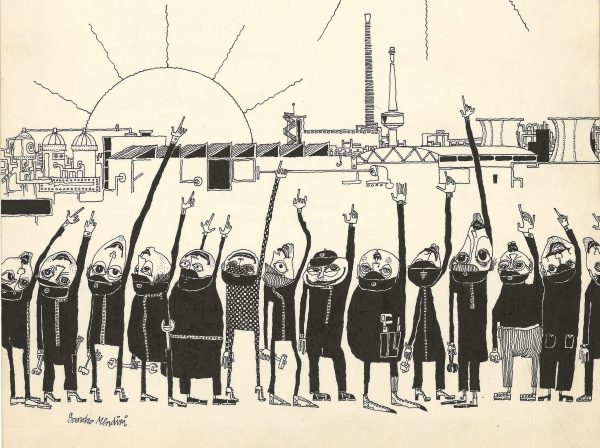

Social Innovation in Enterprise

Business leaders and their management today need to keep a keen eye on the environment and how it impacts on the organisation of the business and, at the end of the day, on achieving their objectives, as well as on the ongoing interaction between enterprise and society, between the organisation and its members and the rest of the world—interaction with can, in many cases, actually be positive. It is a matter of business development and the evolution of society, but also of greater awareness of the role that enterprise plays in the structure of modern society. In short, it’s the culture of enterprise becoming broader and more complete.

It is within this context that we see the rise of corporate social responsibility (CSR), i.e. an enterprise’s constant focus on the outside world, and how this ties into the concept of social innovation (SI). Pondering the complex, constantly changing interplay between CSR and SI can, if done properly, be of great utility to any business leader hoping stand out from the pack, which makes “Modelli ed esperienze di innovazione sociale in Italia. Secondo rapporto sull’innovazione sociale” (Models and experiences in social innovation in Italy. Second report on social innovation), edited by Matteo G. Caroli (director of the Centre for International Research on Social Innovation, or CERIIS, at LUISS Guido Carli University) and with the contribution of multiple authors who have written about social innovation and its great many interactions with business and enterprise.

After providing an overview of the related theory, the book takes a close look at the relationship between CSR and SI. On particular passage states that “economic value is achieved by defining a business model that is able to channel the economic, environmental and social sustainability of innovative practices”. Beyond the theory, the book also includes interviews with 26 enterprises to come up with important tips on how to achieve social innovation in enterprise.

It is also explained that “an enterprise is positioned at a stage of the value chain in which it is able to build economic and social value in its product or service”. The other parties involved are either on the demand side, as customers and consumers, or on the supply side, as “producers, business owners, or employees of the hybrid organisation”. But what is the enterprise’s relationship with SI? Is it all only about profits? The authors featured in this work would say no. Any enterprise can be a doer, a promoter, or even a beneficiary, depending on the social issue at hand and the role that is actually required. The benefit that the enterprise derives from any action of social innovation is collective, and the benefits must also go to the enterprise itself.

This work by CERIIS is not always easy to read, but it is a thorough exploration of a vast territory that brings together both business and society.

Modelli ed esperienze di innovazione sociale in Italia. Secondo rapporto sull’innovazione sociale

Matteo G. Caroli (editor)

Franco Angeli, 2016

Business leaders and their management today need to keep a keen eye on the environment and how it impacts on the organisation of the business and, at the end of the day, on achieving their objectives, as well as on the ongoing interaction between enterprise and society, between the organisation and its members and the rest of the world—interaction with can, in many cases, actually be positive. It is a matter of business development and the evolution of society, but also of greater awareness of the role that enterprise plays in the structure of modern society. In short, it’s the culture of enterprise becoming broader and more complete.

It is within this context that we see the rise of corporate social responsibility (CSR), i.e. an enterprise’s constant focus on the outside world, and how this ties into the concept of social innovation (SI). Pondering the complex, constantly changing interplay between CSR and SI can, if done properly, be of great utility to any business leader hoping stand out from the pack, which makes “Modelli ed esperienze di innovazione sociale in Italia. Secondo rapporto sull’innovazione sociale” (Models and experiences in social innovation in Italy. Second report on social innovation), edited by Matteo G. Caroli (director of the Centre for International Research on Social Innovation, or CERIIS, at LUISS Guido Carli University) and with the contribution of multiple authors who have written about social innovation and its great many interactions with business and enterprise.

After providing an overview of the related theory, the book takes a close look at the relationship between CSR and SI. On particular passage states that “economic value is achieved by defining a business model that is able to channel the economic, environmental and social sustainability of innovative practices”. Beyond the theory, the book also includes interviews with 26 enterprises to come up with important tips on how to achieve social innovation in enterprise.

It is also explained that “an enterprise is positioned at a stage of the value chain in which it is able to build economic and social value in its product or service”. The other parties involved are either on the demand side, as customers and consumers, or on the supply side, as “producers, business owners, or employees of the hybrid organisation”. But what is the enterprise’s relationship with SI? Is it all only about profits? The authors featured in this work would say no. Any enterprise can be a doer, a promoter, or even a beneficiary, depending on the social issue at hand and the role that is actually required. The benefit that the enterprise derives from any action of social innovation is collective, and the benefits must also go to the enterprise itself.

This work by CERIIS is not always easy to read, but it is a thorough exploration of a vast territory that brings together both business and society.

Modelli ed esperienze di innovazione sociale in Italia. Secondo rapporto sull’innovazione sociale

Matteo G. Caroli (editor)

Franco Angeli, 2016