In an ageing Italy, the political challenge lies in investing in the future and creating jobs for young people

Italy is an ageing country. The average age is currently 48.7 years and is rising year on year. It is already the highest average age among EU countries (Eurostat data). At the same time, it is the country with the lowest birth rate, at 1.18%. According to Istat, just 370,000 children were born in 2024, which was 2.6% fewer than the previous year. In the first six months of 2025, there were 13,000 fewer births than in the same period in 2024.

And the crisis doesn’t end there. Young people are looking elsewhere for better working and living conditions. ‘In the last ten years, over 337,000 young Italians, including 120,000 graduates, have left the country,’ says Riccardo Di Stefano, Confindustria’s vice-president for Education and Open Innovation. Moreover, those who remain are neither valued nor afforded prospects for the future: there are 1.3 million NEETs (Not in Education, Employment or Training) aged 15–29, representing 15.2% of their age group.

In short, we are experiencing an alarming ‘demographic winter’, characterised by an ageing population (life expectancy has risen to an average of 83.4 years) and falling birth rates. To make matters worse, too large a proportion of the younger generation is being kept out of work and out of the ‘knowledge economy’.

The issue, which has been neglected for years, has finally come to the forefront of public discourse, with growing interest in demographic studies and journalistic investigations. However, despite the availability of data, there are still no signs of political decisions being taken to address the related economic, social and cultural issues.

According to Istat, children will account for only 11.2% of the population by 2050. This will lead to empty schools and unemployed teachers. Over the next few years, there will also be a shortage of workers and entrepreneurs unless solid immigration policies are put in place. Resources to pay for welfare, including pensions for the growing elderly population, will also decrease.

Demographics are a phenomenon of long-term trends. Even if the low birth rate were miraculously halted and reversed, it would take at least twenty years for today’s newborns to have an impact on the labour market. So, to address these issues, we need to make timely decisions and implement intelligent policy measures to deal with the interim situations.

But where? The trend towards low birth rates has psychological, economic and cultural roots. These include the crisis of the traditional family and a change in values, with an increased focus on individual expectations rather than parental responsibilities and the sense of community. Other factors include the structures and trends of the labour market, which still marginalise many women, and the serious shortage of housing and services in large urban centres, including nurseries and full-time schools. And, above all, the loss of confidence in the future.

The key issue is a crisis of confidence. The ‘generational pact’ (the idea that our children will enjoy a better quality of life than us, so it’s worth investing in their education and creating opportunities for them) began to break down in Italy in the early 1980s due to the explosion of public debt. In short, the cost of the current generation’s well-being was passed on to the next generation. In all other Western countries, welfare maintenance, starting with pensions, was funded by debt passed on to children and grandchildren.

Tensions and generational divides have been exacerbated by international geopolitical tensions, environmental disasters, trade wars, growing social unrest, and the difficulty of maintaining the same quality of life as their parents. Having children is no longer a priority.

Breaking this cycle is extremely difficult. Yet something urgent and forward-looking must be done to avoid resigning ourselves to a fate of decline and degradation, a loss of momentum for innovation, not only economic, but also social and cultural. This would represent a radical crisis of all that Europe and the West have built up over the course of the 20th century, especially in its second half: the synthesis of liberal democracy, the market economy and welfare, that is, a balance between freedom, enterprise and the values of change and solidarity; progress and social cohesion.

So, we need to rethink politics, work and participation, and finally learn to link our long-term ambitions for change with the pragmatic reformism of good governance —

a difficult balance to strike. However, it is possible if we heed the words of one of the finest intellectuals of the 20th century, Ernst Cassirer: ‘The great mission of the Utopia is to make room for the possible as opposed to a passive acquiescence in the present actual state of affairs. It is symbolic thought which overcomes the natural inertia of man and endows him with a new ability, the ability constantly to reshape his human universe.’

Therefore, bearing in mind Cassirer’s thinking alongside that of Lewis Mumford, we should note the distinction (which readers of this blog will already be familiar with) between a ‘utopia of escape’, which is the desire to build castles in the air, and a ‘utopia of reconstruction’, which is the commitment to imagining and implementing ambitious change. However, we must also think practically about good politics here and now.

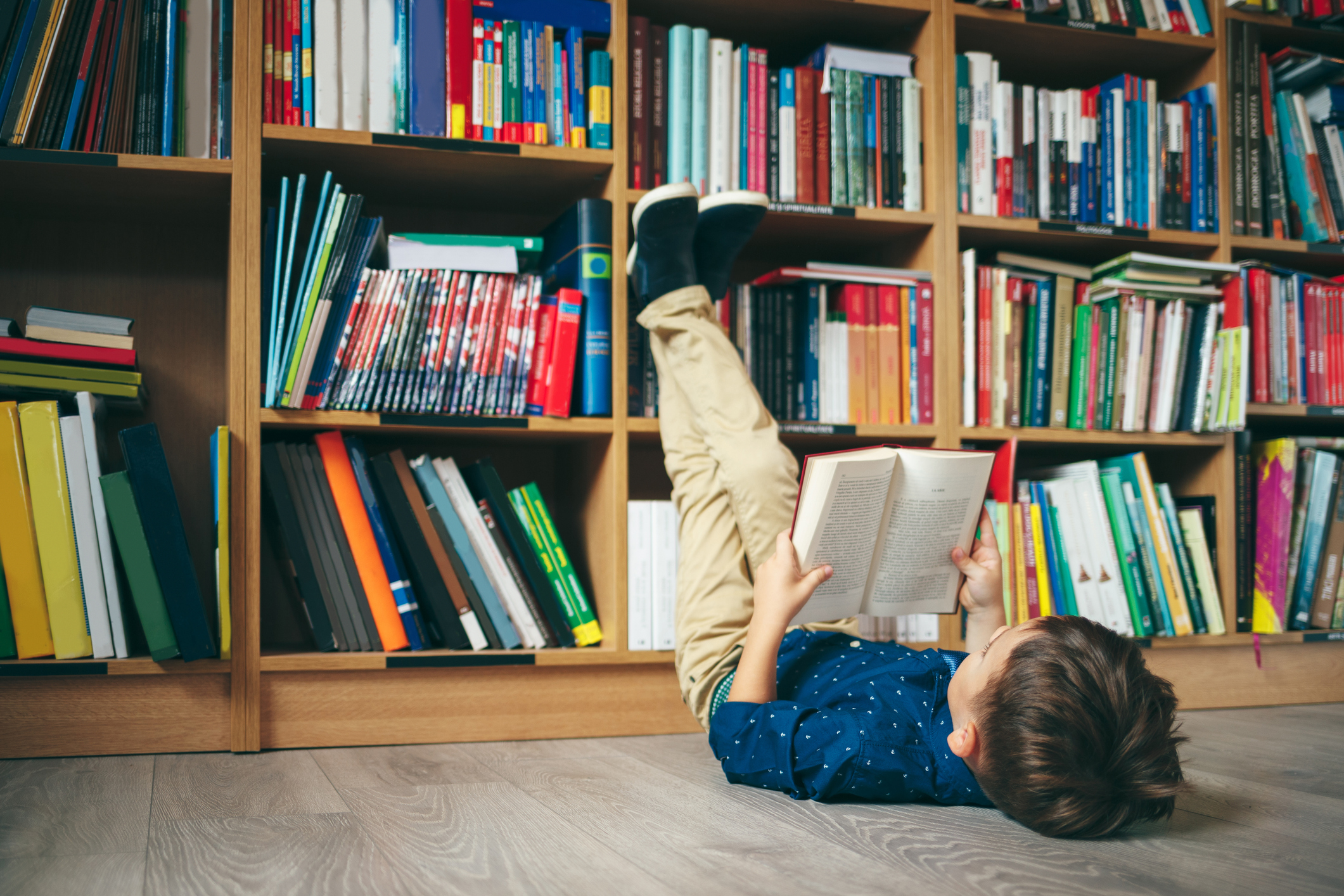

How? Rebuilding trust is a general goal (we discussed this in blogs on 6 May and 7 October). To give the new generations a sense of purpose and the prospect of change. But in the meantime, make practical choices. We should make better use of the resources we have, namely women and young people, by guaranteeing them better access to the job market with career policies and incomes suited to their training, enabling them to transform their ambitions into enterprise and industriousness. We must change the cycle of Italy being abandoned by its most enterprising and active young people by offering growth opportunities and, at the same time, attracting new human resources from abroad, especially from the Mediterranean basin. We need to insist on education and bridge the knowledge and understanding gap (a third of Italians are ‘functionally illiterate’, meaning they cannot understand a written text of medium complexity or do basic maths). Finally, we have to commit adequate financial and intellectual resources to reintegrating a large portion of those NEETs we mentioned into civil coexistence and therefore responsible participation.

This is not a catalogue of good intentions, but rather an indication of the parts that make up a balanced plan for the development of Italy within Europe. It is a list of points that must be translated into government choices, investments (EU funds must be used wisely) and commitments involving not only political decision-makers, but also economic and cultural actors.

It is a difficult challenge, of course, but a key step for economic growth and, above all, for social balance.

A ‘citizenship collaboration’, according to Confindustria, at the end of a conference in Ortigia on Open Innovation and training, precisely to ‘highlight talent, knowledge, technology and productivity’ (Il Sole24Ore, 24 and 25 October). And The Young Entrepreneurs of Confindustria, chaired by Maria Anghileri, emphasise in their conferences the importance of opening up the company to new generations as a space in which to realise projects, ideas, ambitions and dreams. ‘The growing enterprise’ is their stated goal. Enterprise as an economic actor and a social catalyst.

From this point of view, the political choice is clear: the strategy we need is one of knowledge, innovation and training, particularly from an industrial policy perspective.

If our resources are limited, it is essential to invest in training our young people. This will enable them to reach their full potential. In the meantime, we must work to reverse the cycle of fearful closure in social microcosms and falling birth rates. We must invest in rebuilding trust and developing a positive vision for the future.

(photo Getty Images)

Italy is an ageing country. The average age is currently 48.7 years and is rising year on year. It is already the highest average age among EU countries (Eurostat data). At the same time, it is the country with the lowest birth rate, at 1.18%. According to Istat, just 370,000 children were born in 2024, which was 2.6% fewer than the previous year. In the first six months of 2025, there were 13,000 fewer births than in the same period in 2024.

And the crisis doesn’t end there. Young people are looking elsewhere for better working and living conditions. ‘In the last ten years, over 337,000 young Italians, including 120,000 graduates, have left the country,’ says Riccardo Di Stefano, Confindustria’s vice-president for Education and Open Innovation. Moreover, those who remain are neither valued nor afforded prospects for the future: there are 1.3 million NEETs (Not in Education, Employment or Training) aged 15–29, representing 15.2% of their age group.

In short, we are experiencing an alarming ‘demographic winter’, characterised by an ageing population (life expectancy has risen to an average of 83.4 years) and falling birth rates. To make matters worse, too large a proportion of the younger generation is being kept out of work and out of the ‘knowledge economy’.

The issue, which has been neglected for years, has finally come to the forefront of public discourse, with growing interest in demographic studies and journalistic investigations. However, despite the availability of data, there are still no signs of political decisions being taken to address the related economic, social and cultural issues.

According to Istat, children will account for only 11.2% of the population by 2050. This will lead to empty schools and unemployed teachers. Over the next few years, there will also be a shortage of workers and entrepreneurs unless solid immigration policies are put in place. Resources to pay for welfare, including pensions for the growing elderly population, will also decrease.

Demographics are a phenomenon of long-term trends. Even if the low birth rate were miraculously halted and reversed, it would take at least twenty years for today’s newborns to have an impact on the labour market. So, to address these issues, we need to make timely decisions and implement intelligent policy measures to deal with the interim situations.

But where? The trend towards low birth rates has psychological, economic and cultural roots. These include the crisis of the traditional family and a change in values, with an increased focus on individual expectations rather than parental responsibilities and the sense of community. Other factors include the structures and trends of the labour market, which still marginalise many women, and the serious shortage of housing and services in large urban centres, including nurseries and full-time schools. And, above all, the loss of confidence in the future.

The key issue is a crisis of confidence. The ‘generational pact’ (the idea that our children will enjoy a better quality of life than us, so it’s worth investing in their education and creating opportunities for them) began to break down in Italy in the early 1980s due to the explosion of public debt. In short, the cost of the current generation’s well-being was passed on to the next generation. In all other Western countries, welfare maintenance, starting with pensions, was funded by debt passed on to children and grandchildren.

Tensions and generational divides have been exacerbated by international geopolitical tensions, environmental disasters, trade wars, growing social unrest, and the difficulty of maintaining the same quality of life as their parents. Having children is no longer a priority.

Breaking this cycle is extremely difficult. Yet something urgent and forward-looking must be done to avoid resigning ourselves to a fate of decline and degradation, a loss of momentum for innovation, not only economic, but also social and cultural. This would represent a radical crisis of all that Europe and the West have built up over the course of the 20th century, especially in its second half: the synthesis of liberal democracy, the market economy and welfare, that is, a balance between freedom, enterprise and the values of change and solidarity; progress and social cohesion.

So, we need to rethink politics, work and participation, and finally learn to link our long-term ambitions for change with the pragmatic reformism of good governance —

a difficult balance to strike. However, it is possible if we heed the words of one of the finest intellectuals of the 20th century, Ernst Cassirer: ‘The great mission of the Utopia is to make room for the possible as opposed to a passive acquiescence in the present actual state of affairs. It is symbolic thought which overcomes the natural inertia of man and endows him with a new ability, the ability constantly to reshape his human universe.’

Therefore, bearing in mind Cassirer’s thinking alongside that of Lewis Mumford, we should note the distinction (which readers of this blog will already be familiar with) between a ‘utopia of escape’, which is the desire to build castles in the air, and a ‘utopia of reconstruction’, which is the commitment to imagining and implementing ambitious change. However, we must also think practically about good politics here and now.

How? Rebuilding trust is a general goal (we discussed this in blogs on 6 May and 7 October). To give the new generations a sense of purpose and the prospect of change. But in the meantime, make practical choices. We should make better use of the resources we have, namely women and young people, by guaranteeing them better access to the job market with career policies and incomes suited to their training, enabling them to transform their ambitions into enterprise and industriousness. We must change the cycle of Italy being abandoned by its most enterprising and active young people by offering growth opportunities and, at the same time, attracting new human resources from abroad, especially from the Mediterranean basin. We need to insist on education and bridge the knowledge and understanding gap (a third of Italians are ‘functionally illiterate’, meaning they cannot understand a written text of medium complexity or do basic maths). Finally, we have to commit adequate financial and intellectual resources to reintegrating a large portion of those NEETs we mentioned into civil coexistence and therefore responsible participation.

This is not a catalogue of good intentions, but rather an indication of the parts that make up a balanced plan for the development of Italy within Europe. It is a list of points that must be translated into government choices, investments (EU funds must be used wisely) and commitments involving not only political decision-makers, but also economic and cultural actors.

It is a difficult challenge, of course, but a key step for economic growth and, above all, for social balance.

A ‘citizenship collaboration’, according to Confindustria, at the end of a conference in Ortigia on Open Innovation and training, precisely to ‘highlight talent, knowledge, technology and productivity’ (Il Sole24Ore, 24 and 25 October). And The Young Entrepreneurs of Confindustria, chaired by Maria Anghileri, emphasise in their conferences the importance of opening up the company to new generations as a space in which to realise projects, ideas, ambitions and dreams. ‘The growing enterprise’ is their stated goal. Enterprise as an economic actor and a social catalyst.

From this point of view, the political choice is clear: the strategy we need is one of knowledge, innovation and training, particularly from an industrial policy perspective.

If our resources are limited, it is essential to invest in training our young people. This will enable them to reach their full potential. In the meantime, we must work to reverse the cycle of fearful closure in social microcosms and falling birth rates. We must invest in rebuilding trust and developing a positive vision for the future.

(photo Getty Images)