The importance of knowledge in the age AI: Journalism put to the test against fake news that distorts democracy and society

‘If the photo didn’t turn out well, it means you weren’t close enough.’ said Robert Capa, one of the greatest photojournalists of the 20th century. He never shied away from risk in his work. During the Spanish Civil War, and on D-Day in Normandy in June 1944. He was also on the ground in the Arab-Israeli War of 1948. And in Indochina in 1954. It was there, in the province of Thai Binh, that he got too close to a mine. He was 41 years old. His colleague and partner, Gerda Taro, was 26.

She was run over by a tank on the outskirts of Madrid in July 1937.

They had lived their lives to tell the story. To bear witness. To make people understand. Through an image, a piece of writing or a TV shot. Journalism is a job. But it is also a lifestyle choice. One that sometimes comes at the terrible price of death.

As Capa said, it’s about being ‘close enough’. Close to the objective truth that reporting, analysis and investigation allow us to see and portray.

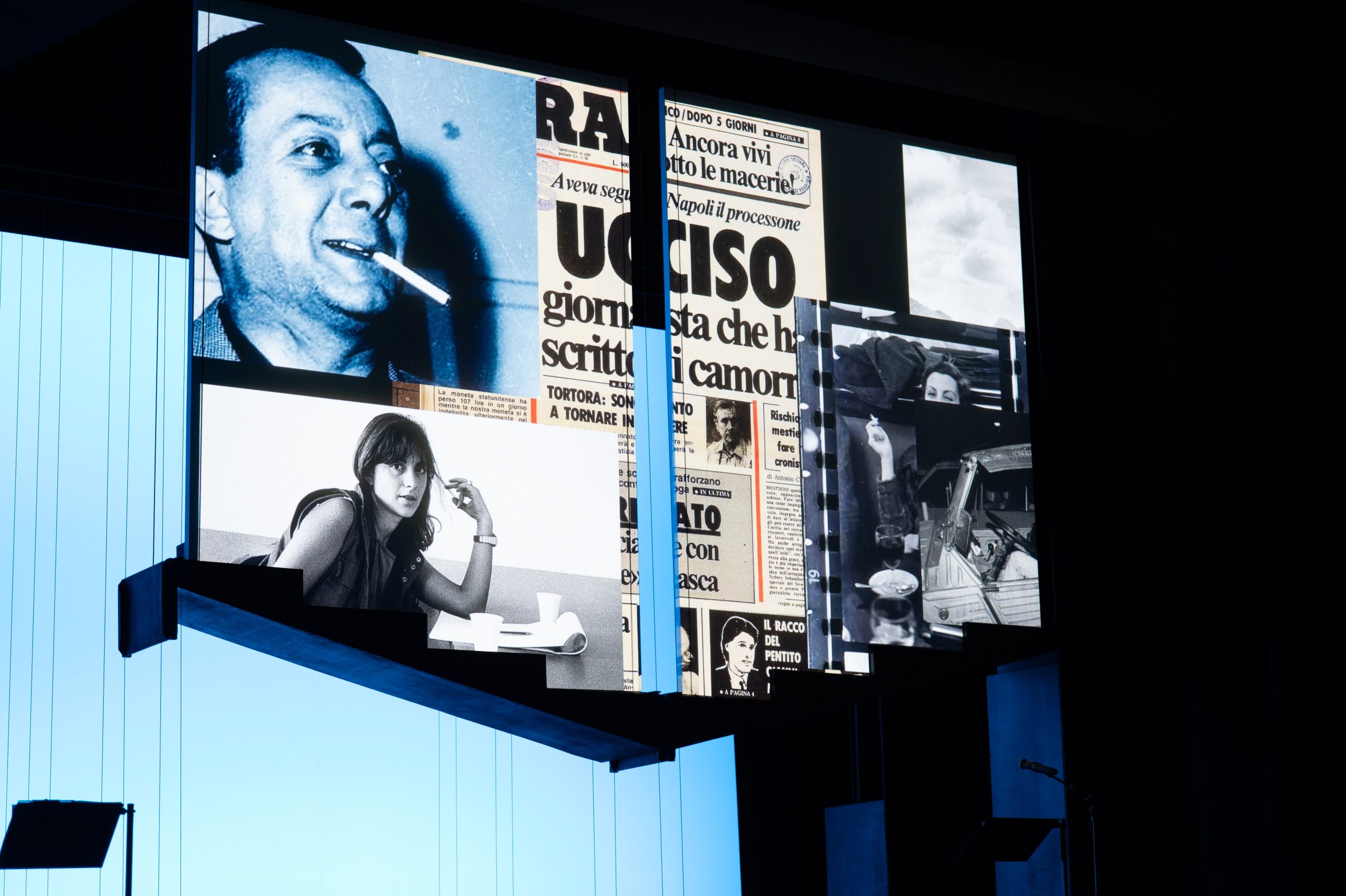

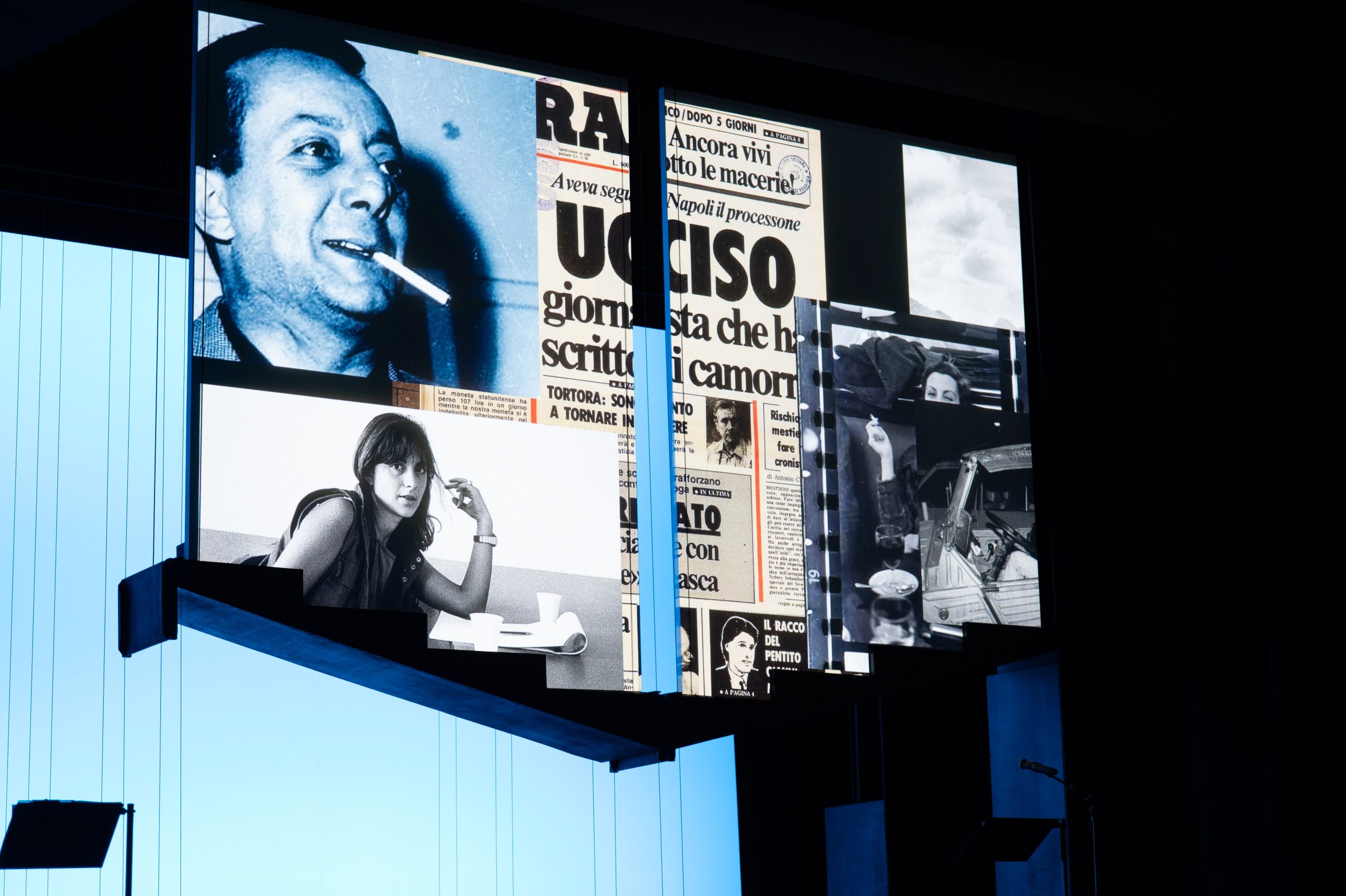

These words were echoed at the end of September during the opening ceremony for the winners of ‘Il Premiolino’, one of Italy’s oldest journalism awards. Founded in 1960 by Enzo Biagi, Indro Montanelli, Orio Vergani and other prominent figures in the daily newspaper industry, the ceremony took place at the Piccolo Teatro in Milan. Meanwhile, an actress’s voice, off-screen, recalled the names of Mauro De Mauro, Mario Francese, Mauro Rostagno, Pippo Fava and Giancarlo Siani — journalists who wrote about the mafia’s involvement in crime, business and power. Also mentioned were Carlo Casalegno and Walter Tobagi, who were committed to uncovering the horrors of terrorism in the 1970s, as well as Maria Grazia Cutuli in Afghanistan, Ilaria Alpi and Miran Hrovatin in Mogadishu, and Anna Politkovskaya in Russia. And many others from Europe and around the world.

The evening was dedicated to them, and saw the honouring of ‘good journalism, a diligent and rigorous interpreter of truth, civilisation, humanity, and the sense of democracy’. Remembering, also, the reporters who died in Gaza, just a few days ago. And Victoria Roshchyna, another exemplary and courageous woman, in Ukraine.

All these names, ‘read aloud with solidarity and respect, dramatically express the meaning and value of the journalism profession.’ It is a profession with strong moral and civic connotations, ‘fitting for those women and men who love freedom and responsibility. However, it is ill-suited to ‘cynics’, as that extraordinary master, Ryszard Kapuściński, taught us’.

This ceremony commemorates the dead in a way that goes beyond mere remembrance. One that values the words spoken and written in newspapers, online, on the radio and on television year after year. It acknowledges the past, present and future, emphasising that good information is fundamental to our civil and democratic coexistence and our commitment to future generations.

The Premiolino jury (chaired by Chiara Beria di Argentine and supported by Pirelli), this year recognised Paolo Giordano (Corriere della Sera), Anna Zafesova (La Stampa), Luigi Manconi (la Repubblica), Siegmund Ginzberg (Il Foglio), Thomas Mackinson (Il Fatto Quotidiano), Sabrina Giannini (Rai3). The Pirelli Prize for Schools went to Gianna Fregonara and Orsola Riva (Corriere della Sera). The awards recognised the wide range of issues covered and the constant provision of evidence of cultural and social value during such a difficult and controversial period.

The fact is that these are not easy times for journalists. They are undermined by the general loss of credibility that has affected the elite, intellectuals, scientists and competent individuals for far too long (the overwhelming expansion of social media on the internet has helped to spread the misconception that ‘my ignorance is worth as much as your knowledge’). The media system is being affected by radical technological and cultural transformations, for which there are no editorial or political responses capable of meeting the challenge yet. Maligned by political and economic powers that detest criticism and prefer to cultivate fake news and post-truths. They are considered marginal by a widespread public opinion that does not view information as a fundamental community asset and relies on factoids instead of engaging with facts, data and truth, including when they are uncomfortable or inconvenient for a social group, interest group or corporation.

As with all crises, those in the worlds of culture, science and information must also take responsibility. One thing is clear, however: without quality information, the world would be an even worse, more unjust and unbalanced place, and democracy, the market economy, welfare and social solidarity systems, and all the knowledge mechanisms that affect quality of life, work and relationships would suffer.

In recent days, during a speech in Tallinn, Estonia, the President of the Republic, Sergio Mattarella, who has always been keenly aware of the issues relating to democracy, as well as the relationships between powers and cultures that form the basis of participation and citizenship, recalled that ‘the challenges posed by artificial intelligence are complex, but democracies cannot afford to be left behind… It is up to us to create an AI that protects our citizens and our values without undermining them’.

This is a key point: ‘Technology and security are closely interconnected issues that are increasingly central to our democratic communities’ insists Mattarella. ‘We are witnessing an increasing use of AI for disinformation purposes, as well as to influence public opinion, through the unscrupulous use of user profiling on social media and the equally unscrupulous dissemination of fake news.’

Therefore, ‘binding global standards’ are needed to govern the processes set in motion by AI, and there must be widespread awareness of both the opportunities and risks related to new technologies.

The antidote? Invest in knowledge, the humanities and the sciences, and foster a deeper sense of responsibility within public opinion. This may be difficult to achieve, but it is essential to try with conviction.

These are issues that were also central to Pope Leo’s reflections. ‘Free information is a pillar that supports the construction of our societies and, for this reason, we are called upon to defend and guarantee it,’ he said in recent days in a message to Minds, the association of leading press agencies. To combat ‘junk information’, we need ‘competence, courage and a sense of ethics’: journalists can ‘act as a bulwark against those who, through the ancient art of lying, seek to create divisions in order to rule by dividing; a bastion of civilisation against the quicksand of approximation and post-truth’.

Journalism, Pope Leo insists, ‘is not a crime’. And we must thank ‘the reporters who put themselves at risk so that people can understand how things really are’.

The Pope asked journalists to ‘free communication from the cognitive pollution that corrupts it; from unfair competition; and from the degradation of clickbait.’ In short, ‘we are not destined to live in a world where truth is indistinguishable from fiction.’ In his view, ‘algorithms generate content and data at a speed and in a dimension that has never been seen before, but who governs them? Artificial intelligence is changing the way we inform ourselves and communicate, but who is driving it and for what purposes?’ W must ensure that technology does not replace man, and that the information and algorithms that govern it today are not in the hands of a few.’

Fortunately, these issues are receiving increasing attention from journalists and publishers, as was evident from the recent debate on the evolution of the media at the Il Sole 24 Ore conference. Two of the keynote speeches illustrate this well. The first was delivered by Agnese Pini, editor-in-chief of QN/La Nazione, Il Resto del Carlino and Il Giorno, who said: ‘Information is the third channel between power and citizens. If this filter is removed, power speaks directly to citizens in a vertical manner, and a fundamental guarantee for democracy is lost.’ There is, in fact, a perverse relationship between the spread of social media and the collapse in reading rates from 2011-2012 to the present day. And we must face the challenge of improving knowledge processes and good information.

Giuseppe De Bellis, the editorial director of SkyTG24, adds, ‘In the vast landscape of information, which is often inaccurate, overly sensationalised, and verging on misinformation, all publications with a historical legacy that operate in the digital ecosystem through websites and social media must encourage consumers and readers to visit their platforms by focusing on authority and credibility.’

In short, the challenge of acquiring knowledge and good information is difficult, but not insurmountable.

There is an interesting opportunity for reflection in the coming year, a year of symbolic anniversaries for the world of newspapers: the 159th anniversary of the founding of the Corriere della Sera, the 70th anniversary of Il Giorno, and the 50th anniversary of la Repubblica. Another notable and unfortunate anniversary is the closure of Il Mondo, the weekly magazine edited by Mario Pannunzio, on 8 March 1966. It was a training ground for solid, high-quality journalism, but above all it fostered an intense civic, secular, liberal and socially sensitive outlook.

Occasions such as this are sometimes at risk of celebratory rhetoric and nostalgic reminiscence. This time, it would be worthwhile for the worlds of information, politics, economics and culture to take advantage of the opportunity to think seriously, deeply and impartially about the essential relationship between journalism and democracy; the need to improve levels of information and knowledge; and the shift in publishing from an economic enterprise to a strong, deep-rooted civic endeavour.

As Carlo Levi taught us, words are like stones: indispensable for strengthening the buildings of our freedoms.

(photo Ippi Studio)

‘If the photo didn’t turn out well, it means you weren’t close enough.’ said Robert Capa, one of the greatest photojournalists of the 20th century. He never shied away from risk in his work. During the Spanish Civil War, and on D-Day in Normandy in June 1944. He was also on the ground in the Arab-Israeli War of 1948. And in Indochina in 1954. It was there, in the province of Thai Binh, that he got too close to a mine. He was 41 years old. His colleague and partner, Gerda Taro, was 26.

She was run over by a tank on the outskirts of Madrid in July 1937.

They had lived their lives to tell the story. To bear witness. To make people understand. Through an image, a piece of writing or a TV shot. Journalism is a job. But it is also a lifestyle choice. One that sometimes comes at the terrible price of death.

As Capa said, it’s about being ‘close enough’. Close to the objective truth that reporting, analysis and investigation allow us to see and portray.

These words were echoed at the end of September during the opening ceremony for the winners of ‘Il Premiolino’, one of Italy’s oldest journalism awards. Founded in 1960 by Enzo Biagi, Indro Montanelli, Orio Vergani and other prominent figures in the daily newspaper industry, the ceremony took place at the Piccolo Teatro in Milan. Meanwhile, an actress’s voice, off-screen, recalled the names of Mauro De Mauro, Mario Francese, Mauro Rostagno, Pippo Fava and Giancarlo Siani — journalists who wrote about the mafia’s involvement in crime, business and power. Also mentioned were Carlo Casalegno and Walter Tobagi, who were committed to uncovering the horrors of terrorism in the 1970s, as well as Maria Grazia Cutuli in Afghanistan, Ilaria Alpi and Miran Hrovatin in Mogadishu, and Anna Politkovskaya in Russia. And many others from Europe and around the world.

The evening was dedicated to them, and saw the honouring of ‘good journalism, a diligent and rigorous interpreter of truth, civilisation, humanity, and the sense of democracy’. Remembering, also, the reporters who died in Gaza, just a few days ago. And Victoria Roshchyna, another exemplary and courageous woman, in Ukraine.

All these names, ‘read aloud with solidarity and respect, dramatically express the meaning and value of the journalism profession.’ It is a profession with strong moral and civic connotations, ‘fitting for those women and men who love freedom and responsibility. However, it is ill-suited to ‘cynics’, as that extraordinary master, Ryszard Kapuściński, taught us’.

This ceremony commemorates the dead in a way that goes beyond mere remembrance. One that values the words spoken and written in newspapers, online, on the radio and on television year after year. It acknowledges the past, present and future, emphasising that good information is fundamental to our civil and democratic coexistence and our commitment to future generations.

The Premiolino jury (chaired by Chiara Beria di Argentine and supported by Pirelli), this year recognised Paolo Giordano (Corriere della Sera), Anna Zafesova (La Stampa), Luigi Manconi (la Repubblica), Siegmund Ginzberg (Il Foglio), Thomas Mackinson (Il Fatto Quotidiano), Sabrina Giannini (Rai3). The Pirelli Prize for Schools went to Gianna Fregonara and Orsola Riva (Corriere della Sera). The awards recognised the wide range of issues covered and the constant provision of evidence of cultural and social value during such a difficult and controversial period.

The fact is that these are not easy times for journalists. They are undermined by the general loss of credibility that has affected the elite, intellectuals, scientists and competent individuals for far too long (the overwhelming expansion of social media on the internet has helped to spread the misconception that ‘my ignorance is worth as much as your knowledge’). The media system is being affected by radical technological and cultural transformations, for which there are no editorial or political responses capable of meeting the challenge yet. Maligned by political and economic powers that detest criticism and prefer to cultivate fake news and post-truths. They are considered marginal by a widespread public opinion that does not view information as a fundamental community asset and relies on factoids instead of engaging with facts, data and truth, including when they are uncomfortable or inconvenient for a social group, interest group or corporation.

As with all crises, those in the worlds of culture, science and information must also take responsibility. One thing is clear, however: without quality information, the world would be an even worse, more unjust and unbalanced place, and democracy, the market economy, welfare and social solidarity systems, and all the knowledge mechanisms that affect quality of life, work and relationships would suffer.

In recent days, during a speech in Tallinn, Estonia, the President of the Republic, Sergio Mattarella, who has always been keenly aware of the issues relating to democracy, as well as the relationships between powers and cultures that form the basis of participation and citizenship, recalled that ‘the challenges posed by artificial intelligence are complex, but democracies cannot afford to be left behind… It is up to us to create an AI that protects our citizens and our values without undermining them’.

This is a key point: ‘Technology and security are closely interconnected issues that are increasingly central to our democratic communities’ insists Mattarella. ‘We are witnessing an increasing use of AI for disinformation purposes, as well as to influence public opinion, through the unscrupulous use of user profiling on social media and the equally unscrupulous dissemination of fake news.’

Therefore, ‘binding global standards’ are needed to govern the processes set in motion by AI, and there must be widespread awareness of both the opportunities and risks related to new technologies.

The antidote? Invest in knowledge, the humanities and the sciences, and foster a deeper sense of responsibility within public opinion. This may be difficult to achieve, but it is essential to try with conviction.

These are issues that were also central to Pope Leo’s reflections. ‘Free information is a pillar that supports the construction of our societies and, for this reason, we are called upon to defend and guarantee it,’ he said in recent days in a message to Minds, the association of leading press agencies. To combat ‘junk information’, we need ‘competence, courage and a sense of ethics’: journalists can ‘act as a bulwark against those who, through the ancient art of lying, seek to create divisions in order to rule by dividing; a bastion of civilisation against the quicksand of approximation and post-truth’.

Journalism, Pope Leo insists, ‘is not a crime’. And we must thank ‘the reporters who put themselves at risk so that people can understand how things really are’.

The Pope asked journalists to ‘free communication from the cognitive pollution that corrupts it; from unfair competition; and from the degradation of clickbait.’ In short, ‘we are not destined to live in a world where truth is indistinguishable from fiction.’ In his view, ‘algorithms generate content and data at a speed and in a dimension that has never been seen before, but who governs them? Artificial intelligence is changing the way we inform ourselves and communicate, but who is driving it and for what purposes?’ W must ensure that technology does not replace man, and that the information and algorithms that govern it today are not in the hands of a few.’

Fortunately, these issues are receiving increasing attention from journalists and publishers, as was evident from the recent debate on the evolution of the media at the Il Sole 24 Ore conference. Two of the keynote speeches illustrate this well. The first was delivered by Agnese Pini, editor-in-chief of QN/La Nazione, Il Resto del Carlino and Il Giorno, who said: ‘Information is the third channel between power and citizens. If this filter is removed, power speaks directly to citizens in a vertical manner, and a fundamental guarantee for democracy is lost.’ There is, in fact, a perverse relationship between the spread of social media and the collapse in reading rates from 2011-2012 to the present day. And we must face the challenge of improving knowledge processes and good information.

Giuseppe De Bellis, the editorial director of SkyTG24, adds, ‘In the vast landscape of information, which is often inaccurate, overly sensationalised, and verging on misinformation, all publications with a historical legacy that operate in the digital ecosystem through websites and social media must encourage consumers and readers to visit their platforms by focusing on authority and credibility.’

In short, the challenge of acquiring knowledge and good information is difficult, but not insurmountable.

There is an interesting opportunity for reflection in the coming year, a year of symbolic anniversaries for the world of newspapers: the 159th anniversary of the founding of the Corriere della Sera, the 70th anniversary of Il Giorno, and the 50th anniversary of la Repubblica. Another notable and unfortunate anniversary is the closure of Il Mondo, the weekly magazine edited by Mario Pannunzio, on 8 March 1966. It was a training ground for solid, high-quality journalism, but above all it fostered an intense civic, secular, liberal and socially sensitive outlook.

Occasions such as this are sometimes at risk of celebratory rhetoric and nostalgic reminiscence. This time, it would be worthwhile for the worlds of information, politics, economics and culture to take advantage of the opportunity to think seriously, deeply and impartially about the essential relationship between journalism and democracy; the need to improve levels of information and knowledge; and the shift in publishing from an economic enterprise to a strong, deep-rooted civic endeavour.

As Carlo Levi taught us, words are like stones: indispensable for strengthening the buildings of our freedoms.

(photo Ippi Studio)