“The City Within the City” and Leopoldo Pirelli’s Vision

The Bicocca Project, one of Milan’s most significant urban planning ventures at the close of the millennium, was championed by Leopoldo Pirelli, president of Pirelli from 1965 to 1996. It is now being commemorated in a special way one hundred years after its founding

Pirelli and Milan share a bond that cannot be broken. We explored it in our study “Pirelli, a City and a Vision”, tracing its many expressions: its origins in Via Ponte Seveso shaped its identity and its products, and even their names. The images of the city provided a stage for its visual communication. From the post-war years to the 1960s, Pirelli’s cultural production entered into dialogue with that of Milan itself. The company also created signs that left their mark on both space and history—not only through place names but also on the map of the city’s most iconic landmarks. Among these was the Pirelli Tower, inaugurated in 1960. Designed by Gio Ponti, it redefined modern architecture and transformed Milan’s skyline. Then came the Bicocca Project one of the largest redevelopments in an area of Milan, which placed the city at the centre of international debate on industrial transformation. It was conceived by Leopoldo Pirelli together with the City of Milan, the Province of Milan, and the Lombardy Region.

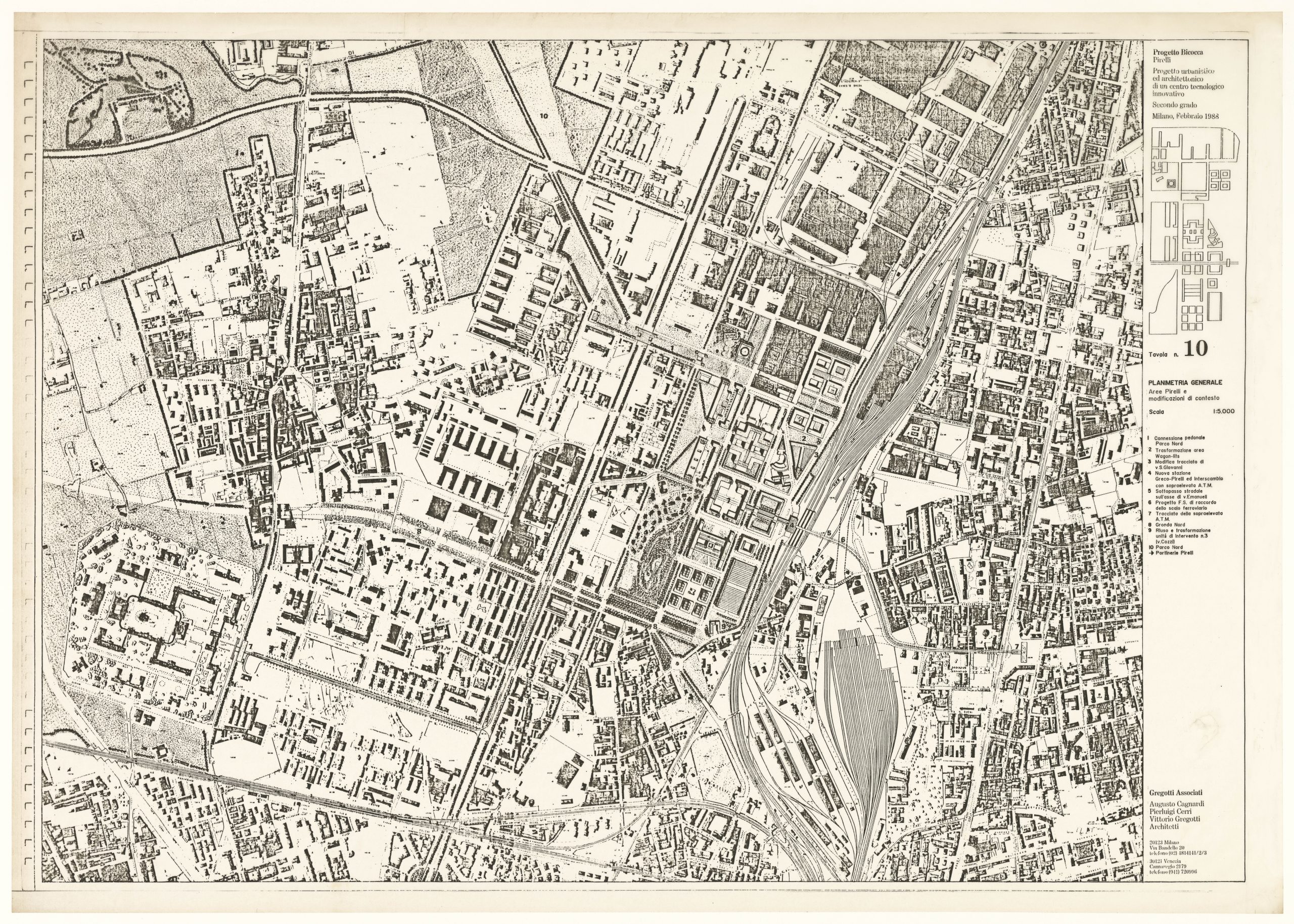

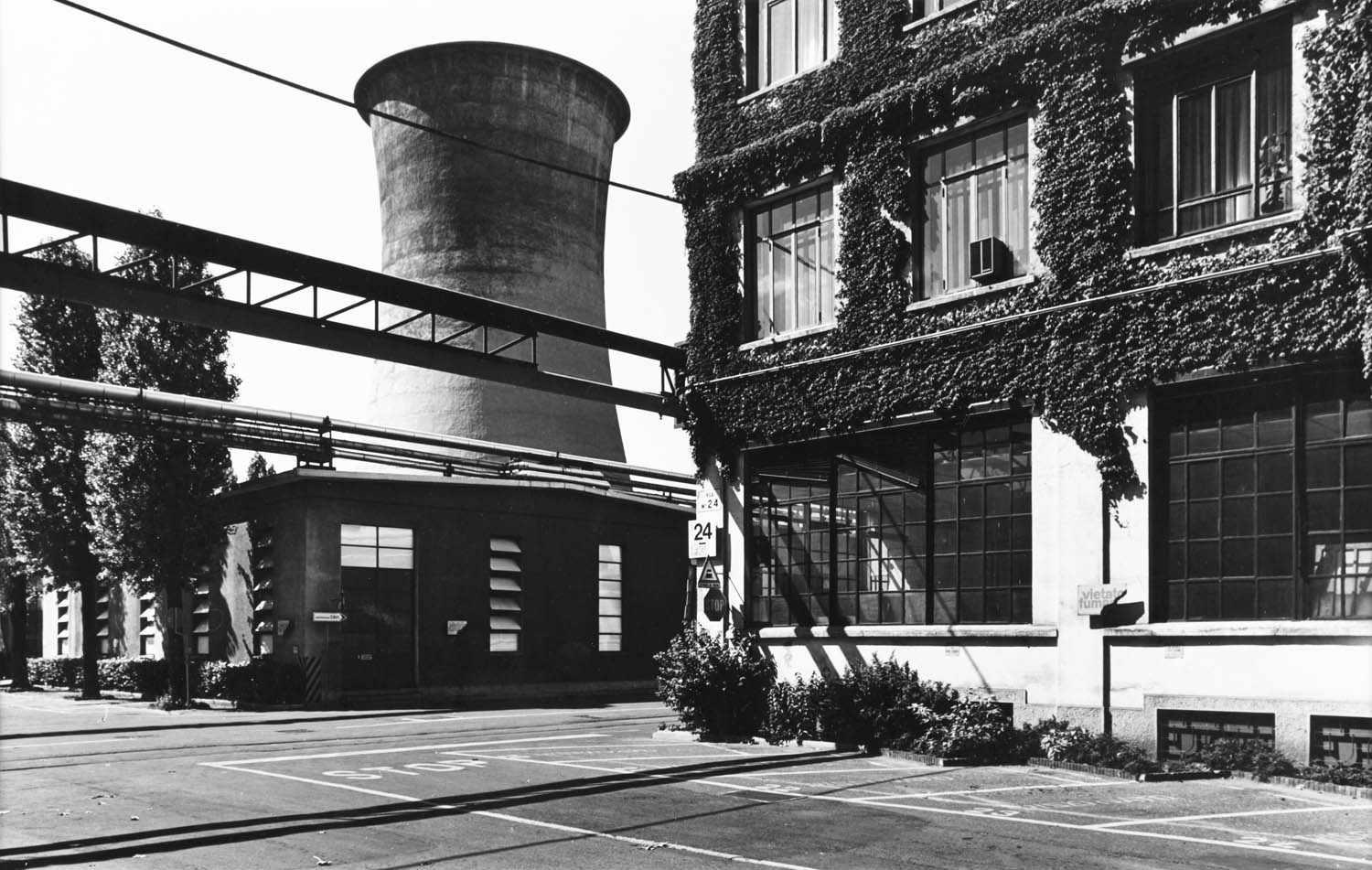

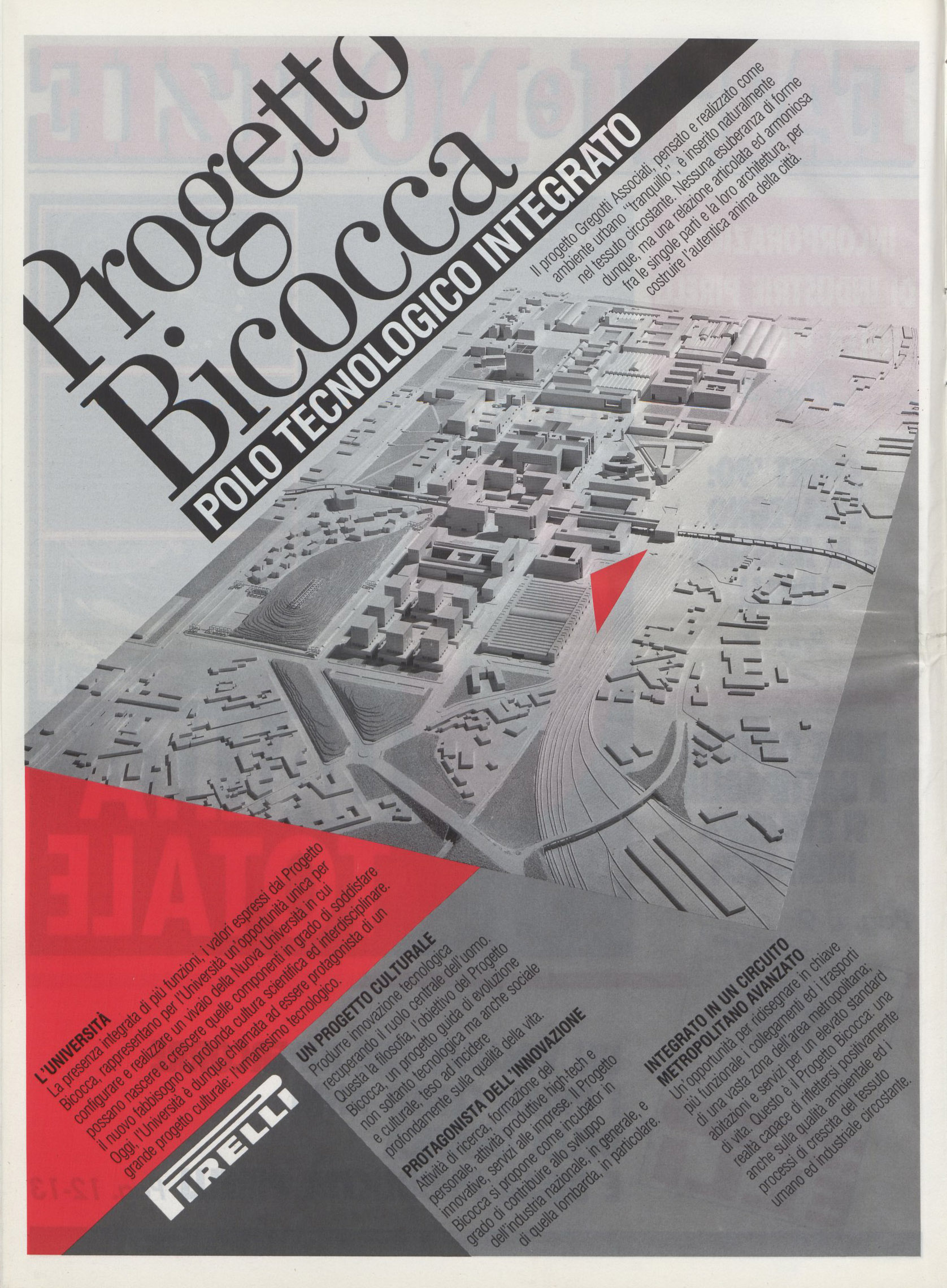

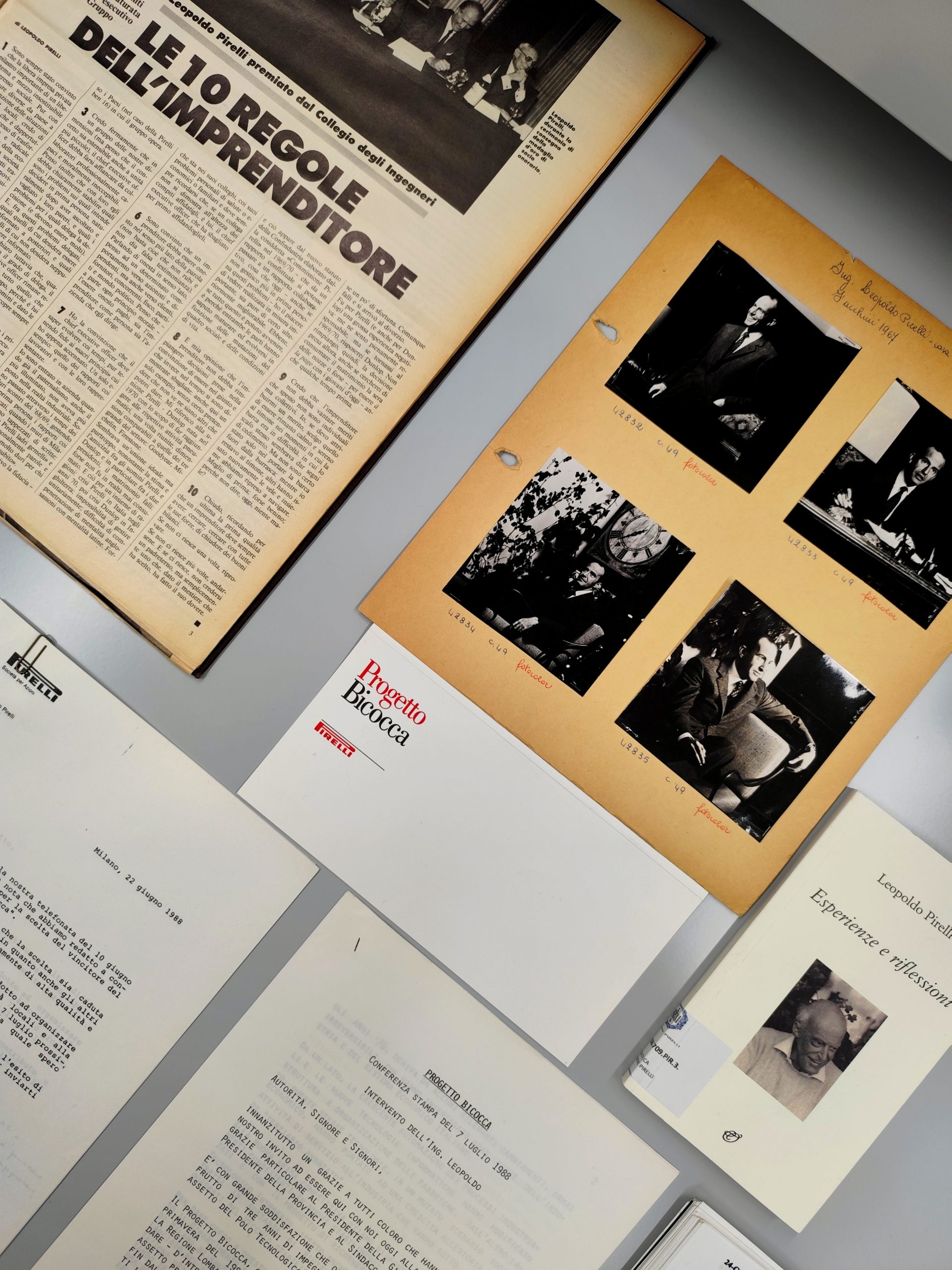

In 1985 the Bicocca plants were gradually decommissioned. This moment was captured in Gabriele Basilico’s photographs and in the director Silvio Soldini’s documentary La fabbrica sospesa, commissioned by Pirelli. That same year, the company launched an international competition by invitation for the transformation of its industrial areas, linking them to the city and creating an integrated, multifunctional technology hub. The letter sent to twenty of the world’s top architecture and urban planning firms bore the subject line: “Bicocca Project: Invitation to develop the theme of the future urban and architectural layout of an area located to the north of Milan, owned by Pirelli and known as Bicocca.”

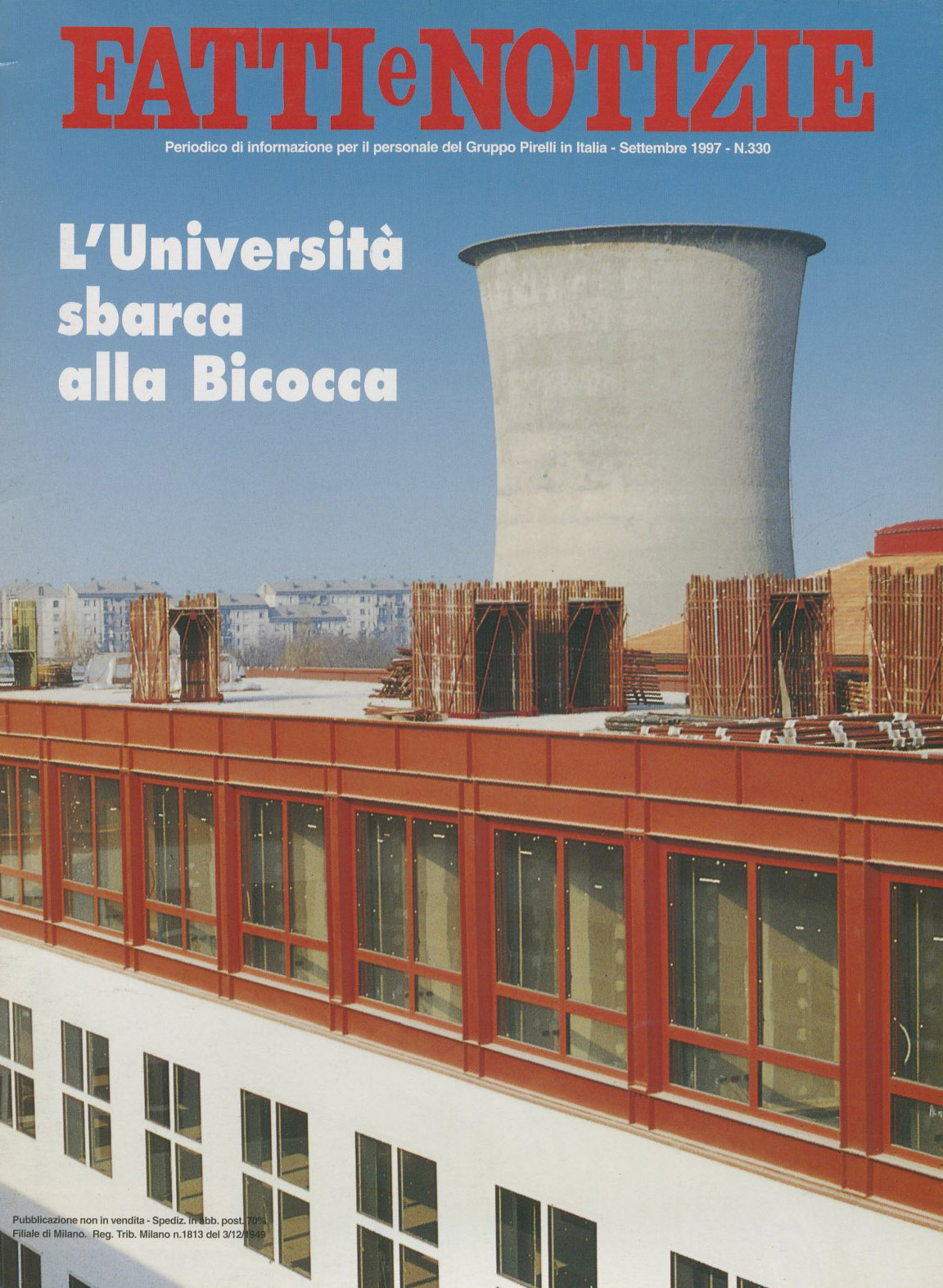

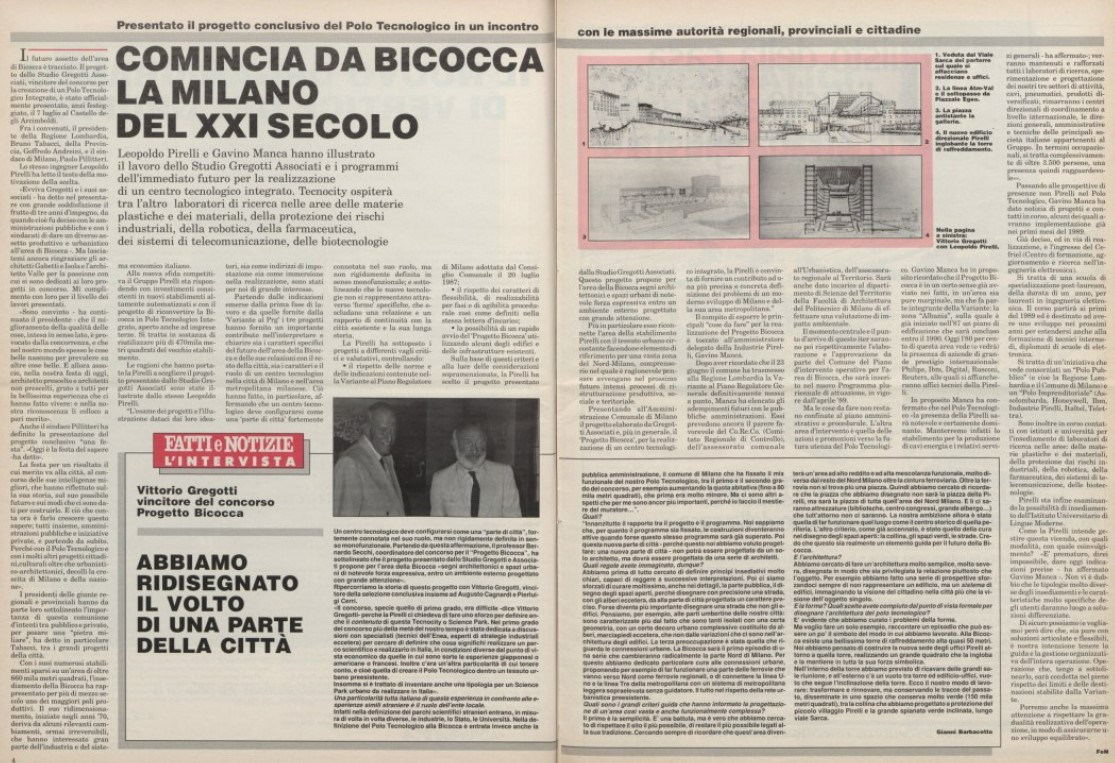

After a second round of judging, on 7 July 1988 Leopoldo Pirelli declared Gregotti Associati’s project to be the winner. “Comincia da Bicocca la Milano del XXI secolo” (“21st-Century Milan Begins in Bicocca”) was the title in Fatti e Notizie, the Pirelli Group’s Italian staff magazine. It reported on the presentation of the final phase to regional, provincial, and city authorities and published an interview with the architect Vittorio Gregotti.

The future of cities had long been a prime topic in Pirelli magazine during the 1950s and 1960s. Here, architects and town planners entered into a fascinating debate about the growth of urban settlements, as we explored in our article “Pirelli and the City of the Future“.

And “future” was the key word in the introduction that Leopoldo Pirelli wrote for Progetto Bicocca, published by Electa in 1986, which compiled all the submissions to the international competition for the “Integrated Technological Hub” on Pirelli’s Bicocca area. The publication is now preserved in the Pirelli Historical Archive, curated by the Pirelli Foundation. “We asked the designers who took part in the competition to redevelop a vast urban area, anticipating future needs that today we can at best guess at and catch sight of. We invited them to plan a city development based on new technologies, research, and an advanced services sector, while we entrepreneurs are still grappling with the problems of industrial society, large concentrations of workers (and, conversely, pockets of unemployment), as well as mass production. This is precisely why we turned to scholars of cities and urban cultures: for their ability to read into the future of humanity through the evolution of its habitat, from a perspective different from that of the economist, entrepreneur, or sociologist.”

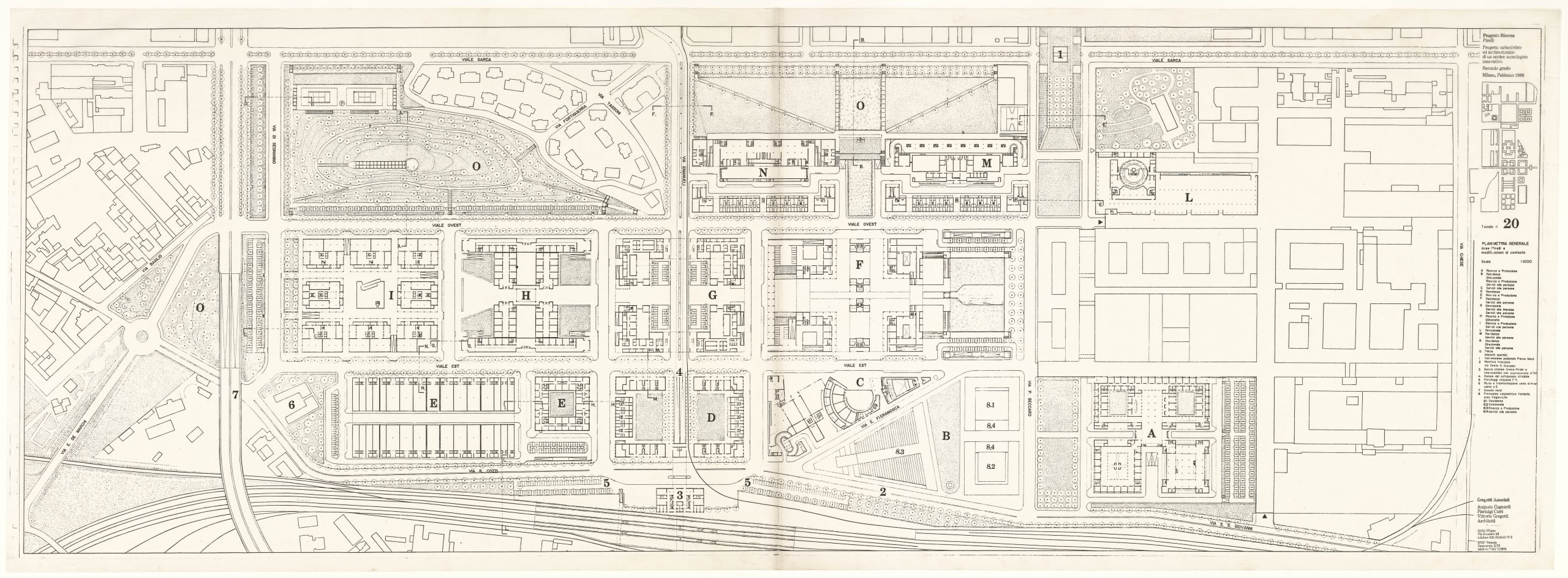

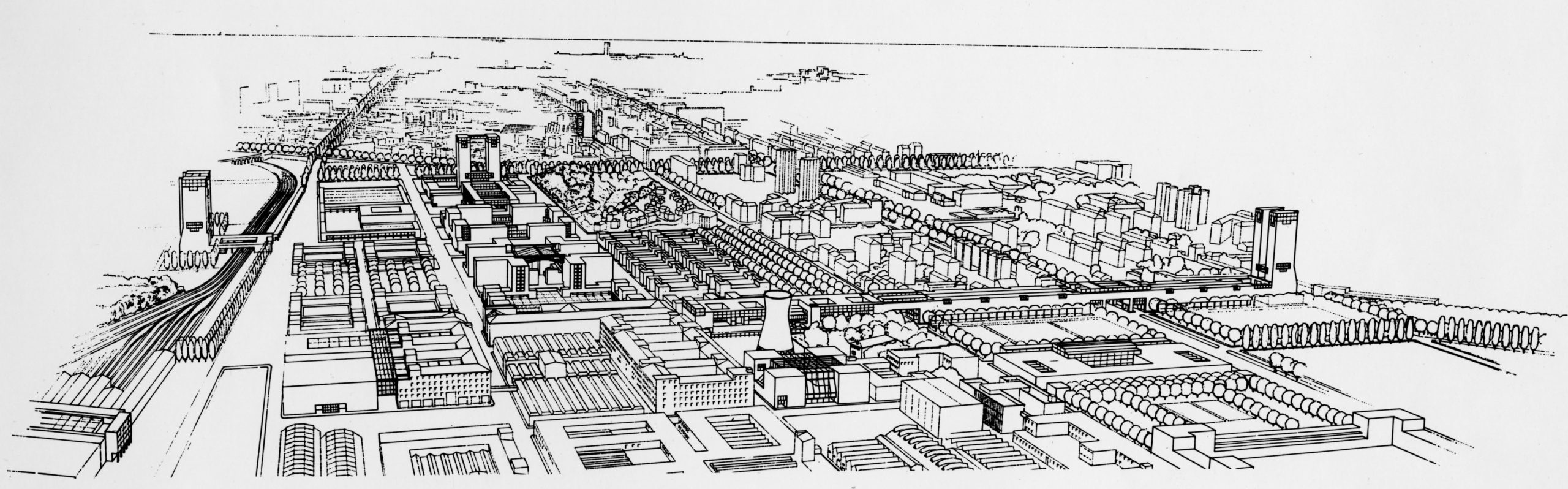

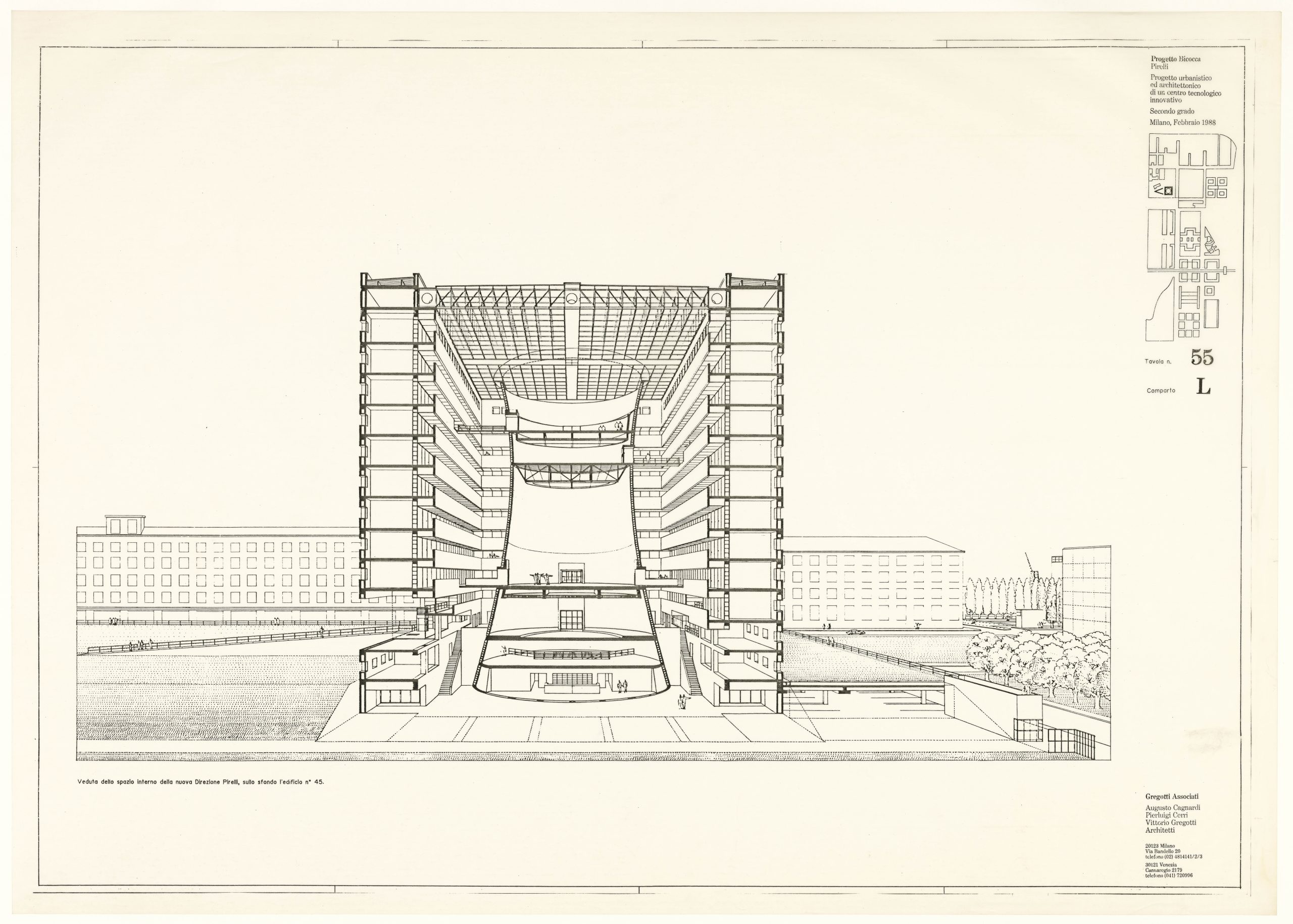

Gregotti Associati went on to design the master plan for the entire district and most of its buildings, combining the restoration of existing structures with new constructions: university facilities, public and private research centres, multinational headquarters, residential and office complexes, services, leisure spaces, and shopping areas, all interwoven with public green spaces and infrastructure. It also housed Pirelli’s headquarters, with its administration and research and development centre—its “head,” as Leopoldo Pirelli called it. This was taken up in the documentary Leopoldo Pirelli—Industrial Dedication and Civil Culture, produced by the Pirelli Foundation in 2017, ten years after his death.

From “product factories” to “factories of ideas and knowledge,” the Bicocca Project extends across 676,000 square metres, making it one of the largest urban renewal initiatives in Europe over the past thirty years. It introduced a new concept of modern urban planning and territorial regeneration.

It was a new take on the idea of a “city within a city,” as Leopoldo Pirelli described it. In presenting the invitation to the competition, he wrote: “I don’t think it can be considered rhetorical to say that this is a cultural and social contribution that Pirelli wishes to offer to the city of Milan, convinced, as it has always been, that economic progress cannot ignore these two fundamental aspects of civic life.”

The Bicocca Project, one of Milan’s most significant urban planning ventures at the close of the millennium, was championed by Leopoldo Pirelli, president of Pirelli from 1965 to 1996. It is now being commemorated in a special way one hundred years after its founding

Pirelli and Milan share a bond that cannot be broken. We explored it in our study “Pirelli, a City and a Vision”, tracing its many expressions: its origins in Via Ponte Seveso shaped its identity and its products, and even their names. The images of the city provided a stage for its visual communication. From the post-war years to the 1960s, Pirelli’s cultural production entered into dialogue with that of Milan itself. The company also created signs that left their mark on both space and history—not only through place names but also on the map of the city’s most iconic landmarks. Among these was the Pirelli Tower, inaugurated in 1960. Designed by Gio Ponti, it redefined modern architecture and transformed Milan’s skyline. Then came the Bicocca Project one of the largest redevelopments in an area of Milan, which placed the city at the centre of international debate on industrial transformation. It was conceived by Leopoldo Pirelli together with the City of Milan, the Province of Milan, and the Lombardy Region.

In 1985 the Bicocca plants were gradually decommissioned. This moment was captured in Gabriele Basilico’s photographs and in the director Silvio Soldini’s documentary La fabbrica sospesa, commissioned by Pirelli. That same year, the company launched an international competition by invitation for the transformation of its industrial areas, linking them to the city and creating an integrated, multifunctional technology hub. The letter sent to twenty of the world’s top architecture and urban planning firms bore the subject line: “Bicocca Project: Invitation to develop the theme of the future urban and architectural layout of an area located to the north of Milan, owned by Pirelli and known as Bicocca.”

After a second round of judging, on 7 July 1988 Leopoldo Pirelli declared Gregotti Associati’s project to be the winner. “Comincia da Bicocca la Milano del XXI secolo” (“21st-Century Milan Begins in Bicocca”) was the title in Fatti e Notizie, the Pirelli Group’s Italian staff magazine. It reported on the presentation of the final phase to regional, provincial, and city authorities and published an interview with the architect Vittorio Gregotti.

The future of cities had long been a prime topic in Pirelli magazine during the 1950s and 1960s. Here, architects and town planners entered into a fascinating debate about the growth of urban settlements, as we explored in our article “Pirelli and the City of the Future“.

And “future” was the key word in the introduction that Leopoldo Pirelli wrote for Progetto Bicocca, published by Electa in 1986, which compiled all the submissions to the international competition for the “Integrated Technological Hub” on Pirelli’s Bicocca area. The publication is now preserved in the Pirelli Historical Archive, curated by the Pirelli Foundation. “We asked the designers who took part in the competition to redevelop a vast urban area, anticipating future needs that today we can at best guess at and catch sight of. We invited them to plan a city development based on new technologies, research, and an advanced services sector, while we entrepreneurs are still grappling with the problems of industrial society, large concentrations of workers (and, conversely, pockets of unemployment), as well as mass production. This is precisely why we turned to scholars of cities and urban cultures: for their ability to read into the future of humanity through the evolution of its habitat, from a perspective different from that of the economist, entrepreneur, or sociologist.”

Gregotti Associati went on to design the master plan for the entire district and most of its buildings, combining the restoration of existing structures with new constructions: university facilities, public and private research centres, multinational headquarters, residential and office complexes, services, leisure spaces, and shopping areas, all interwoven with public green spaces and infrastructure. It also housed Pirelli’s headquarters, with its administration and research and development centre—its “head,” as Leopoldo Pirelli called it. This was taken up in the documentary Leopoldo Pirelli—Industrial Dedication and Civil Culture, produced by the Pirelli Foundation in 2017, ten years after his death.

From “product factories” to “factories of ideas and knowledge,” the Bicocca Project extends across 676,000 square metres, making it one of the largest urban renewal initiatives in Europe over the past thirty years. It introduced a new concept of modern urban planning and territorial regeneration.

It was a new take on the idea of a “city within a city,” as Leopoldo Pirelli described it. In presenting the invitation to the competition, he wrote: “I don’t think it can be considered rhetorical to say that this is a cultural and social contribution that Pirelli wishes to offer to the city of Milan, convinced, as it has always been, that economic progress cannot ignore these two fundamental aspects of civic life.”