Like a City

Milan and Pirelli: centres of cultural production and key players in the latest chapter in the “Pirelli, a City and a Vision” series. Documents and testimonies from our Historical Archive trace the story of a company that has long placed the promotion of art and culture at the heart of its policy

From the post-war years to the 1960s, Italy’s major companies were not just hubs of manufacturing for they were also cultural powerhouses. They worked with writers, intellectuals and artists to create business models that would combine scientific and technical expertise with humanistic ideas, while also helping to bring about cultural progress in society. Among these, Pirelli was going through a particularly prolific period of what might be called “industrial humanism”, inspired by the vibrant cultural life of Milan. This was a city that, in those same years, was emerging as an exciting international centre for artists and thinkers.

One year, in particular, stands out as a beacon in this story: 1947. This was the year when the Piccolo Teatro della Città di Milano was founded. It was to be a public theatre “for everyone”, and was the brainchild of Giorgio Strehler, Paolo Grassi and Nina Vinchi with the support of the City of Milan. The year also marked the launch of the Pirelli Cultural Centre, a company club run by Silvestro Severgnini, a friend of Paolo Grassi. Its aim was to offer employees access to music, theatre, the visual arts, cinema and literature.

As Severgnini himself put it in Pirelli magazine no. 1 of 1951, it adopted “a new and pretty successful formula to increase workers’ interest in culture”. The company “provides the means so that its employees, if they feel so inclined, can take part in the liveliest and most vital expressions of knowledge”

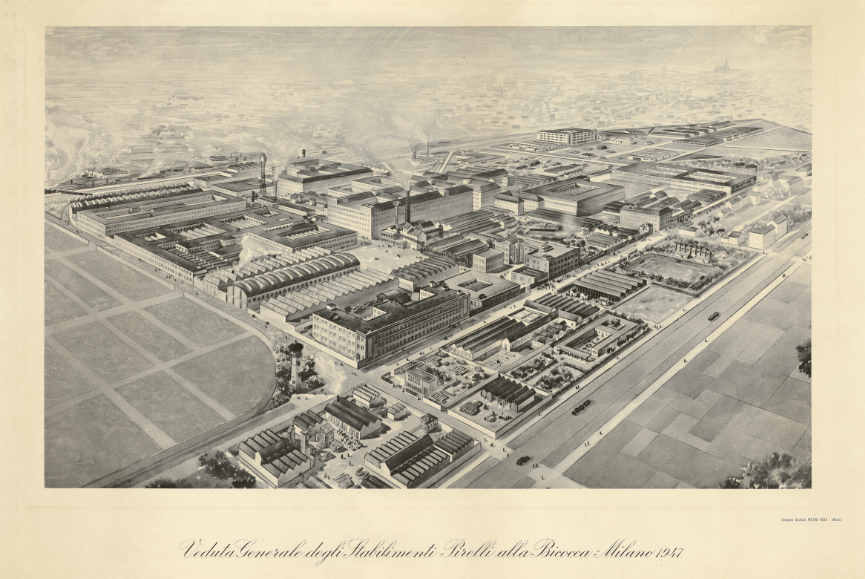

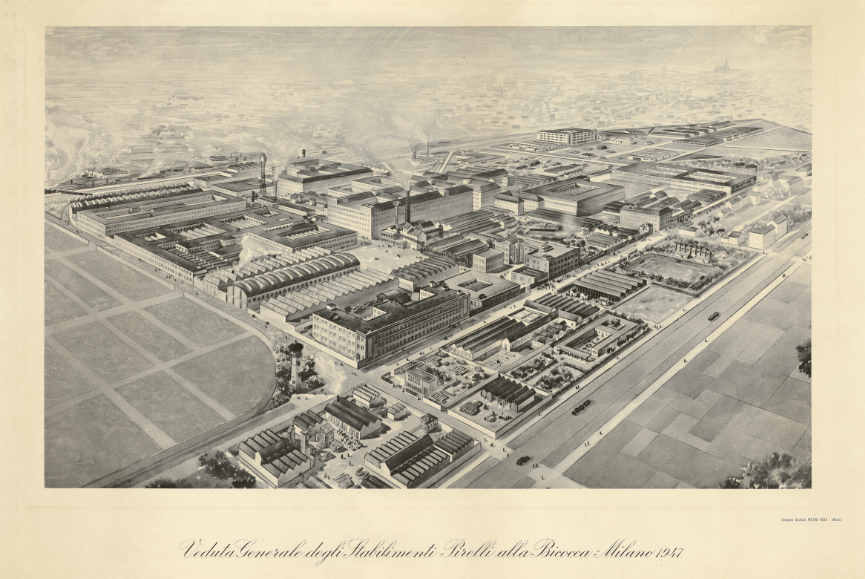

A natural partnership was soon formed between the Piccolo Teatro and the Pirelli Cultural Centre, symbolising a common objective adopted by both the city and the company. After all, could a company that now sprawled across a million square metres not be considered as a city in its own right?

“Also the worker shall not live by bread alone,” read a 1947 headline in the company newsletter, which was produced by Pirelli workers in the aftermath of the war. And it continued: “If you wish to calm the workers’ spirits […] you must bring them closer to art, to an art that is intelligible and life-giving […]. A new cultural initiative has been launched under the auspices of the Mayor of Milan in order to achieve this. A low-cost season ticket is all it takes to access this theatre (and our Cultural Centre itself has already signed up to it).”

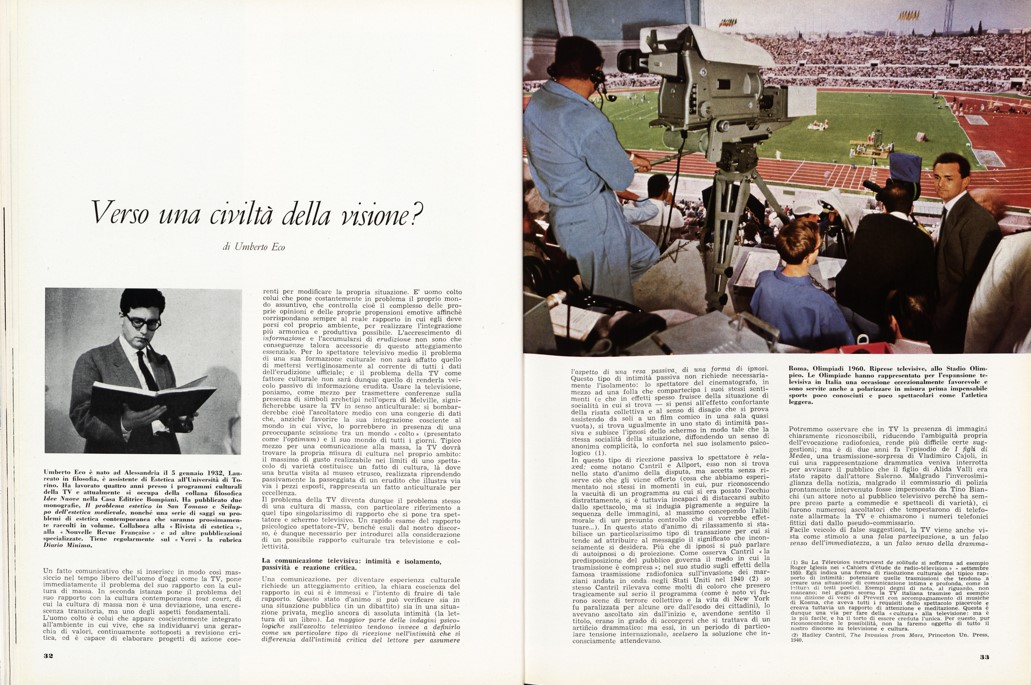

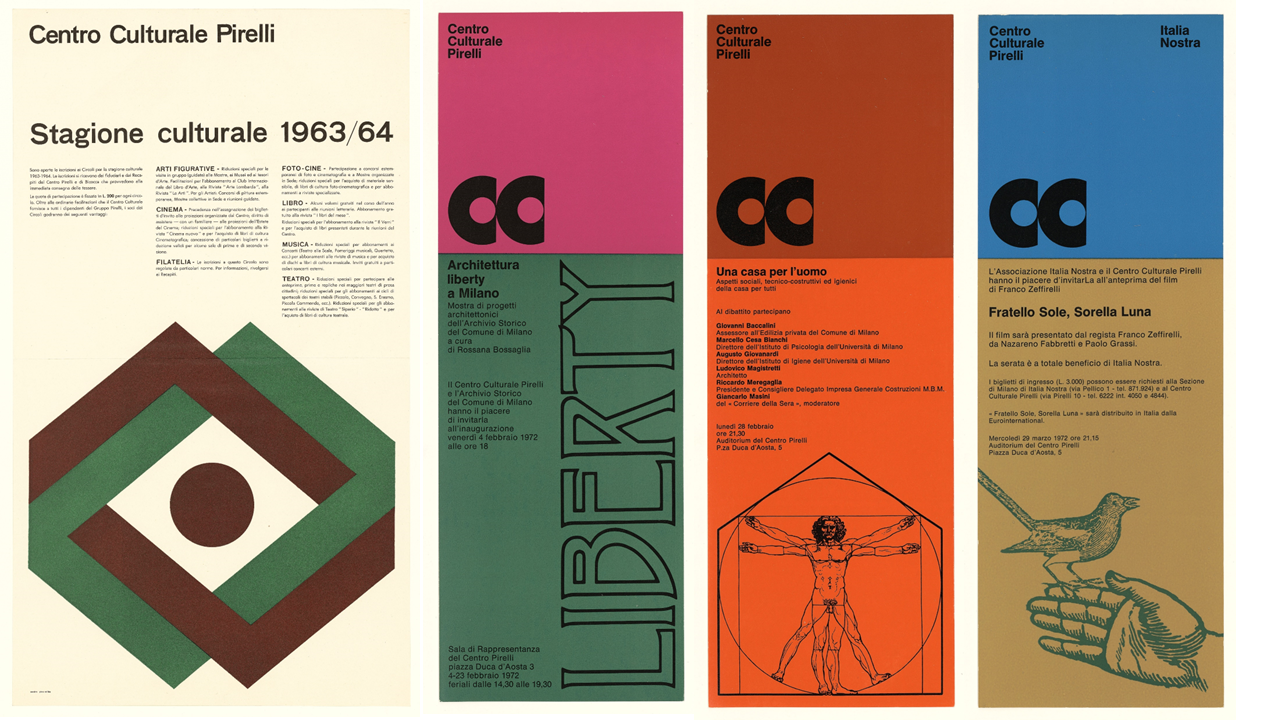

As the years went by, the Cultural Centre had more and more to offer, and Pirelli forged ties with other cultural institutions in Milan, such as La Scala, the Pomeriggi Musicali, and the Teatro del Popolo. In 1952 the Centre registered 12,495 attendances in the city’s opera and concert season, becoming “a notable presence in the cultural life of the city due to its size “ (Pirelli magazine, La fabbrica è aperta ai movimenti della cultura (“The factory is open to cultural movements”) and, from 1960, it enjoyed a prestigious space of its own. This was the auditorium in the Pirelli Tower, after it abandoned the premises of the “Ritrovo” in the old Brusada factory which escaped the bombings of 1943. This marked the beginning of a new chapter of cultural activities, with concerts, lectures, readings, screenings and presentations with prominent guests, including political and academic personalities, as well as writers, poets, and journalists, such as Italo Calvino, Umberto Eco, Guido Lopez, Salvatore Quasimodo and Mario Soldati.

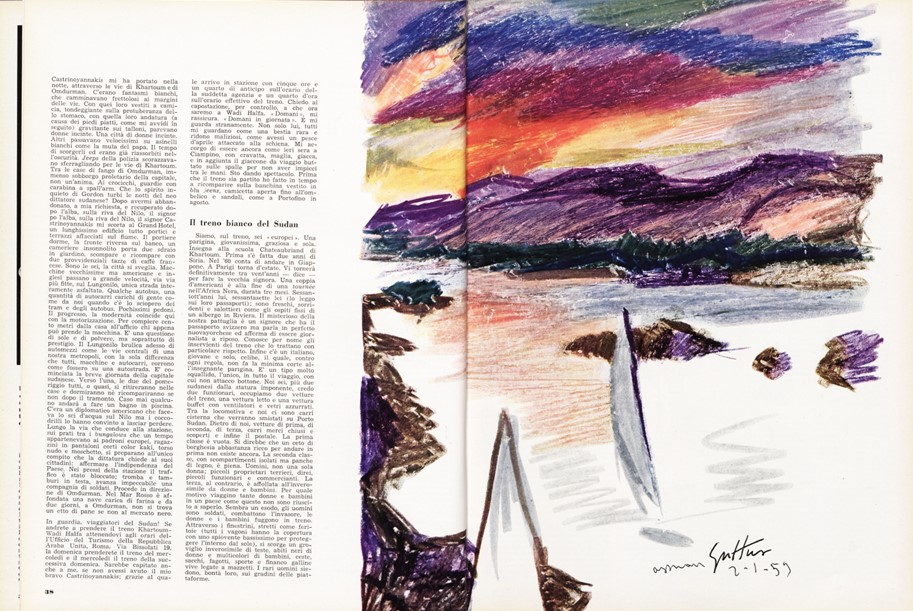

At the same time, one of the country’s most advanced cultural forums was taking shape within the pages of Pirelli. Rivista d’informazione e di tecnica. Published from 1948 to 1972, generally bi-monthly and available at newsstands, Pirelli magazine bridged the gap between scientific-technical and humanistic culture. Its articles looked at issues concerning industrial production, science and technology alongside reflections on art, architecture, sociology, economics, urbanism and literature. The magazine had a wide range of illustrious contributors: Giulio Carlo Argan, Dino Buzzati, Camilla Cederna, Gillo Dorfles, Arrigo Levi, Eugenio Montale, Fernanda Pivano, Franco Quadri, Alberto Ronchey, Elio Vittorini and dozens of others. Its striking visuals were enriched by splendid photographic essays by masters such as Arno Hammacher, Pepi Merisio, Ugo Mulas, Federico Patellani, Fulvio Roiter, Enzo Sellerio, and illustrations by artists including Renato Guttuso, Riccardo Manzi and Alessandro Mendini.

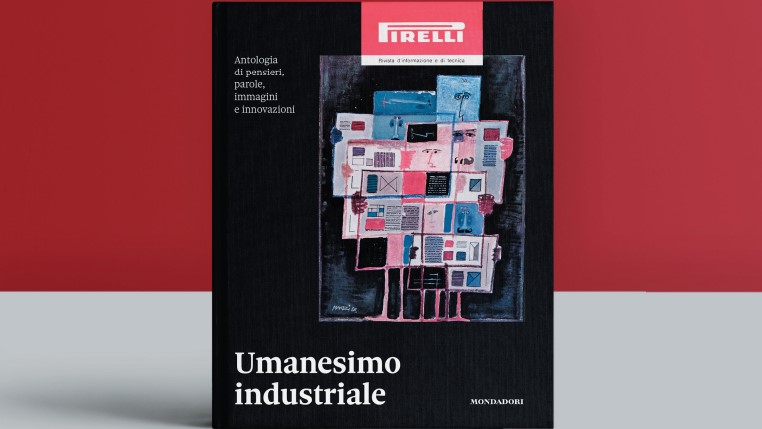

The legacy of Pirelli magazine is preserved in the volume Industrial Humanism. An Anthology of Thoughts, Words, Images and Innovations, edited by the Pirelli Foundation and published by Mondadori in 2019. All 131 issues, along with a photographic archive comprising 6,000 images—3,500 published and 2,500 unprinted—are now kept in our Historical Archive. The collection includes the very first issue, with an editorial by Alberto Pirelli, who explains the original and authentic purpose of the publication: “This industry uses an enormous variety of materials […] it relies on the most diverse array of machines and tools […] So many ways to contribute to the evolution of modern life […] But if, in this magazine, we may at times allow ourselves to rise a little higher, we shall do so in the belief that every contribution to the mechanised world needs to come about within the broader framework of life’s highest social and cultural values.“

Milan and Pirelli: centres of cultural production and key players in the latest chapter in the “Pirelli, a City and a Vision” series. Documents and testimonies from our Historical Archive trace the story of a company that has long placed the promotion of art and culture at the heart of its policy

From the post-war years to the 1960s, Italy’s major companies were not just hubs of manufacturing for they were also cultural powerhouses. They worked with writers, intellectuals and artists to create business models that would combine scientific and technical expertise with humanistic ideas, while also helping to bring about cultural progress in society. Among these, Pirelli was going through a particularly prolific period of what might be called “industrial humanism”, inspired by the vibrant cultural life of Milan. This was a city that, in those same years, was emerging as an exciting international centre for artists and thinkers.

One year, in particular, stands out as a beacon in this story: 1947. This was the year when the Piccolo Teatro della Città di Milano was founded. It was to be a public theatre “for everyone”, and was the brainchild of Giorgio Strehler, Paolo Grassi and Nina Vinchi with the support of the City of Milan. The year also marked the launch of the Pirelli Cultural Centre, a company club run by Silvestro Severgnini, a friend of Paolo Grassi. Its aim was to offer employees access to music, theatre, the visual arts, cinema and literature.

As Severgnini himself put it in Pirelli magazine no. 1 of 1951, it adopted “a new and pretty successful formula to increase workers’ interest in culture”. The company “provides the means so that its employees, if they feel so inclined, can take part in the liveliest and most vital expressions of knowledge”

A natural partnership was soon formed between the Piccolo Teatro and the Pirelli Cultural Centre, symbolising a common objective adopted by both the city and the company. After all, could a company that now sprawled across a million square metres not be considered as a city in its own right?

“Also the worker shall not live by bread alone,” read a 1947 headline in the company newsletter, which was produced by Pirelli workers in the aftermath of the war. And it continued: “If you wish to calm the workers’ spirits […] you must bring them closer to art, to an art that is intelligible and life-giving […]. A new cultural initiative has been launched under the auspices of the Mayor of Milan in order to achieve this. A low-cost season ticket is all it takes to access this theatre (and our Cultural Centre itself has already signed up to it).”

As the years went by, the Cultural Centre had more and more to offer, and Pirelli forged ties with other cultural institutions in Milan, such as La Scala, the Pomeriggi Musicali, and the Teatro del Popolo. In 1952 the Centre registered 12,495 attendances in the city’s opera and concert season, becoming “a notable presence in the cultural life of the city due to its size “ (Pirelli magazine, La fabbrica è aperta ai movimenti della cultura (“The factory is open to cultural movements”) and, from 1960, it enjoyed a prestigious space of its own. This was the auditorium in the Pirelli Tower, after it abandoned the premises of the “Ritrovo” in the old Brusada factory which escaped the bombings of 1943. This marked the beginning of a new chapter of cultural activities, with concerts, lectures, readings, screenings and presentations with prominent guests, including political and academic personalities, as well as writers, poets, and journalists, such as Italo Calvino, Umberto Eco, Guido Lopez, Salvatore Quasimodo and Mario Soldati.

At the same time, one of the country’s most advanced cultural forums was taking shape within the pages of Pirelli. Rivista d’informazione e di tecnica. Published from 1948 to 1972, generally bi-monthly and available at newsstands, Pirelli magazine bridged the gap between scientific-technical and humanistic culture. Its articles looked at issues concerning industrial production, science and technology alongside reflections on art, architecture, sociology, economics, urbanism and literature. The magazine had a wide range of illustrious contributors: Giulio Carlo Argan, Dino Buzzati, Camilla Cederna, Gillo Dorfles, Arrigo Levi, Eugenio Montale, Fernanda Pivano, Franco Quadri, Alberto Ronchey, Elio Vittorini and dozens of others. Its striking visuals were enriched by splendid photographic essays by masters such as Arno Hammacher, Pepi Merisio, Ugo Mulas, Federico Patellani, Fulvio Roiter, Enzo Sellerio, and illustrations by artists including Renato Guttuso, Riccardo Manzi and Alessandro Mendini.

The legacy of Pirelli magazine is preserved in the volume Industrial Humanism. An Anthology of Thoughts, Words, Images and Innovations, edited by the Pirelli Foundation and published by Mondadori in 2019. All 131 issues, along with a photographic archive comprising 6,000 images—3,500 published and 2,500 unprinted—are now kept in our Historical Archive. The collection includes the very first issue, with an editorial by Alberto Pirelli, who explains the original and authentic purpose of the publication: “This industry uses an enormous variety of materials […] it relies on the most diverse array of machines and tools […] So many ways to contribute to the evolution of modern life […] But if, in this magazine, we may at times allow ourselves to rise a little higher, we shall do so in the belief that every contribution to the mechanised world needs to come about within the broader framework of life’s highest social and cultural values.“