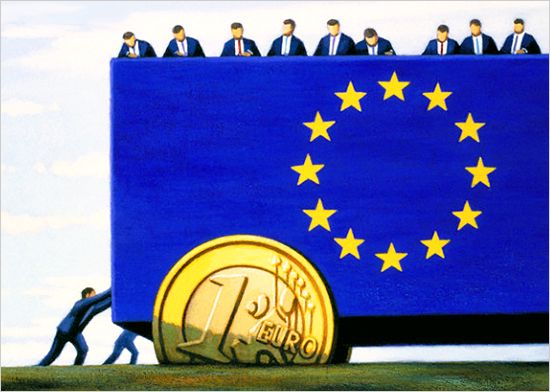

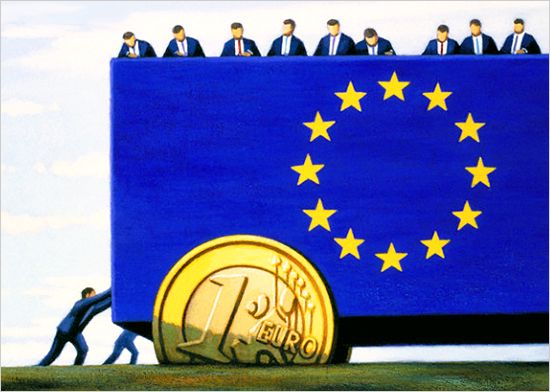

Businesses need a more integrated and efficient EU, with big investments in high-tech infrastructure, research and work

Italian companies thrive in the European Union and grow thanks to its open and competitive markets. Among the majority of entrepreneurs, there is still a clear conviction that there would be no growth without the EU. This is according to a survey from the Community Group, an economic communications company, which was published in Il Sole 24 Ore (10 May). The survey showed that 56.6% of entrepreneurs are firmly pro-EU, a higher percentage than for the general population, at 50.4%. In short, after the disaster of Brexit, the threat of a possible Italexit does not offer a convincing outlook for industry and jobs. That said, there is no shortage of concern and criticism about how the EU has worked so far, at least in the widespread perception in the economic world.

Naturally, 56.6% in favour of the EU is not an exciting percentage, either compared to a similar survey three years ago (in which 69% of entrepreneurs and 67% of the general public were pro-EU) or in light of opinions in the other major EU countries.

Severely affected by the financial crisis, fragile both socially and economically, with slower growth in terms of GDP, productivity and employment, Italy has once again been revealed as the weak link in an EU in difficulty. Held back for a long time by the inability of their leaders to carry out essential modernisation and social equity reforms with courage, broad sections of Italy’s population gave into temptation and listened to the political currents of sovereignty and populism, which find an easy scapegoat in the EU and the ‘powers’ of Brussels.

The Community Group survey covers the whole range of companies: large and medium-large, open, competitive and international, small and very small, those in difficulty because they are tied to a weak internal market, those that have innovated and successfully used EU Horizon 2020 digital economy funding, and others that have relied instead on contributions and funds from the shrinking public purse. While the first types are essential in terms of GDP growth due to exports, these others, of which there are many, especially in southern Italy and less dynamic economic areas, carry a strong electoral weight.

A different set of data gives a clearer picture. Thirty one per cent of entrepreneurs say that the euro has only created complications (compared to 26% three years ago), but 50.4% believe that the euro is still necessary despite the difficulties and 62% are convinced that things would be worse if the lira was reintroduced. So, one might conclude, the EU and the euro are here to stay despite everything.

But how to transform the euro into a real opportunity? 78.6% believe that greater coordination between regional economic policies is essential. This raises an essential point: new EU policies on taxation, economic development, research, education and welfare must be combined with monetary policies and common banking rules. So, more EU not less, and let’s bear in mind that all choices related to these issues are either made at a national level or entrusted to difficult negotiations at the European Council, where national governments are represented.

Moving on from opinions expressed in the polls to those of the leaders of business associations, views are clearer. Carlo Bonomi, the president of Assolombarda, asserts that ‘the return of sovereignty is not a mistake. It’s a crime.’ In the introduction to the book The Future of Europe, edited by the association, in collaboration with all the deans of Milan’s universities, he adds, ‘Europe is not an obstacle, but the best representative for our ideas on the world stage, because it carries more weight than anyone playing the game alone could.’ The explanation is clear: ‘The eleven Italian regions that today have interdependence rates with cross-border chains worth over 20% of their manufacturing – of which Lombardy, the Veneto and Emilia-Romagna obviously hold the top positions – account for 80% of Italian industrial added value by themselves. The data also shows that our small and medium international companies have been doing better than their French and German counterparts in recent years.’ The EU is an opportunity for growth, a trigger for development.

It is therefore necessary to think of ways in which the EU can work better, how to make more effective use of EU funds and how we can stimulate greater integration. The very opposite of the much-touted nationalism.

There is a lot of discussion about the need for a new Marshall Plan or Delors plan for big infrastructure, both material (the Turin-Lyon high-speed railway, for example) and intangible, to truly unify EU markets and communities. This would give infrastructure a symbolic and functional responsibility in strengthening EU relations (something we have spoken about several times in this blog). It’s essential to go beyond the fiscal compact, necessary as it is, and persist with the real economy, and the public and private EU investments needed for the environment, communications and research, to create a ‘smart land’ that strengthens integration, to improve quality of life and jobs. Companies are ready to play their part when it comes to investments, with ever greater commitment. There is widespread awareness that the economic challenge posed by the USA and China, should be played using the most sophisticated and innovative quality services, which offer greater value.

Infrastructure is another of the great challenges of relaunching the EU. It is to be financed in part by issuing Eurobonds and entrusted to efficient and well-coordinated management between structures in Brussels and EU and national agencies, with spending choices that avoid funds being lost or misused. This would be a real, far-sighted, productive development strategy, not a hand-out. Plans not just for strengthening the current Juncker plan but redefining the Investment Plan for Europe are being discussed in Brussels and the major EU capitals (starting with Berlin and Paris). These look beyond the European Parliament elections and identify ideas and proposals in the complicated international competitive framework.

Against this backdrop, Italy cannot afford to be isolated or marginal. For the Italian companies that continue to look from European players to the rest of the world with growing activism, there are strong nationalist and protectionist sentiments, looming demands for public influence in the direct management of the economy, a lack of respect for the autonomy of social bodies and the independence of major inspection authorities. The best Italian economy is still strongly characterized by liberal, reformist market companies, rooted in the productive areas of Italy and well equipped for international competition. A strengthened and, metaphorically speaking, reborn EU is good business indeed.

Italian companies thrive in the European Union and grow thanks to its open and competitive markets. Among the majority of entrepreneurs, there is still a clear conviction that there would be no growth without the EU. This is according to a survey from the Community Group, an economic communications company, which was published in Il Sole 24 Ore (10 May). The survey showed that 56.6% of entrepreneurs are firmly pro-EU, a higher percentage than for the general population, at 50.4%. In short, after the disaster of Brexit, the threat of a possible Italexit does not offer a convincing outlook for industry and jobs. That said, there is no shortage of concern and criticism about how the EU has worked so far, at least in the widespread perception in the economic world.

Naturally, 56.6% in favour of the EU is not an exciting percentage, either compared to a similar survey three years ago (in which 69% of entrepreneurs and 67% of the general public were pro-EU) or in light of opinions in the other major EU countries.

Severely affected by the financial crisis, fragile both socially and economically, with slower growth in terms of GDP, productivity and employment, Italy has once again been revealed as the weak link in an EU in difficulty. Held back for a long time by the inability of their leaders to carry out essential modernisation and social equity reforms with courage, broad sections of Italy’s population gave into temptation and listened to the political currents of sovereignty and populism, which find an easy scapegoat in the EU and the ‘powers’ of Brussels.

The Community Group survey covers the whole range of companies: large and medium-large, open, competitive and international, small and very small, those in difficulty because they are tied to a weak internal market, those that have innovated and successfully used EU Horizon 2020 digital economy funding, and others that have relied instead on contributions and funds from the shrinking public purse. While the first types are essential in terms of GDP growth due to exports, these others, of which there are many, especially in southern Italy and less dynamic economic areas, carry a strong electoral weight.

A different set of data gives a clearer picture. Thirty one per cent of entrepreneurs say that the euro has only created complications (compared to 26% three years ago), but 50.4% believe that the euro is still necessary despite the difficulties and 62% are convinced that things would be worse if the lira was reintroduced. So, one might conclude, the EU and the euro are here to stay despite everything.

But how to transform the euro into a real opportunity? 78.6% believe that greater coordination between regional economic policies is essential. This raises an essential point: new EU policies on taxation, economic development, research, education and welfare must be combined with monetary policies and common banking rules. So, more EU not less, and let’s bear in mind that all choices related to these issues are either made at a national level or entrusted to difficult negotiations at the European Council, where national governments are represented.

Moving on from opinions expressed in the polls to those of the leaders of business associations, views are clearer. Carlo Bonomi, the president of Assolombarda, asserts that ‘the return of sovereignty is not a mistake. It’s a crime.’ In the introduction to the book The Future of Europe, edited by the association, in collaboration with all the deans of Milan’s universities, he adds, ‘Europe is not an obstacle, but the best representative for our ideas on the world stage, because it carries more weight than anyone playing the game alone could.’ The explanation is clear: ‘The eleven Italian regions that today have interdependence rates with cross-border chains worth over 20% of their manufacturing – of which Lombardy, the Veneto and Emilia-Romagna obviously hold the top positions – account for 80% of Italian industrial added value by themselves. The data also shows that our small and medium international companies have been doing better than their French and German counterparts in recent years.’ The EU is an opportunity for growth, a trigger for development.

It is therefore necessary to think of ways in which the EU can work better, how to make more effective use of EU funds and how we can stimulate greater integration. The very opposite of the much-touted nationalism.

There is a lot of discussion about the need for a new Marshall Plan or Delors plan for big infrastructure, both material (the Turin-Lyon high-speed railway, for example) and intangible, to truly unify EU markets and communities. This would give infrastructure a symbolic and functional responsibility in strengthening EU relations (something we have spoken about several times in this blog). It’s essential to go beyond the fiscal compact, necessary as it is, and persist with the real economy, and the public and private EU investments needed for the environment, communications and research, to create a ‘smart land’ that strengthens integration, to improve quality of life and jobs. Companies are ready to play their part when it comes to investments, with ever greater commitment. There is widespread awareness that the economic challenge posed by the USA and China, should be played using the most sophisticated and innovative quality services, which offer greater value.

Infrastructure is another of the great challenges of relaunching the EU. It is to be financed in part by issuing Eurobonds and entrusted to efficient and well-coordinated management between structures in Brussels and EU and national agencies, with spending choices that avoid funds being lost or misused. This would be a real, far-sighted, productive development strategy, not a hand-out. Plans not just for strengthening the current Juncker plan but redefining the Investment Plan for Europe are being discussed in Brussels and the major EU capitals (starting with Berlin and Paris). These look beyond the European Parliament elections and identify ideas and proposals in the complicated international competitive framework.

Against this backdrop, Italy cannot afford to be isolated or marginal. For the Italian companies that continue to look from European players to the rest of the world with growing activism, there are strong nationalist and protectionist sentiments, looming demands for public influence in the direct management of the economy, a lack of respect for the autonomy of social bodies and the independence of major inspection authorities. The best Italian economy is still strongly characterized by liberal, reformist market companies, rooted in the productive areas of Italy and well equipped for international competition. A strengthened and, metaphorically speaking, reborn EU is good business indeed.