“Culture is bread”, the enlightenment of books to reflect on social and civic development

“Bread and culture” was the slogan of one of Milan’s most popular mayors, Antonio Greppi, a socialist, which gave a strategic sense to the commitment to the rebirth of the city and of Italy after the disasters of war and fascism: the rapid reopening of the bombed-out Scala, the reopening of factories, the reconstruction of houses and public services, the new course of free information and publishing, a horizon of enterprise and work.

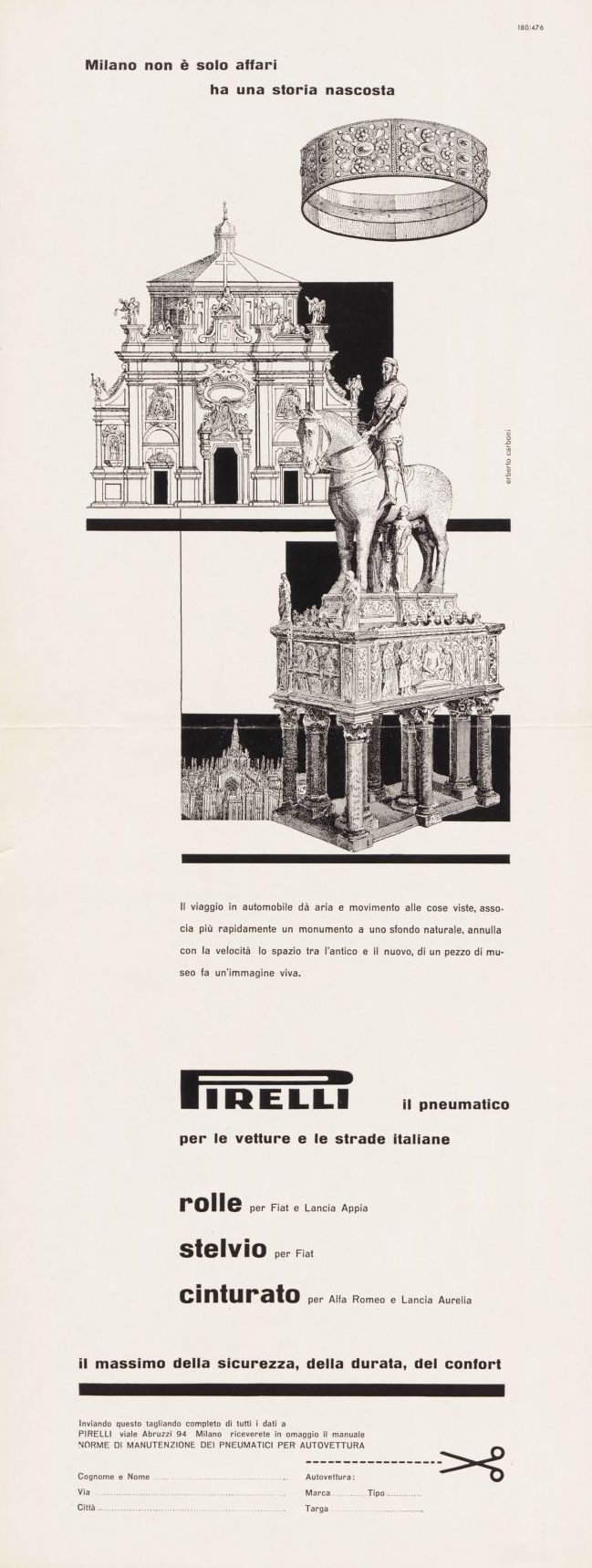

“Culture is bread” is the phrase that today stands at the entrance to the library of the Pirelli headquarters in Bicocca, to commemorate the commitment linked to the opening of the Pirelli Cultural Center in 1947, in those dynamic years full of hope. The Centre’s aim was to move beyond the horizon of ruins with activities of literature, theatre, music and photography. In this way, by supporting culture, the company defined itself not only as an economic player, but also as a civic and social player.

These two words, bread and culture, i.e. work and knowledge, well-being and learning, enterprise and development, come to mind when one considers the construction of the “Library of Light”, the large installation by the British artist Es Devlin in the Cortile d’onore of the Pinacoteca di Brera, with its 2,000 books on illuminated circular shelves in front of the statue of Maria Gaetana Agnesi, an 18th century mathematician and philosopher, the first woman to write a book on mathematics and the first to hold a university chair in the subject. The “Library of Light” is one of three installations (the others by Bob Wilson and Paolo Sorrentino) that will be on display during Design Week and the Salone del Mobile from 7 April. And here, too, business and culture, creativity and industrial production, the memory of “know-how” and innovation come together to form original syntheses, in the name of a true “polytechnic culture” that continues to combine humanistic and scientific knowledge, the sense of beauty and cutting-edge technologies. A very Italian perspective on the world that we can be proud of.

Bread and culture again today, in a contemporary dimension with historical awareness but looking to the future. Once again, the metropolis that exemplifies this perspective is Milan. Milan, city of books, stories, publications, cultured words, civilisation of dialogue between different tensions and opinions: “The power of ideas/the ideas of power” is the theme of BookCity Milano 2025. There are discussions on ongoing geopolitical and ethical crises, reflections on history and the future.

If we broaden our focus to the positive aspects that, despite everything, characterise our restless and troubled times, we find solid connotations of cultural practices and values in the Heritage Foundation’s Index of Economic Freedom 2025, which measures economic freedom in 184 countries each year. “A common thread links the degree of economic freedom and the well-being of citizens,” comments Alessandro De Nicola (La Repubblica/Affari & Finanza, 24 March), who is well aware of the strong links between the quality of life and work and economic freedom, cultural freedom and freedom of scientific research.

The Heritage Foundation is a conservative think tank, but it is widely respected for the rigor of its research. And in this Freedom Index, he emphasises that countries with “free” or “mostly free” economies have both higher standards of living and a significantly better quality of life than is usual in “repressed” economies. There is a clear relationship between economic freedom, political freedom and the rule of law. And therefore also between cultural freedoms and social and civil progress.

A clear conclusion can be drawn from this: books and freedom go hand in hand, freedom of ideas and economic development have a very close correlation. Nevertheless, the economy of knowledge and beauty and the awareness of the values of art and beauty must be considered as assets for the competitiveness of our economy. We must insist with conviction on the links between cultural heritage and sustainable, ecological and social development. Between critical thinking and creativity and between civil conscience and cultural wealth. It is a perspective that goes against the current temptations of “presentism”, of a distracted gaze on the flow of words and (increasingly fake) images on social media to which we devote only a few seconds of attention. It is against the degradation of words and “public discourse”.

It is a strong thesis, also supported by the words of Francesco Profumo, former Minister of Education and former president of the Compagnia di San Paolo: “In a world where artificial intelligence writes articles, diagnoses diseases and drives cars, critical thinking will be the only antidote to passive use of technology. If science gives us the tools to understand the world, art helps us imagine a new one.” And when it comes to “Steam” (the acronym for science, technology, engineering and mathematics, with the addition of the “a” for art), “it means recognising that innovation is born when science and creativity meet” (La Stampa, 30 March).

And so we return to the idea of the processes of knowledge and therefore to books and their being the “bread” of civilisation.

Our Constitution is a testament to this, and these ideas are clearly at the forefront. “Living words,” says Marta Cartabia, a constitutionalist of great rigour, vice-rector for social commitment and institutional affairs at Bocconi University in Milan (Corriere della Sera, 24 March). What are these living words? “Democracy and inviolable rights, human dignity, solidarity, equality, freedom, participation, work, development, health, the environment, future generations…”, says Cartabia. To which the provisions of the Constitution are linked, a barrier and a stimulus for all legislation. A reading of the values of our society, but also a strategy for the future. Freedoms proclaimed, but to be put into practice with consistency and perseverance.

Indeed, Marta Cartabia stresses: “Equality and solidarity, human dignity and freedom, and all the other great words of the Constitution must be lived, exercised, put into practice, discovered and rediscovered and, above all, practised every day, or risk being reduced to sterile rhetoric.”

This path also brings us back to social and civil values, Italian and European. Lest we forget what characterises Europe in its historical dimension and current state: the ability to combine civil rights and responsibilities, liberal democracy and democratic capitalism, incentives for individual enterprise and social and community values, economic growth and widespread prosperity. This is what makes us Europeans proud of what we have done in peace, after long and controversial periods of war and conflict and what makes us hateful in the eyes of those who are hostile to us.

A useful book on this subject is “Moniti all’Europa” (Warnings to Europe) by Thomas Mann, political and civil essays written between 1922 and 1945 (a new edition was published by Mondadori in 2017, with a foreword by the President Emeritus of the Republic, Giorgio Napolitano”). It points to a common destiny after the Nazi tragedy. The commitment to assert the power of reason and dialogue. And, in this essential reading, the relationship between democracy and culture.

(photo Getty Images)

“Bread and culture” was the slogan of one of Milan’s most popular mayors, Antonio Greppi, a socialist, which gave a strategic sense to the commitment to the rebirth of the city and of Italy after the disasters of war and fascism: the rapid reopening of the bombed-out Scala, the reopening of factories, the reconstruction of houses and public services, the new course of free information and publishing, a horizon of enterprise and work.

“Culture is bread” is the phrase that today stands at the entrance to the library of the Pirelli headquarters in Bicocca, to commemorate the commitment linked to the opening of the Pirelli Cultural Center in 1947, in those dynamic years full of hope. The Centre’s aim was to move beyond the horizon of ruins with activities of literature, theatre, music and photography. In this way, by supporting culture, the company defined itself not only as an economic player, but also as a civic and social player.

These two words, bread and culture, i.e. work and knowledge, well-being and learning, enterprise and development, come to mind when one considers the construction of the “Library of Light”, the large installation by the British artist Es Devlin in the Cortile d’onore of the Pinacoteca di Brera, with its 2,000 books on illuminated circular shelves in front of the statue of Maria Gaetana Agnesi, an 18th century mathematician and philosopher, the first woman to write a book on mathematics and the first to hold a university chair in the subject. The “Library of Light” is one of three installations (the others by Bob Wilson and Paolo Sorrentino) that will be on display during Design Week and the Salone del Mobile from 7 April. And here, too, business and culture, creativity and industrial production, the memory of “know-how” and innovation come together to form original syntheses, in the name of a true “polytechnic culture” that continues to combine humanistic and scientific knowledge, the sense of beauty and cutting-edge technologies. A very Italian perspective on the world that we can be proud of.

Bread and culture again today, in a contemporary dimension with historical awareness but looking to the future. Once again, the metropolis that exemplifies this perspective is Milan. Milan, city of books, stories, publications, cultured words, civilisation of dialogue between different tensions and opinions: “The power of ideas/the ideas of power” is the theme of BookCity Milano 2025. There are discussions on ongoing geopolitical and ethical crises, reflections on history and the future.

If we broaden our focus to the positive aspects that, despite everything, characterise our restless and troubled times, we find solid connotations of cultural practices and values in the Heritage Foundation’s Index of Economic Freedom 2025, which measures economic freedom in 184 countries each year. “A common thread links the degree of economic freedom and the well-being of citizens,” comments Alessandro De Nicola (La Repubblica/Affari & Finanza, 24 March), who is well aware of the strong links between the quality of life and work and economic freedom, cultural freedom and freedom of scientific research.

The Heritage Foundation is a conservative think tank, but it is widely respected for the rigor of its research. And in this Freedom Index, he emphasises that countries with “free” or “mostly free” economies have both higher standards of living and a significantly better quality of life than is usual in “repressed” economies. There is a clear relationship between economic freedom, political freedom and the rule of law. And therefore also between cultural freedoms and social and civil progress.

A clear conclusion can be drawn from this: books and freedom go hand in hand, freedom of ideas and economic development have a very close correlation. Nevertheless, the economy of knowledge and beauty and the awareness of the values of art and beauty must be considered as assets for the competitiveness of our economy. We must insist with conviction on the links between cultural heritage and sustainable, ecological and social development. Between critical thinking and creativity and between civil conscience and cultural wealth. It is a perspective that goes against the current temptations of “presentism”, of a distracted gaze on the flow of words and (increasingly fake) images on social media to which we devote only a few seconds of attention. It is against the degradation of words and “public discourse”.

It is a strong thesis, also supported by the words of Francesco Profumo, former Minister of Education and former president of the Compagnia di San Paolo: “In a world where artificial intelligence writes articles, diagnoses diseases and drives cars, critical thinking will be the only antidote to passive use of technology. If science gives us the tools to understand the world, art helps us imagine a new one.” And when it comes to “Steam” (the acronym for science, technology, engineering and mathematics, with the addition of the “a” for art), “it means recognising that innovation is born when science and creativity meet” (La Stampa, 30 March).

And so we return to the idea of the processes of knowledge and therefore to books and their being the “bread” of civilisation.

Our Constitution is a testament to this, and these ideas are clearly at the forefront. “Living words,” says Marta Cartabia, a constitutionalist of great rigour, vice-rector for social commitment and institutional affairs at Bocconi University in Milan (Corriere della Sera, 24 March). What are these living words? “Democracy and inviolable rights, human dignity, solidarity, equality, freedom, participation, work, development, health, the environment, future generations…”, says Cartabia. To which the provisions of the Constitution are linked, a barrier and a stimulus for all legislation. A reading of the values of our society, but also a strategy for the future. Freedoms proclaimed, but to be put into practice with consistency and perseverance.

Indeed, Marta Cartabia stresses: “Equality and solidarity, human dignity and freedom, and all the other great words of the Constitution must be lived, exercised, put into practice, discovered and rediscovered and, above all, practised every day, or risk being reduced to sterile rhetoric.”

This path also brings us back to social and civil values, Italian and European. Lest we forget what characterises Europe in its historical dimension and current state: the ability to combine civil rights and responsibilities, liberal democracy and democratic capitalism, incentives for individual enterprise and social and community values, economic growth and widespread prosperity. This is what makes us Europeans proud of what we have done in peace, after long and controversial periods of war and conflict and what makes us hateful in the eyes of those who are hostile to us.

A useful book on this subject is “Moniti all’Europa” (Warnings to Europe) by Thomas Mann, political and civil essays written between 1922 and 1945 (a new edition was published by Mondadori in 2017, with a foreword by the President Emeritus of the Republic, Giorgio Napolitano”). It points to a common destiny after the Nazi tragedy. The commitment to assert the power of reason and dialogue. And, in this essential reading, the relationship between democracy and culture.

(photo Getty Images)