This Europe, so fragile, caught between a humiliating Trump administration in the US, a Russia under Putin that keeps it under threat of war, and a China under Xi JinPing that flatters it as a trade partner, but a second-class one…This Europe, so full of culture and tradition and yet uncertain and lost on the relevance of its values… This Europe, which has nurtured a vocabulary of grand words, yet all too often speaks with the wooden tongue of mediocre bureaucracy. How can we revive this Europe that has lost hope and forgotten how to dream?

We must go back to our roots and, drawing on our memory, rethink the reality of our democracy and plan a better, more solid future. With the courage and shrewdness of one who moves and engages in battles, both political and cultural, including in partibus infidelium (in the lands of the unbelievers).

Altiero Spinelli and Eugenio Colorni were just over thirty years old, and Ernesto Rossi just over forty, when they wrote the ‘Ventotene Manifesto’ in the harsh conditions of island confinement during the darkest period of fascist and Nazi domination of Europe. This manifesto was to become the cornerstone of European rebirth. And it was just after the horrors of World War II, when Thomas Mann published Moniti all’Europa, an anthology of political and civic essays in which he attempted to rebuild a sense of civilisation that would inspire a new era of coexistence and democracy.

So, it is precisely now, in these uncertain and dramatic times, as we walk on the edge of a precipice, along the narrow and slippery ridge that separates peace from war, (the President of the Republic, Sergio Mattarella, is right to evoke the spectre of 1914 as a danger to be avoided) that we must return to the foundations of our European identity. We must reread good books such as the ‘Manifesto’ and the works of Mann, and reflect on ‘words that make you live’ (Paul Éluard‘s inspiration in 1944, as previously mentioned in our blog post from 8 March).

Words such as: ‘You will win because you have brute force in abundance, but you will not convince. To convince, you need to persuade, and to persuade, you need something you lack: reason and justice in the struggle.’ These are the words of Miguel de Unamuno, a philosopher and writer, rector of the University of Salamanca, when, in 1936, he addressed a hostile audience of Falangists — the extreme right-wing supporters of General Francisco Franco — who were on the verge of winning the Spanish Civil War.

But is Europe convincing today? Can it convince its citizens of the importance and necessity of defending and reviving its values in the face of pitfalls posed by powerful and overbearing adversaries?

The fracture of the strong idea of the ‘West’ and ‘democracy’, alongside the new direction of government in the White House, has profoundly undermined confidence in the stability and future of an alliance that has been characterised by a shared commitment to democracy, freedom, and mutual interests, shaping the course of contemporary history from 1945 to the present day. Authoritarian systems and ‘illiberal democracies’ are finding easy acceptance in growing sectors of European public opinion, thanks to the polluting capabilities of social media and disinformation as an act of ‘hybrid warfare’, and under the illusion of easy and irresponsible shortcuts. This is a difficult, dangerous situation. As La Stampa (23 September) summarises: ‘Trump divides, Putin threatens: the double trap for Europe’.

Unfortunately, this crisis has deep roots. For some time now, we have been confronted with the phenomenon of ‘democracy’s discontent’, as described in the intriguing book of the same name by Michael J. Sandel (Feltrinelli), who teaches government theory at Harvard. He argues that we are living through a ‘dangerous political moment’ due to the mistakes made by Western democracies in uncritically embracing ‘finance-driven globalisation’, which has had negative consequences for workers and the middle classes — the social and cultural groups that form the backbone of liberal democracy. However, all is not lost: ‘In order to breathe new life into democracy, we must reconfigure the economy and empower citizens to take an active role in public life.’

It should be a ‘just’ economy that is also circular, sustainable and cohesive. It should combine productivity and social inclusion, as well as competitiveness and solidarity. The ideas of John Maynard Keynes and his most recent followers are back in the news, with Federico Caffè — Mario Draghi’s university teacher — calling for a Europe that is not marginal or submissive, but a key player in history. A ‘civil’ economy, also taking up the ideas of those who, from Naples (Antonio Genovesi, civil economy theorist) to Milan (the ‘good government’ analysed and proposed by the Verri brothers), in the most fertile and far-sighted period of the Enlightenment, attempted to put forward original ideas for political reforms and economic development.

And the Enlightenment is one of the finest achievements of European culture. It is an extraordinary and highly relevant lesson in civilisation that should never be forgotten. Cardinal of Turin Roberto Repole warns, ‘Today, Europe is experiencing a certain spiritual secularisation, but it has also betrayed the basic insight of the Enlightenment: that freedom entails assuming an ethical responsibility’ (La Stampa, 24 September). He argues, ‘We took the 20th-century acquisitions of peace, welfare and health for granted. We have passed on the memory of wars, but we no longer feel the need to reflect on the roots of peace that stemmed from the ethical consciousness of previous generations. We risk losing what we have because we have neglected to maintain it; we have not considered that peace and prosperity are not definitive, but a dynamic process.’ The Illuminists were aware of this, of the primacy of reason and its possible crisis, which remains to be answered. Even Leonardo Sciascia, the contemporary writer who was most aware of this lesson, knew this well. The title of his last book, published by Bompiani in 1989, was ‘For a Future Memory’: a synthesis of the duties of literature as creative work and civic responsibility. However, he added the warning, ‘If memory has a future’.

Enlightenment is the culture of yesterday reflected in today. So, looking to the future, what does Europe need to say today?

We are the only region in the world that is still capable of combining liberal democracy, a market economy and welfare in an extraordinary and original way. In other words, we embody freedom, economic and social innovation, and solidarity. This is a complex system of strong values and sophisticated governance and civic coexistence amidst diversity. And it is an area in which we must persist, even through courageous reforms, both institutional — such as ending unanimity for decisions by the 27 EU countries, a trend which is already underway anyway — and political, such as common investments and efficient, effective public spending on security, sustainable development and knowledge.

We must do it quickly and we must do it well. It is also vital to raise awareness among Europeans of the choices to be made and their consequences, and to encourage them to consider the values involved.

Reconstruct a convincing, persuasive narrative of Europe’s values, strengths and necessity. As a democracy, a paradigm of balanced development and a destiny. Persuade, as Unamuno said, and as the best European politicians (from the ‘founding fathers’ to Kohl, Delors and Mitterrand) have done until now. And revive cultures and rules as an alternative to the primacy of force, which denies civilisation and relations inspired by the rule of law.

How? Here is another point to consider in relation to the crisis: the language of Europe. Certainly not the bureaucratic, cold, distant and complicated language of verbose treaties and obscure regulations. Nor the long-winded, formal and icy language of the EU Constitution, which was approved by the European Parliament in 2004 but never came into force as it was not ratified by some member states. This constitution has an enormous 448 articles, which is even more than the 139 articles (plus 18 articles of ‘transitional and final provisions’) of the Italian constitution, the 146 articles of the German constitution, and the 89 articles (plus a preamble) of the French constitution.

If anything, the language of literature and art. As Antonio Spadaro explains in la Repubblica (24 September), ‘Europe is a great novel. Beyond treaties, which are insufficient, it must be experienced as an epic narrative, following in the footsteps of Mann, Musil, Balzac, Flaubert, Cervantes, and contemporary novelists such as Javier Cercas’, as well as poets, philosophers, and historians who have depicted its controversies and connections throughout history. Because ‘telling the story like this, like a novel, also means going through the conflicts and making us experience them, rather than denying them; inhabiting contradictions rather than evading them; remembering the wounds rather than concealing them, and thus beginning to heal them; and not erasing the clash, but going through it’.

Europe as life and destiny, an awareness of roots and a vision of the future. Not as a region to impose authoritarian thinking, which is too violent and infinitely poor, compared to the rich complexity of our history, which deserves to have a future.

A project demonstrating courageous political choices, firmness when confronting our necessary ally, the US, and effective management of those who detest Europe and all it stands for — economically, spiritually, culturally and morally — can help reacquaint citizens and, perhaps more importantly, new generations with Europe.

A Europe we can trust: strengthening what is already there. This is confirmed by the 2025 European Sentiment Compass, which was drawn up in cooperation with the European Council on Foreign Relations and cited by two European scholars, André Wilkens and Paweł Zerka, in Il Foglio on 26 September. The study argues that European sentiment has been strengthened and shaped by the pandemic, as Europe tackled the crisis and its aftermath with a spirit of cooperation in terms of vaccines and health responses, as well as economic and planning intelligence, with Next Generation EU funding. This was then reinforced by concrete and active solidarity in response to Russia’s attack on Ukraine. And trust in the EU is also at its highest since 2007: ‘In almost all Member States, the majority of citizens feel connected to Europe, identify as EU citizens, and are optimistic about the Union’s future. More and more people see Europe as not only an economic project, but also a community of security and shared destiny.’

Even if media reports and widespread political stances seem to suggest otherwise. It is necessary to investigate and understand this better, but certainly, decisive action is needed to build, rebuild or strengthen trust. The challenge is political, especially today, when it comes to security. But it is also, and above all, cultural, ethical and civil. And on these fronts, Europe still has good cards to play.

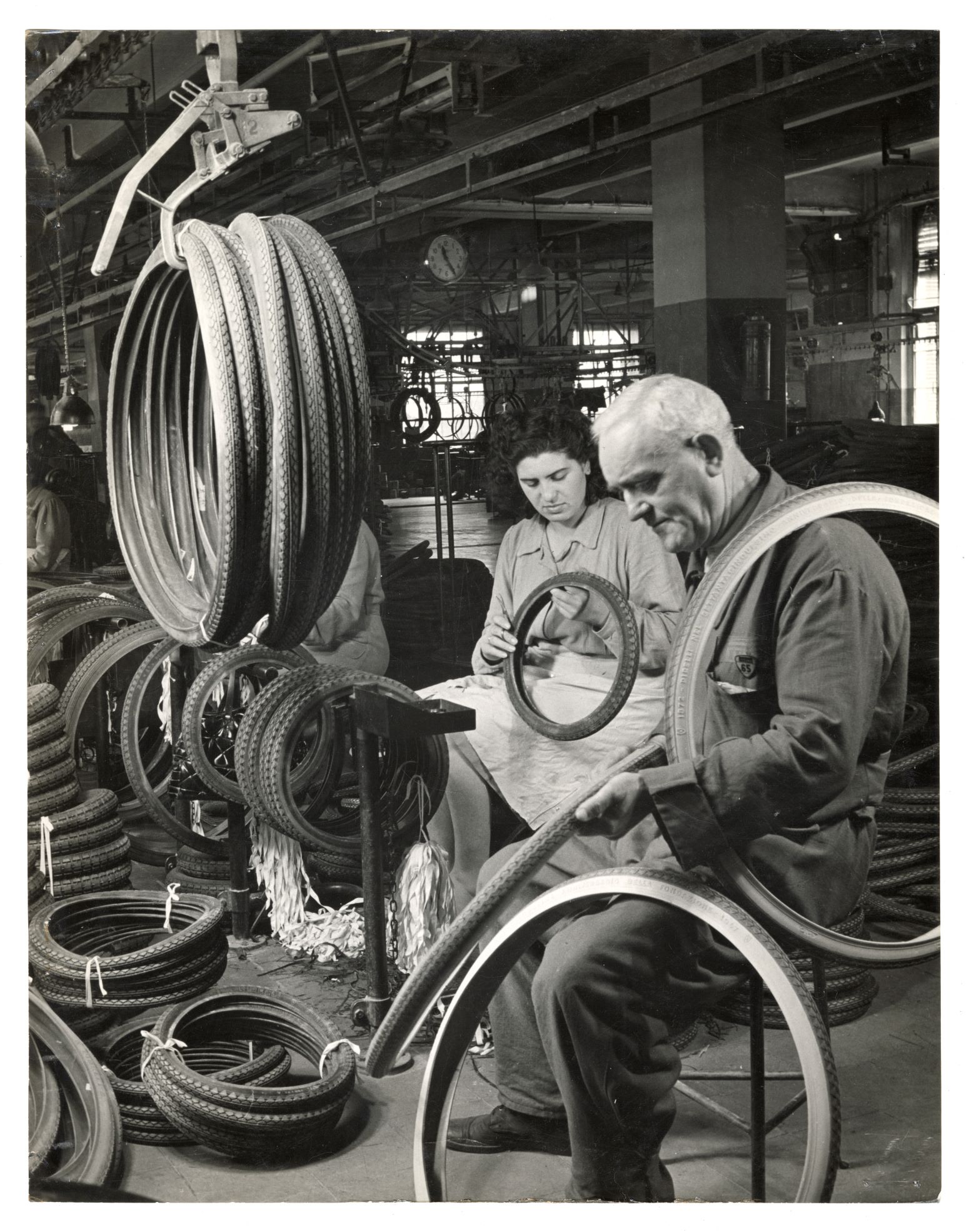

Photo Getty Images

This Europe, so fragile, caught between a humiliating Trump administration in the US, a Russia under Putin that keeps it under threat of war, and a China under Xi JinPing that flatters it as a trade partner, but a second-class one…This Europe, so full of culture and tradition and yet uncertain and lost on the relevance of its values… This Europe, which has nurtured a vocabulary of grand words, yet all too often speaks with the wooden tongue of mediocre bureaucracy. How can we revive this Europe that has lost hope and forgotten how to dream?

We must go back to our roots and, drawing on our memory, rethink the reality of our democracy and plan a better, more solid future. With the courage and shrewdness of one who moves and engages in battles, both political and cultural, including in partibus infidelium (in the lands of the unbelievers).

Altiero Spinelli and Eugenio Colorni were just over thirty years old, and Ernesto Rossi just over forty, when they wrote the ‘Ventotene Manifesto’ in the harsh conditions of island confinement during the darkest period of fascist and Nazi domination of Europe. This manifesto was to become the cornerstone of European rebirth. And it was just after the horrors of World War II, when Thomas Mann published Moniti all’Europa, an anthology of political and civic essays in which he attempted to rebuild a sense of civilisation that would inspire a new era of coexistence and democracy.

So, it is precisely now, in these uncertain and dramatic times, as we walk on the edge of a precipice, along the narrow and slippery ridge that separates peace from war, (the President of the Republic, Sergio Mattarella, is right to evoke the spectre of 1914 as a danger to be avoided) that we must return to the foundations of our European identity. We must reread good books such as the ‘Manifesto’ and the works of Mann, and reflect on ‘words that make you live’ (Paul Éluard‘s inspiration in 1944, as previously mentioned in our blog post from 8 March).

Words such as: ‘You will win because you have brute force in abundance, but you will not convince. To convince, you need to persuade, and to persuade, you need something you lack: reason and justice in the struggle.’ These are the words of Miguel de Unamuno, a philosopher and writer, rector of the University of Salamanca, when, in 1936, he addressed a hostile audience of Falangists — the extreme right-wing supporters of General Francisco Franco — who were on the verge of winning the Spanish Civil War.

But is Europe convincing today? Can it convince its citizens of the importance and necessity of defending and reviving its values in the face of pitfalls posed by powerful and overbearing adversaries?

The fracture of the strong idea of the ‘West’ and ‘democracy’, alongside the new direction of government in the White House, has profoundly undermined confidence in the stability and future of an alliance that has been characterised by a shared commitment to democracy, freedom, and mutual interests, shaping the course of contemporary history from 1945 to the present day. Authoritarian systems and ‘illiberal democracies’ are finding easy acceptance in growing sectors of European public opinion, thanks to the polluting capabilities of social media and disinformation as an act of ‘hybrid warfare’, and under the illusion of easy and irresponsible shortcuts. This is a difficult, dangerous situation. As La Stampa (23 September) summarises: ‘Trump divides, Putin threatens: the double trap for Europe’.

Unfortunately, this crisis has deep roots. For some time now, we have been confronted with the phenomenon of ‘democracy’s discontent’, as described in the intriguing book of the same name by Michael J. Sandel (Feltrinelli), who teaches government theory at Harvard. He argues that we are living through a ‘dangerous political moment’ due to the mistakes made by Western democracies in uncritically embracing ‘finance-driven globalisation’, which has had negative consequences for workers and the middle classes — the social and cultural groups that form the backbone of liberal democracy. However, all is not lost: ‘In order to breathe new life into democracy, we must reconfigure the economy and empower citizens to take an active role in public life.’

It should be a ‘just’ economy that is also circular, sustainable and cohesive. It should combine productivity and social inclusion, as well as competitiveness and solidarity. The ideas of John Maynard Keynes and his most recent followers are back in the news, with Federico Caffè — Mario Draghi’s university teacher — calling for a Europe that is not marginal or submissive, but a key player in history. A ‘civil’ economy, also taking up the ideas of those who, from Naples (Antonio Genovesi, civil economy theorist) to Milan (the ‘good government’ analysed and proposed by the Verri brothers), in the most fertile and far-sighted period of the Enlightenment, attempted to put forward original ideas for political reforms and economic development.

And the Enlightenment is one of the finest achievements of European culture. It is an extraordinary and highly relevant lesson in civilisation that should never be forgotten. Cardinal of Turin Roberto Repole warns, ‘Today, Europe is experiencing a certain spiritual secularisation, but it has also betrayed the basic insight of the Enlightenment: that freedom entails assuming an ethical responsibility’ (La Stampa, 24 September). He argues, ‘We took the 20th-century acquisitions of peace, welfare and health for granted. We have passed on the memory of wars, but we no longer feel the need to reflect on the roots of peace that stemmed from the ethical consciousness of previous generations. We risk losing what we have because we have neglected to maintain it; we have not considered that peace and prosperity are not definitive, but a dynamic process.’ The Illuminists were aware of this, of the primacy of reason and its possible crisis, which remains to be answered. Even Leonardo Sciascia, the contemporary writer who was most aware of this lesson, knew this well. The title of his last book, published by Bompiani in 1989, was ‘For a Future Memory’: a synthesis of the duties of literature as creative work and civic responsibility. However, he added the warning, ‘If memory has a future’.

Enlightenment is the culture of yesterday reflected in today. So, looking to the future, what does Europe need to say today?

We are the only region in the world that is still capable of combining liberal democracy, a market economy and welfare in an extraordinary and original way. In other words, we embody freedom, economic and social innovation, and solidarity. This is a complex system of strong values and sophisticated governance and civic coexistence amidst diversity. And it is an area in which we must persist, even through courageous reforms, both institutional — such as ending unanimity for decisions by the 27 EU countries, a trend which is already underway anyway — and political, such as common investments and efficient, effective public spending on security, sustainable development and knowledge.

We must do it quickly and we must do it well. It is also vital to raise awareness among Europeans of the choices to be made and their consequences, and to encourage them to consider the values involved.

Reconstruct a convincing, persuasive narrative of Europe’s values, strengths and necessity. As a democracy, a paradigm of balanced development and a destiny. Persuade, as Unamuno said, and as the best European politicians (from the ‘founding fathers’ to Kohl, Delors and Mitterrand) have done until now. And revive cultures and rules as an alternative to the primacy of force, which denies civilisation and relations inspired by the rule of law.

How? Here is another point to consider in relation to the crisis: the language of Europe. Certainly not the bureaucratic, cold, distant and complicated language of verbose treaties and obscure regulations. Nor the long-winded, formal and icy language of the EU Constitution, which was approved by the European Parliament in 2004 but never came into force as it was not ratified by some member states. This constitution has an enormous 448 articles, which is even more than the 139 articles (plus 18 articles of ‘transitional and final provisions’) of the Italian constitution, the 146 articles of the German constitution, and the 89 articles (plus a preamble) of the French constitution.

If anything, the language of literature and art. As Antonio Spadaro explains in la Repubblica (24 September), ‘Europe is a great novel. Beyond treaties, which are insufficient, it must be experienced as an epic narrative, following in the footsteps of Mann, Musil, Balzac, Flaubert, Cervantes, and contemporary novelists such as Javier Cercas’, as well as poets, philosophers, and historians who have depicted its controversies and connections throughout history. Because ‘telling the story like this, like a novel, also means going through the conflicts and making us experience them, rather than denying them; inhabiting contradictions rather than evading them; remembering the wounds rather than concealing them, and thus beginning to heal them; and not erasing the clash, but going through it’.

Europe as life and destiny, an awareness of roots and a vision of the future. Not as a region to impose authoritarian thinking, which is too violent and infinitely poor, compared to the rich complexity of our history, which deserves to have a future.

A project demonstrating courageous political choices, firmness when confronting our necessary ally, the US, and effective management of those who detest Europe and all it stands for — economically, spiritually, culturally and morally — can help reacquaint citizens and, perhaps more importantly, new generations with Europe.

A Europe we can trust: strengthening what is already there. This is confirmed by the 2025 European Sentiment Compass, which was drawn up in cooperation with the European Council on Foreign Relations and cited by two European scholars, André Wilkens and Paweł Zerka, in Il Foglio on 26 September. The study argues that European sentiment has been strengthened and shaped by the pandemic, as Europe tackled the crisis and its aftermath with a spirit of cooperation in terms of vaccines and health responses, as well as economic and planning intelligence, with Next Generation EU funding. This was then reinforced by concrete and active solidarity in response to Russia’s attack on Ukraine. And trust in the EU is also at its highest since 2007: ‘In almost all Member States, the majority of citizens feel connected to Europe, identify as EU citizens, and are optimistic about the Union’s future. More and more people see Europe as not only an economic project, but also a community of security and shared destiny.’

Even if media reports and widespread political stances seem to suggest otherwise. It is necessary to investigate and understand this better, but certainly, decisive action is needed to build, rebuild or strengthen trust. The challenge is political, especially today, when it comes to security. But it is also, and above all, cultural, ethical and civil. And on these fronts, Europe still has good cards to play.

Photo Getty Images