for the presentation, with the ice stadium in Cortina as its backdrop. The tyre’s technological advantages and its practical benefits for motorists are woven together in the ten-minute clip with feelings of comfort, driving pleasure and safety. The behind-the-scenes story of the product — its manufacturing processes and the expertise of skilled technicians — alternates with shots of skaters chasing an Alfa Romeo Giulietta, which remains steady on the ice thanks to the almost magical tread design of the BS3. Once again, it is Pirelli’s vision of winter that comes to the fore, balancing technological innovation with the promise of a new horizon: a season to be enjoyed to the full.

The third “winter tale” that we tell in this article centres on the hot-water bottle, Pirelli’s very first and long-standing product, created to offer comfort and protection from the cold. Listed in the catalogue as early as 1880, it inspired sketches and advertising campaigns in the 1950s, created by renowned artists such as Lora Lamm, Raymond Savignac and the Pagot brothers, many of whose works are now preserved in our Historical Archive. Yet Pirelli’s narrative has always been told in different ways and across multiple channels. By speaking different languages, it has reached different audiences, on different levels of meaning.

If we decide to turn our attention to the hot water bottle, not from the point of view of advertising but from that of journalism, we can take a look at the article by Marise Ferro published in Rivista Pirelli no. 5, 1949 “Quando l’anima è intirizzita” (“When the soul is numb”). This short autobiographical piece builds a world of meanings around the hot-water bottle, transforming it from just another useful object into an object of desire. It opens with a remark she remembers (“I have a friend who, when she is in pain, lies down and says: ‘You suffer less lying down!’ Then she adds: ‘If only I had a hot-water bottle!’”). And it continues with reflections (“The soul is often numb, as we all know; not for nothing do we live without knowing why… a hot-water bottle soothes our moral suffering as it does our physical pain.”) and memories (“My wartime winters were made even more cruel by the impossibility of achieving that minimum warmth needed to have, at the very least, a warm hand while I wrote…”). Through a chain of associations, the text arrives at a shared present that unites author and reader: “Now the war is over, Europe is in pieces, we are all completely broken and terribly poor, yet livelier than ever, and with rubber hot-water bottles of every size, every colour, every quality. How beautiful they are! In the shop windows they catch the eye even of the most distracted passer-by. The green one? The red one? The black one, as glossy as anthracite? The only difficulty is choosing…”. The image of shop windows with colourful Pirelli hot-water bottles tells the story of a season in search of light-heartedness and a measure of comfort after the years of war. This finds a contrasting yet harmonious counterpart in the autumnal landscape that closes this “ode to the hot-water bottle”, leaving us with a sense of absence, and the desire to have one of our own. “The mists are already drifting magnificently into Milan… bringing the fairy-tale of the countryside, the scent of still water, the incomparable autumnal signature of Lombardy.”