“How is the night?

Clear.”

These are the last lines in Bertolt Brecht‘s Vita di Galileo (Life of Galileo): the scientist has just given in, has bowed to the power of the doctors of the Church, and has disavowed his discovery that the Sun is at the centre of the universe and Earth is a planet revolving around it, thus tarnishing the integrity of scientific evidence in favour of the theologians’ beliefs. He has surrendered, out of fear, to those powerful authorities. Yet, he doesn’t give up and continues to study the stars, the laws of physics and astronomy, because science always entails a certain amount of strength, and research, discoveries, knowledge and truth, – to be verified, debated, put to the test – embody extraordinary beauty.

A new beginning we must experience.

A night sky we must contemplate.

“How is the night?

Clear.”

In spite of everything.

Vita di Galileo premiered at the Piccolo Teatro di Milano on 22 April 1963. The director was Giorgio Strelher and the starring role was entrusted to Tino Buazzelli, who gave one of the most intense and effective performances known in the history of theatre. Even today, people still reminisce about Strelher’s play, especially as part of the Piccolo Teatro’s initiatives to commemorate Strelher’s 100th birthday, because those dialogues, those scenes, that performance – intense and piercing, yet full of hope – captured the poignant moment when human experience has to deal with scientific and moral issues that will make the history of progress and development, leading to a more balanced civilisation.

Thus, the night is clear – even in our difficult times, marked by health crises and technological frailty, extraordinary opportunities for economic growth and insufferable social disparities, great scientific progress and increasing environmental disruption, heart-rending wars, such as the one in Ukraine, and the violation of millions of people’s right to a better future.

These are uncertain times, as we’re coming to terms with the dangers of a recession, of growing inflation, with rising rates leading – after years of stillness – to higher prices, and with rifts in the international trade system. Jamie Dimon, CEO of major international bank JP Morgan, expressed his concerns and his prediction that “an economic storm is approaching” now needs to be taken seriously.

Risky times, then, which we might be tempted to view poetically, as per Eugenio Montale’s words: “All we can tell you today/ is what we are not/ what we want not”), though we should also confide in the opportunities – related to health, quality of life, improvement of working conditions – brought on by scientific achievement. We need to move forward, through the crisis, avoiding the shadowy traps of so-called “magical thinking” that fears knowledge and science, and welcoming the prospects that research offers in terms of tackling the challenges engendered by such a complex period (as the work of Giorgio Parisi, winner of the 2021 Nobel Prize in Physics, shows). In his Lezioni americane (American Lessons), Italo Calvino detects that same complexity as a constant feature of the human condition, as well as a drive towards innovation, following non-linear paths and thinking patterns, yet with the awareness that, in spite of everything – twists, disagreements and contradictions – as we journey through this night we can already glimpse the first light of dawn, just like Galileo.

Particular sites exist where these complex and contentious cultural and social conditions interweave and evolve: production facilities, industrial plants, factories. Factories, indeed: an outdated word that has, nonetheless, recently made a comeback and is now at the heart of public debate, in a period where Italian and European “industrial pride” is on the rise.

In the 19th century, factories were a symbol of modernity, of the new dimensions of production and consumption, of disruptive social and economic transformation. Then, over a long and controversial 20th century, a century marked by the advent of cars and mass mobility, chemistry and telecommunications, consumption and new lifestyles, conflicts and widespread wealth, factories became central to the political and economic spheres, And even now, while scientific and technological innovations, the digital economy and Artificial Intelligence, are leading “services” and so-called “third-sector” activities to the forefront, factories – or, even better, neo-factories – maintain their pivotal position within the economy, because that’s where developments affecting science and technology, work and life, research and production, economic needs and social values, innovation and environmental protection, converge, generating competitiveness and environmental and social sustainability.

At the beginning of the new millennium, factories seemed to have disappeared, were confined to large yet peripheral areas, were hidden away from the heart of “progress” – now they’re back on the scene, with new assets and new values.

Factories, that is, “civilised machinery” and “industrial humanism” – now turning into “digital humanism” as it gradually incorporates scientific and technological innovations. Special places where original production and cultural concepts arise and are experimented with, and in which the awareness of a relationship between industry and culture, of the vital bond between industrial manufacturing and cultural production, is growing.

In fact, industry and culture don’t actually belong to two different spheres, but are part of the same world (this gave rise to a long debate last week, in Rome, at the Stati Generali del Patrimonio Industriale (General assembly on industrial heritage) conference, organised by AIPAI (Italian association for industrial archaeological heritage) and Museimpresa (Italian association of business archives and corporate museums).

Doing business, especially in terms of industrial manufacturing, means investing in – and working on – the changes that are reshaping markets, consumption, production technologies. It means focusing on research and innovation, keeping abreast of technical and social transformations. Innovation it’s key, as it embodies a strong cultural and symbolic significance and as it encompasses pretty much everything: technologies, materials, new products and the new processes required to make them, industrial relationships between the various segments of the corporate and working worlds, corporate governance, the languages of marketing and communication. What’s all this if not scientific culture, economic culture, humanist culture – in brief, entrepreneurial culture? In other words, we need to shift from the traditional juxtaposition of “business and culture” to a more robust, valuable notion: “business is culture”.

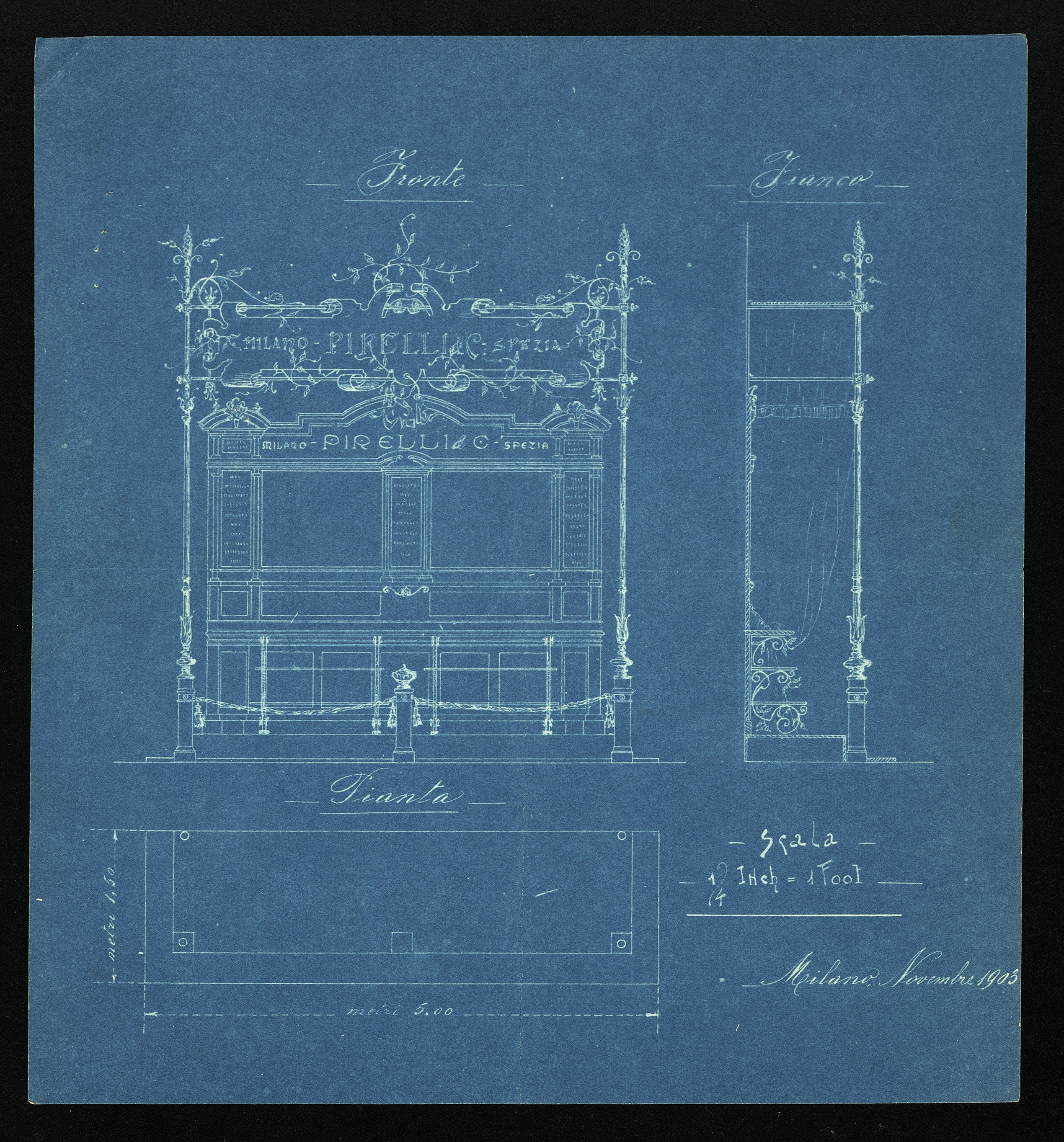

In this context, a historical perspective will pick up on a particular concept, that of a “progressive” company, to emphasise the term used by Giovanni Battista Pirelli in a speech from 1873, one year after the company was founded (and its echo resounds among the pages of Una storia al futuro. Pirelli, 150 anni di industria, innovazione, cultura (Thinking Ahead. Pirelli, 150 years of industry, innovation, culture), recently published by Marsilio).

A company, that is, bolstered by cutting-edge technologies applied to the manufacturing of rubber products, but also a company that shows great care for the “human touch”, and that is open to innovation in the widest sense of the term (products and production, materials, corporate organisation, social commitments). A company intensely aware of its role, amid agreements and disagreements, as a driving force in building a common history offering a better economic, cultural and social balance.

Wisdom, both old and new.

“All things are full of labour more than we can say; the eye is not satisfied with seeing, nor the ear filled with hearing” we read in Ecclesiastes 1.8 – essential reading when one has to deal with history and the pace of its change. And the idea that “the eye is not satisfied with seeing” extraordinarily captures a desire for discovery, scientific curiosity, technological passion – essentially, all that restlessness about innovation that characterises an enterprise – not much driven by profit (although that’s still a requisite) but, above all, by change, as a company’s culture and ethics will inform values, conditions and the future, as well as its own activities and attitudes.

Innovation, then.

“Adess ghe capissarem on quaicoss: andemm a guardagh denter” (Let’s try and understand it: let’s have a look inside) were the words beloved by Luigi Emanueli, engineer and father of modern electrical engineering, who, in the first half of the early 20th century, introduced several innovations related to Pirelli cables and tyres. Let’s, indeed, have a look inside machines and products, and fully understand how they work. Let’s build, disassemble and reassemble. Let’s glimpse inside with a scientific attitude and mechanical knowledge.

Those words also encapsulate a deeper feeling that has inspired the best developments and competitive aspects of the entire Italian industry. A commitment to do and do well, creative intelligence, a preoccupation with constant improvement – essentially, the acknowledgement of one’s own excellence, which allows Italy to remain as competitive – in technical and production terms – as other European and international countries that benefit from robust businesses, financial wealth, availability of raw materials, public funding for enterprises, scientific research and its related technological applications. The EU Recovery Fund, which in Italy takes the shape of PNRR (Italian recovery and resilience plan), points in this direction, just as other potential future EU plans related to energy and safety might do. The path is steep, but it’s the one we need to follow – finding strength, perhaps, in Galileo and in a “clear night” for science.

“How is the night?

Clear.”

These are the last lines in Bertolt Brecht‘s Vita di Galileo (Life of Galileo): the scientist has just given in, has bowed to the power of the doctors of the Church, and has disavowed his discovery that the Sun is at the centre of the universe and Earth is a planet revolving around it, thus tarnishing the integrity of scientific evidence in favour of the theologians’ beliefs. He has surrendered, out of fear, to those powerful authorities. Yet, he doesn’t give up and continues to study the stars, the laws of physics and astronomy, because science always entails a certain amount of strength, and research, discoveries, knowledge and truth, – to be verified, debated, put to the test – embody extraordinary beauty.

A new beginning we must experience.

A night sky we must contemplate.

“How is the night?

Clear.”

In spite of everything.

Vita di Galileo premiered at the Piccolo Teatro di Milano on 22 April 1963. The director was Giorgio Strelher and the starring role was entrusted to Tino Buazzelli, who gave one of the most intense and effective performances known in the history of theatre. Even today, people still reminisce about Strelher’s play, especially as part of the Piccolo Teatro’s initiatives to commemorate Strelher’s 100th birthday, because those dialogues, those scenes, that performance – intense and piercing, yet full of hope – captured the poignant moment when human experience has to deal with scientific and moral issues that will make the history of progress and development, leading to a more balanced civilisation.

Thus, the night is clear – even in our difficult times, marked by health crises and technological frailty, extraordinary opportunities for economic growth and insufferable social disparities, great scientific progress and increasing environmental disruption, heart-rending wars, such as the one in Ukraine, and the violation of millions of people’s right to a better future.

These are uncertain times, as we’re coming to terms with the dangers of a recession, of growing inflation, with rising rates leading – after years of stillness – to higher prices, and with rifts in the international trade system. Jamie Dimon, CEO of major international bank JP Morgan, expressed his concerns and his prediction that “an economic storm is approaching” now needs to be taken seriously.

Risky times, then, which we might be tempted to view poetically, as per Eugenio Montale’s words: “All we can tell you today/ is what we are not/ what we want not”), though we should also confide in the opportunities – related to health, quality of life, improvement of working conditions – brought on by scientific achievement. We need to move forward, through the crisis, avoiding the shadowy traps of so-called “magical thinking” that fears knowledge and science, and welcoming the prospects that research offers in terms of tackling the challenges engendered by such a complex period (as the work of Giorgio Parisi, winner of the 2021 Nobel Prize in Physics, shows). In his Lezioni americane (American Lessons), Italo Calvino detects that same complexity as a constant feature of the human condition, as well as a drive towards innovation, following non-linear paths and thinking patterns, yet with the awareness that, in spite of everything – twists, disagreements and contradictions – as we journey through this night we can already glimpse the first light of dawn, just like Galileo.

Particular sites exist where these complex and contentious cultural and social conditions interweave and evolve: production facilities, industrial plants, factories. Factories, indeed: an outdated word that has, nonetheless, recently made a comeback and is now at the heart of public debate, in a period where Italian and European “industrial pride” is on the rise.

In the 19th century, factories were a symbol of modernity, of the new dimensions of production and consumption, of disruptive social and economic transformation. Then, over a long and controversial 20th century, a century marked by the advent of cars and mass mobility, chemistry and telecommunications, consumption and new lifestyles, conflicts and widespread wealth, factories became central to the political and economic spheres, And even now, while scientific and technological innovations, the digital economy and Artificial Intelligence, are leading “services” and so-called “third-sector” activities to the forefront, factories – or, even better, neo-factories – maintain their pivotal position within the economy, because that’s where developments affecting science and technology, work and life, research and production, economic needs and social values, innovation and environmental protection, converge, generating competitiveness and environmental and social sustainability.

At the beginning of the new millennium, factories seemed to have disappeared, were confined to large yet peripheral areas, were hidden away from the heart of “progress” – now they’re back on the scene, with new assets and new values.

Factories, that is, “civilised machinery” and “industrial humanism” – now turning into “digital humanism” as it gradually incorporates scientific and technological innovations. Special places where original production and cultural concepts arise and are experimented with, and in which the awareness of a relationship between industry and culture, of the vital bond between industrial manufacturing and cultural production, is growing.

In fact, industry and culture don’t actually belong to two different spheres, but are part of the same world (this gave rise to a long debate last week, in Rome, at the Stati Generali del Patrimonio Industriale (General assembly on industrial heritage) conference, organised by AIPAI (Italian association for industrial archaeological heritage) and Museimpresa (Italian association of business archives and corporate museums).

Doing business, especially in terms of industrial manufacturing, means investing in – and working on – the changes that are reshaping markets, consumption, production technologies. It means focusing on research and innovation, keeping abreast of technical and social transformations. Innovation it’s key, as it embodies a strong cultural and symbolic significance and as it encompasses pretty much everything: technologies, materials, new products and the new processes required to make them, industrial relationships between the various segments of the corporate and working worlds, corporate governance, the languages of marketing and communication. What’s all this if not scientific culture, economic culture, humanist culture – in brief, entrepreneurial culture? In other words, we need to shift from the traditional juxtaposition of “business and culture” to a more robust, valuable notion: “business is culture”.

In this context, a historical perspective will pick up on a particular concept, that of a “progressive” company, to emphasise the term used by Giovanni Battista Pirelli in a speech from 1873, one year after the company was founded (and its echo resounds among the pages of Una storia al futuro. Pirelli, 150 anni di industria, innovazione, cultura (Thinking Ahead. Pirelli, 150 years of industry, innovation, culture), recently published by Marsilio).

A company, that is, bolstered by cutting-edge technologies applied to the manufacturing of rubber products, but also a company that shows great care for the “human touch”, and that is open to innovation in the widest sense of the term (products and production, materials, corporate organisation, social commitments). A company intensely aware of its role, amid agreements and disagreements, as a driving force in building a common history offering a better economic, cultural and social balance.

Wisdom, both old and new.

“All things are full of labour more than we can say; the eye is not satisfied with seeing, nor the ear filled with hearing” we read in Ecclesiastes 1.8 – essential reading when one has to deal with history and the pace of its change. And the idea that “the eye is not satisfied with seeing” extraordinarily captures a desire for discovery, scientific curiosity, technological passion – essentially, all that restlessness about innovation that characterises an enterprise – not much driven by profit (although that’s still a requisite) but, above all, by change, as a company’s culture and ethics will inform values, conditions and the future, as well as its own activities and attitudes.

Innovation, then.

“Adess ghe capissarem on quaicoss: andemm a guardagh denter” (Let’s try and understand it: let’s have a look inside) were the words beloved by Luigi Emanueli, engineer and father of modern electrical engineering, who, in the first half of the early 20th century, introduced several innovations related to Pirelli cables and tyres. Let’s, indeed, have a look inside machines and products, and fully understand how they work. Let’s build, disassemble and reassemble. Let’s glimpse inside with a scientific attitude and mechanical knowledge.

Those words also encapsulate a deeper feeling that has inspired the best developments and competitive aspects of the entire Italian industry. A commitment to do and do well, creative intelligence, a preoccupation with constant improvement – essentially, the acknowledgement of one’s own excellence, which allows Italy to remain as competitive – in technical and production terms – as other European and international countries that benefit from robust businesses, financial wealth, availability of raw materials, public funding for enterprises, scientific research and its related technological applications. The EU Recovery Fund, which in Italy takes the shape of PNRR (Italian recovery and resilience plan), points in this direction, just as other potential future EU plans related to energy and safety might do. The path is steep, but it’s the one we need to follow – finding strength, perhaps, in Galileo and in a “clear night” for science.