“Advertising Architecture” at Trade Fairs in the 1950s

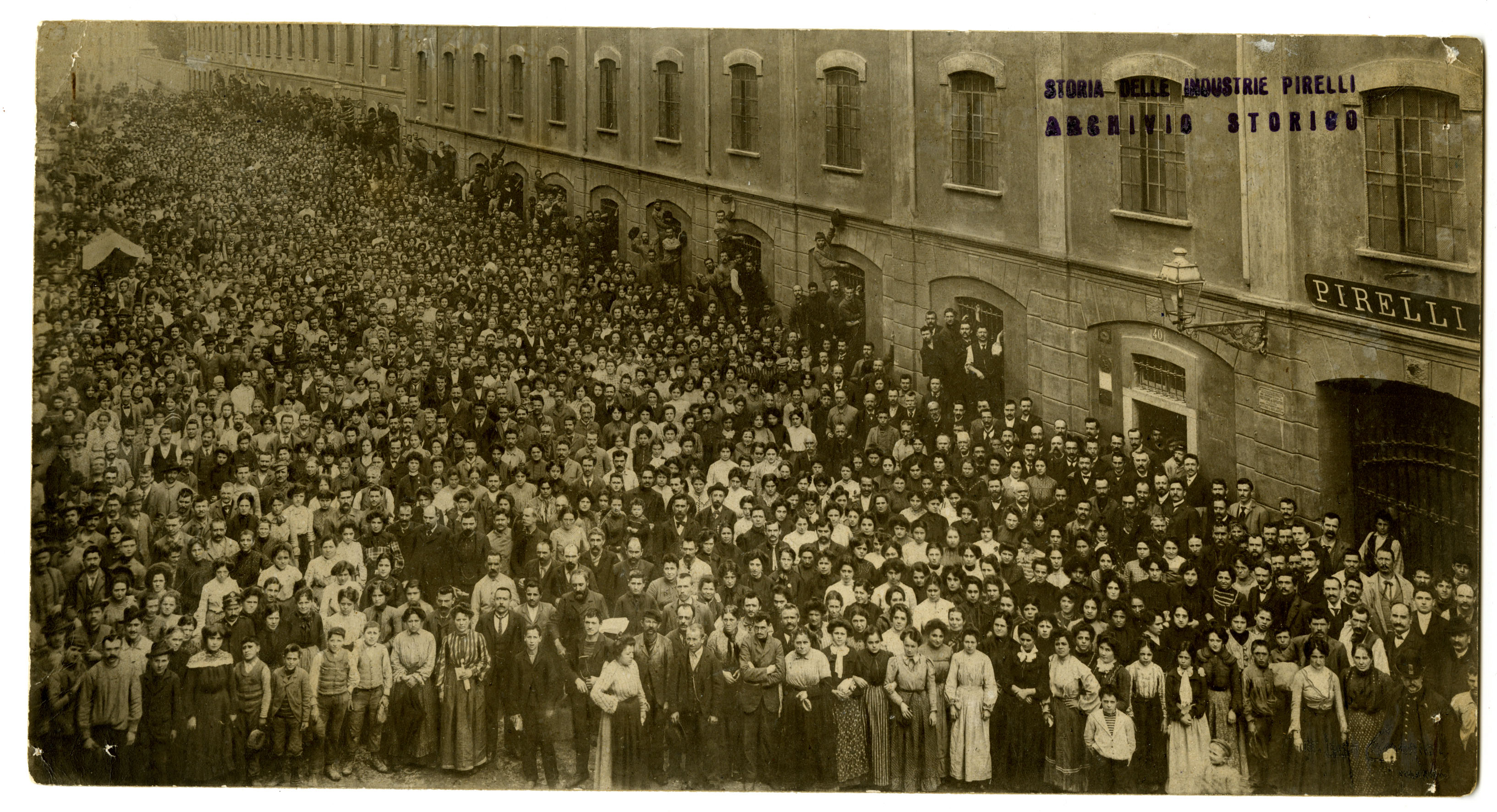

Pirelli has been presenting its products at exhibitions and trade fairs ever since it was founded. After the National Exhibition in Milan in 1881, when the company has not yet reached the age of ten, it began appearing at trade fairs across the world, from Paris (1900) to Osaka (1903), to Saint Louis (1904) and Buenos Aires (1910). There was no shortage of experimentation in terms of display installations at these early twentieth-century fairs – such as the blown-up poster photo of workers leaving the factory, which was created by Luca Comerio for the 1906 Sempione fair – but it was in the 1950s that great names in architecture and graphic design came up with truly innovative solutions for trade-fair architecture. With Leonardo Sinisgalli as a consultant, Pirelli resumed its advertising activity in all its various forms in 1948. Trade fairs played an important part in presenting the company’s numerous products at an international level, as can be seen in the many photographs that are preserved in our Historical Archive and that are now available online. One of the first major post-war trade fairs in which Pirelli took part with an innovative stand was the 1951 Fiera Campionaria in Milan, which once again opened its doors after the reconstruction following the 1943 bombing raids. The concept was most likely by Sinisgalli, but the architectural design of the stand was the work of Luigi Gargantini, who created a sort of “advertising castle”, as the magazine Domus referred to it in its July-August 1951 issue: an installation with no products on display but only the advertisements created by Pirelli throughout its long history, reproduced on cubes and polyhedrons fastened to poles inside a structure that was open on four sides. “Rarely has a product of modern life been honoured with such an elegant display”, wrote Vittorio Bonicelli in his article “Architettura pubblicitaria“ [Advertising Architecture] in Pirelli magazine, “but that is not really the most important aspect […]: what matters most is the balance of solids and voids, and how space, light and colour have their own very precise, unalterable place. This is the essence of style,” concludes Bonicelli.

In the 1950s, when the “Propaganda Pirelli” department was taken over by Arrigo Castellani after Leonardo Sinisgalli had stepped down, the phenomenon of trade fairs expanded dramatically, both in terms of the number of visitors and as places for architectural experimentation. The displays became increasingly spectacular, in order to satisfy the public’s desire for “part science fiction and part funfair” as Francesco Mafera put it in his article for Pirelli magazine, Settantacinque fiere in un anno [Seventy-five trade fairs in one year] in which he wondered how appropriate the magnificence and cost of some exhibition stands had become in those years. In the article, he mentions the structure designed by the architect Roberto Menghi for the 1955 Fiera Campionaria as an example of a “sensational” display: a raised swimming pool, the outcome of a partnership between Pirelli and the organising committee of the fair. The pool was in the form of a reinforced concrete cage with glass walls, placed on ten pedestals, in which the divers of the Pirelli Sports Group demonstrated the company’s products for the sea. One of the most spectacular pavilions was set up by Pirelli at the Fiera del Levante in Bari that same year: it was an authentic work of engineering, once again entrusted to Luigi Gargantini with the supervision of the engineer Giuseppe Valtolina. An enormous tractor tyre, 16 metres in diameter and weighing 20 tons, was balanced on a cantilevered support over the main street of the fair, towering above the public as they walked beneath it, conveying an idea of the power of Pirelli’s contribution to the development of the South of Italy. Considerable technical measures were required both to keep the structure in equilibrium and to withstand the wind, as well as to obtain the extraordinary size of the wheel. An article was written about this display too, and published in Pirelli magazine, extolling its architectural value, which was given by “the contrast between the simple, linear structures of the support […] and the inflated sculptural roundness of the tyre with the very pronounced swirl of its tread.” Pirelli products for agriculture were shown around the structure, in a display designed by Pino Tovaglia, with “a decorative play of great sculptural effect”.

There are also some examples of installations from these years that are less spectacular but still remarkable for the high quality of their design. This was the case at the 1956 Bicycle and Motorcycle Fair, where Pirelli showed its products in a display designed by Franco Albini and Franca Helg, with the contribution of Pino Tovaglia. The stand retraced the history of the bicycle, with a display of historical items inside a structure that recalled the shape of a large wheel. A pillar at the centre held up four radial frames with graphics by Tovaglia, beneath which were the tyres and accessories for bicycles and motorcycles that had made the history of two-wheeled transport. The display was a fine example of the rationalism and discipline typical of Franco Albini, and the stand was hailed by the magazine Ciclismo as “the greatest, most moving and most poetic ode to the bicycle that any firm, large or small (and this is a very large, unattainable one), has ever devoted to the queen of the road”.

Those involved in the design of trade-fair stands in these years and, later, in the 1960s, also included Erberto Carboni, Bruno Munari, and Bob Noorda, as well as Renato Guttuso, who in 1961 created the extraordinary mosaic dedicated to scientific research. The work was shown in the pavilion designed for Pirelli by Franco Albini and Franca Helg for Expo 61 in Turin, and is now on display at the Pirelli Foundation.

Pirelli has been presenting its products at exhibitions and trade fairs ever since it was founded. After the National Exhibition in Milan in 1881, when the company has not yet reached the age of ten, it began appearing at trade fairs across the world, from Paris (1900) to Osaka (1903), to Saint Louis (1904) and Buenos Aires (1910). There was no shortage of experimentation in terms of display installations at these early twentieth-century fairs – such as the blown-up poster photo of workers leaving the factory, which was created by Luca Comerio for the 1906 Sempione fair – but it was in the 1950s that great names in architecture and graphic design came up with truly innovative solutions for trade-fair architecture. With Leonardo Sinisgalli as a consultant, Pirelli resumed its advertising activity in all its various forms in 1948. Trade fairs played an important part in presenting the company’s numerous products at an international level, as can be seen in the many photographs that are preserved in our Historical Archive and that are now available online. One of the first major post-war trade fairs in which Pirelli took part with an innovative stand was the 1951 Fiera Campionaria in Milan, which once again opened its doors after the reconstruction following the 1943 bombing raids. The concept was most likely by Sinisgalli, but the architectural design of the stand was the work of Luigi Gargantini, who created a sort of “advertising castle”, as the magazine Domus referred to it in its July-August 1951 issue: an installation with no products on display but only the advertisements created by Pirelli throughout its long history, reproduced on cubes and polyhedrons fastened to poles inside a structure that was open on four sides. “Rarely has a product of modern life been honoured with such an elegant display”, wrote Vittorio Bonicelli in his article “Architettura pubblicitaria“ [Advertising Architecture] in Pirelli magazine, “but that is not really the most important aspect […]: what matters most is the balance of solids and voids, and how space, light and colour have their own very precise, unalterable place. This is the essence of style,” concludes Bonicelli.

In the 1950s, when the “Propaganda Pirelli” department was taken over by Arrigo Castellani after Leonardo Sinisgalli had stepped down, the phenomenon of trade fairs expanded dramatically, both in terms of the number of visitors and as places for architectural experimentation. The displays became increasingly spectacular, in order to satisfy the public’s desire for “part science fiction and part funfair” as Francesco Mafera put it in his article for Pirelli magazine, Settantacinque fiere in un anno [Seventy-five trade fairs in one year] in which he wondered how appropriate the magnificence and cost of some exhibition stands had become in those years. In the article, he mentions the structure designed by the architect Roberto Menghi for the 1955 Fiera Campionaria as an example of a “sensational” display: a raised swimming pool, the outcome of a partnership between Pirelli and the organising committee of the fair. The pool was in the form of a reinforced concrete cage with glass walls, placed on ten pedestals, in which the divers of the Pirelli Sports Group demonstrated the company’s products for the sea. One of the most spectacular pavilions was set up by Pirelli at the Fiera del Levante in Bari that same year: it was an authentic work of engineering, once again entrusted to Luigi Gargantini with the supervision of the engineer Giuseppe Valtolina. An enormous tractor tyre, 16 metres in diameter and weighing 20 tons, was balanced on a cantilevered support over the main street of the fair, towering above the public as they walked beneath it, conveying an idea of the power of Pirelli’s contribution to the development of the South of Italy. Considerable technical measures were required both to keep the structure in equilibrium and to withstand the wind, as well as to obtain the extraordinary size of the wheel. An article was written about this display too, and published in Pirelli magazine, extolling its architectural value, which was given by “the contrast between the simple, linear structures of the support […] and the inflated sculptural roundness of the tyre with the very pronounced swirl of its tread.” Pirelli products for agriculture were shown around the structure, in a display designed by Pino Tovaglia, with “a decorative play of great sculptural effect”.

There are also some examples of installations from these years that are less spectacular but still remarkable for the high quality of their design. This was the case at the 1956 Bicycle and Motorcycle Fair, where Pirelli showed its products in a display designed by Franco Albini and Franca Helg, with the contribution of Pino Tovaglia. The stand retraced the history of the bicycle, with a display of historical items inside a structure that recalled the shape of a large wheel. A pillar at the centre held up four radial frames with graphics by Tovaglia, beneath which were the tyres and accessories for bicycles and motorcycles that had made the history of two-wheeled transport. The display was a fine example of the rationalism and discipline typical of Franco Albini, and the stand was hailed by the magazine Ciclismo as “the greatest, most moving and most poetic ode to the bicycle that any firm, large or small (and this is a very large, unattainable one), has ever devoted to the queen of the road”.

Those involved in the design of trade-fair stands in these years and, later, in the 1960s, also included Erberto Carboni, Bruno Munari, and Bob Noorda, as well as Renato Guttuso, who in 1961 created the extraordinary mosaic dedicated to scientific research. The work was shown in the pavilion designed for Pirelli by Franco Albini and Franca Helg for Expo 61 in Turin, and is now on display at the Pirelli Foundation.