Read more...

Read more...

Pirelli opens libraries in Bicocca and Bollate

Two new company libraries were opened this morning in Milan Bicocca and at the Bollate plant at the presence of Pirelli Executive Vice President and CEO Marco Tronchetti Provera, Municipal Councillor for Culture Filippo Del Corno, Fondazione Pirelli Managing Director Antonio Calabrò and AIE President Federico Motta. Lella Costa, in her capacity as Honorary Member of Fondo Scuola Italia, also attended. The opening of the libraries at the Pirelli Headquarters is part of the promotional campaign #ioleggoperché 2016 (why I read) organised by AIE (the Italian Publishers Association) of which Pirelli is main partner and that this year focuses on the development of promotional activities and the creation of company and school libraries.

Approximately 3500 books (at the Milan Headquarters and the Bollate Plant) will be made available to employees for lending and reference: titles include the most recent best-sellers, novels, non-fiction, thrillers, science-fiction and much more. The opening of these libraries follows the tradition of Pirelli as promoter of activities aimed at fostering reading and the dissemination of culture at the work place, in the steps of the first library opened in 1928 and the Pirelli Cultural Centre established with the goal of “grouping and coordinating educational activities” that has organised musical events and plays, exhibitions, film festivals and conferences with world-famed writers and artists over the years. The libraries join the one successfully operating at the Pirelli Industrial Hub in Settimo Torinese.

Two new company libraries were opened this morning in Milan Bicocca and at the Bollate plant at the presence of Pirelli Executive Vice President and CEO Marco Tronchetti Provera, Municipal Councillor for Culture Filippo Del Corno, Fondazione Pirelli Managing Director Antonio Calabrò and AIE President Federico Motta. Lella Costa, in her capacity as Honorary Member of Fondo Scuola Italia, also attended. The opening of the libraries at the Pirelli Headquarters is part of the promotional campaign #ioleggoperché 2016 (why I read) organised by AIE (the Italian Publishers Association) of which Pirelli is main partner and that this year focuses on the development of promotional activities and the creation of company and school libraries.

Approximately 3500 books (at the Milan Headquarters and the Bollate Plant) will be made available to employees for lending and reference: titles include the most recent best-sellers, novels, non-fiction, thrillers, science-fiction and much more. The opening of these libraries follows the tradition of Pirelli as promoter of activities aimed at fostering reading and the dissemination of culture at the work place, in the steps of the first library opened in 1928 and the Pirelli Cultural Centre established with the goal of “grouping and coordinating educational activities” that has organised musical events and plays, exhibitions, film festivals and conferences with world-famed writers and artists over the years. The libraries join the one successfully operating at the Pirelli Industrial Hub in Settimo Torinese.

Multimedia

Read more...

Read more...

Read more...

The Pirelli Foundation among the “Open Archives” of the Photography Network

The Pirelli Foundation will take part in the “Archivi Aperti”, an initiative from the “Rete Fotografia” – the foundation is a member from this year – which will take place during the week 21-28 October to promote the awareness and study of the photographic heritage of Milan and Lombardy.

The photographic archives represent an extraordinary resource in terms of historical and cultural testimony: the Milanese territory and the Lombardy region in general have a great deal of organisations involved in the conservation and promotion of these photographic archives. In fact, many other cultural institutions from Lombardy have signed up to the Photography Network – active since 2011 – including the Civic Photography Archive of the Milan City Council, the Museum of Contemporary Photography, the Museum of Science and Technology of Milan, the Milan Triennale Foundation, the Italian Touring Club, the ISEC Foundation, the Fiera Milan Foundation, the Dalmine Foundation and the FORMA Foundation, among others.

For the “Open Archives”, the Pirelli Foundation has announced that on the days of Saturday 22 October (at 2.30pm, 4pm and 5.30pm) and Thursday 27 October (at 5.30pm), special guided tours will be made of three locations: the Pirelli Headquarters with its historic cooling tower, the fourteenth century Bicocca of the Arcimboldi, and the foundation itself with a visit to the historical archive of the company. The guided tours will focus on the photographic heritage: visitors will be able to browse a wide range of documents from the Pirelli photography bank, made up of more than 700,000 pieces, between negatives on plates and film, stamps and slides, the subjects of which are factories, products, exhibitions, fairs, car, motorcycling and cycling races and fashion. Photos – produced or commissioned by the Department of Marketing and Communication between the 1910s and the 1990s – taken to illustrate the company magazines and production catalogues or to be used in Pirelli advertising campaigns. Among the photographers are great names of photography like Federico Patellani, Ugo Mulas, Arno Hammacher, Fulvio Roiter, Aldo Ballo and Gabriele Basilico, and well known agencies such as Publifoto and Farabola. The catalogue of photographs relating to car racing, fashion and exhibitions is currently available online in a dedicated area of our website //search.fondazionepirelli.org/pirelli/fotografico.The projects of the categorisation and digitalisation of the photobank in progress will in the coming months enable the enhancement of the digital catalogue with the publication of new series relating to the construction of the Pirelli skyscraper, cycling races from 1920 to 1951 and the inner workings of the factories from the 1950s and 1960s.

For information and tour bookings: visite@fondazionepirelli.org– tel. 02 64423971

For information on the “Open Archives” calendar: www.retefotografia.it

The Pirelli Foundation will take part in the “Archivi Aperti”, an initiative from the “Rete Fotografia” – the foundation is a member from this year – which will take place during the week 21-28 October to promote the awareness and study of the photographic heritage of Milan and Lombardy.

The photographic archives represent an extraordinary resource in terms of historical and cultural testimony: the Milanese territory and the Lombardy region in general have a great deal of organisations involved in the conservation and promotion of these photographic archives. In fact, many other cultural institutions from Lombardy have signed up to the Photography Network – active since 2011 – including the Civic Photography Archive of the Milan City Council, the Museum of Contemporary Photography, the Museum of Science and Technology of Milan, the Milan Triennale Foundation, the Italian Touring Club, the ISEC Foundation, the Fiera Milan Foundation, the Dalmine Foundation and the FORMA Foundation, among others.

For the “Open Archives”, the Pirelli Foundation has announced that on the days of Saturday 22 October (at 2.30pm, 4pm and 5.30pm) and Thursday 27 October (at 5.30pm), special guided tours will be made of three locations: the Pirelli Headquarters with its historic cooling tower, the fourteenth century Bicocca of the Arcimboldi, and the foundation itself with a visit to the historical archive of the company. The guided tours will focus on the photographic heritage: visitors will be able to browse a wide range of documents from the Pirelli photography bank, made up of more than 700,000 pieces, between negatives on plates and film, stamps and slides, the subjects of which are factories, products, exhibitions, fairs, car, motorcycling and cycling races and fashion. Photos – produced or commissioned by the Department of Marketing and Communication between the 1910s and the 1990s – taken to illustrate the company magazines and production catalogues or to be used in Pirelli advertising campaigns. Among the photographers are great names of photography like Federico Patellani, Ugo Mulas, Arno Hammacher, Fulvio Roiter, Aldo Ballo and Gabriele Basilico, and well known agencies such as Publifoto and Farabola. The catalogue of photographs relating to car racing, fashion and exhibitions is currently available online in a dedicated area of our website //search.fondazionepirelli.org/pirelli/fotografico.The projects of the categorisation and digitalisation of the photobank in progress will in the coming months enable the enhancement of the digital catalogue with the publication of new series relating to the construction of the Pirelli skyscraper, cycling races from 1920 to 1951 and the inner workings of the factories from the 1950s and 1960s.

For information and tour bookings: visite@fondazionepirelli.org– tel. 02 64423971

For information on the “Open Archives” calendar: www.retefotografia.it

Multimedia

Read more...

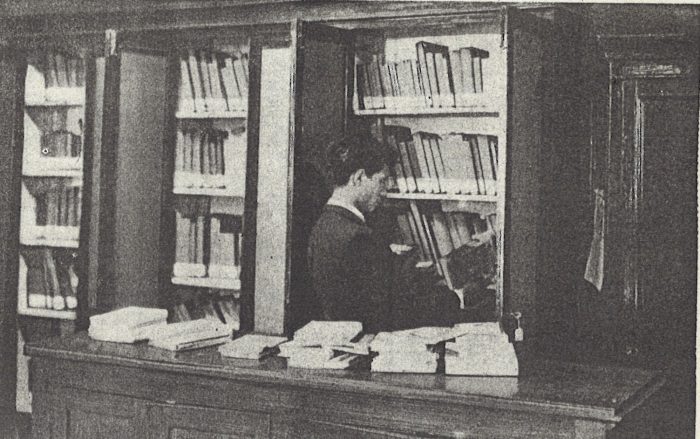

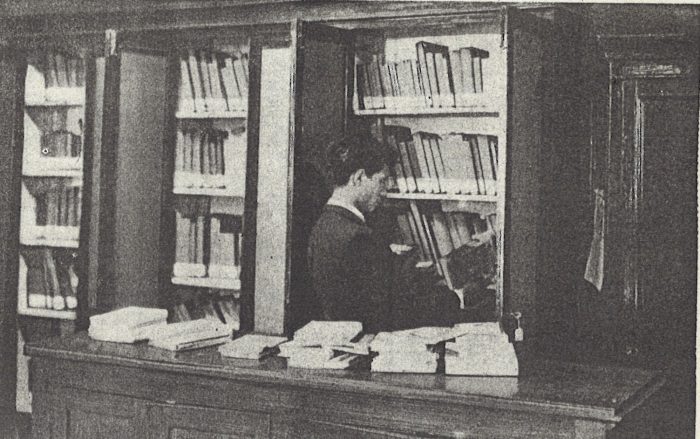

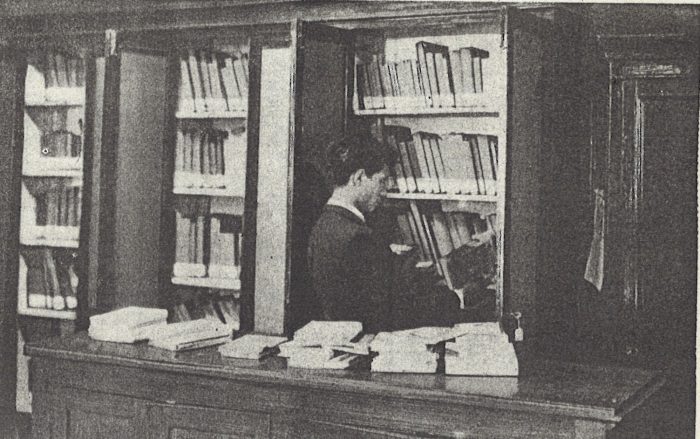

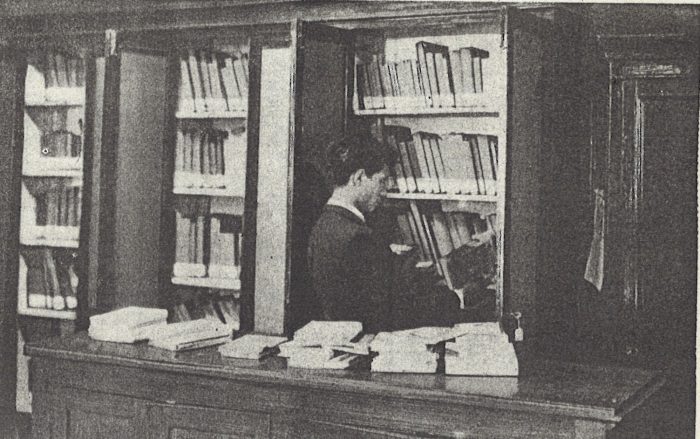

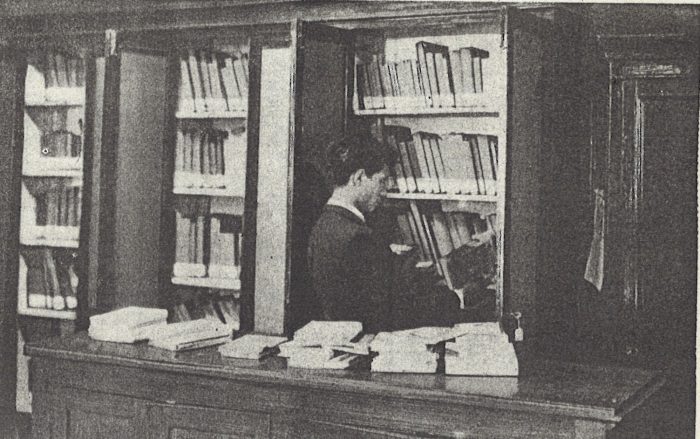

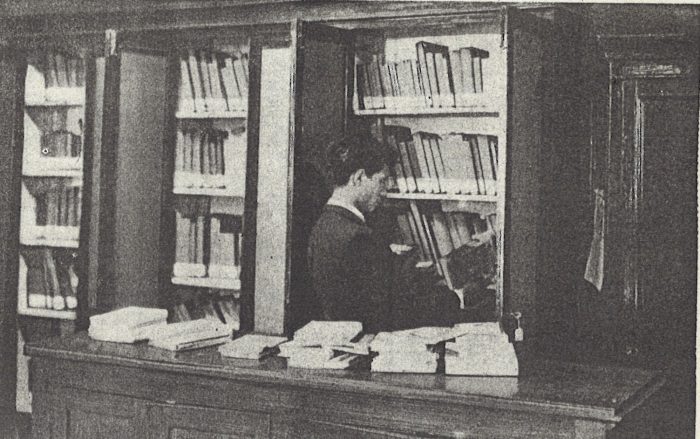

Reading and Pirelli: from the library of the 1920s to the brand new libraries of today

A document from 23 October 1928 conserved in our historical archive makes the first reference to a company library: it describes a travelling library available to staff who have signed up to “After Work for Pirelli Companies”, with 800 books and its own borrowing system. The “Firm, as well as supporting the costs of managing the library, will also contribute to its growth with an annual sum for the acquisition of new works”; book loans were for no longer than 20 days, with a maximum of two books to be borrowed at a time. In the next few years the library found a home at the Bicocca of the Arcimboldi before, after a period of closure during the war, it was reopened in October 1945 in a new location.The “Notiziario Pirelli” of 1 February 1946 referred to the opening of a “Section of our library at Milan-Brusada on the second floor of a building in G.B. Pirelli Road,” with the objective of “Increasing the amount of volumes with appropriate purchases in order to supply everybody with that powerful tool for recreation and education: the book.” .In 1946 there were approximately 3,000 books in the new library, chosen by the workers using catalogues provided by the company. The importance given by Pirelli to the spread of reading among its employees is further evident in the “Notiziaio Pirelli” in a piece titled “The Worker Does Not Read”: “You have to meet the worker after the trials and tribulations of the working day are over and try to improve his home life, creating in him the desire to extend himself beyond the world of the factory.” And it was with this in mind that the Pirelli Centre of Culture was created, from the initiative of the News Report Editorial Board.As Silvestro Severgnini, promoter of the Centre of Culture, relates in Culture is Like Bread (La cultura è come il pane) for the Pirelli Magazine in 1951, the centre was created with the aim of “Bringing together and coordinating the various initiatives, either already present or in the planning stage, and the educational framework relating to our firm, with the goal of raising the average cultural level of the workers.” Among the activities of the centre were not only the “Pirelli library”, but also “factory meetings”, “the internal selection school”, musical and theatrical events, exhibitions, film festivals and conventions to which world famous writers and artists were invited, including Milan Kundera and Cesare Zavattini.

Over the next few years the library would grow to reach 10,000 books by 1956; in 1957 an entire page of “Facts and Information” was dedicated to the renovation of the library, which received a new space at 183 Sarca Avenue, where it stayed until 1972. The newest addition was a reading room dedicated to newspapers and magazines and browsing books directly from the shelves. Library loans rose to 50,000 units, a tangible sign of the interest reading held for many of the employees. In 1972 the company library was transferred from the “Creative Activities” building to building 120, still on Sarca Avenue, where it was provided with an information desk managed by the “Group for Social Activities.” Pirelli also made a Technical-Scientific Library available for its researchers and engineers with around 16,000 books on tyre and cable technology from the nineteenth century until the present day.Since 2010 this library can be found at the Pirelli Foundation

Today, in line with this long tradition and in support of #ioleggoperchè (I read because), an initiative supported by the AIE (Italian Association of Publishers) to promote reading, Pirelli will soon open two new company libraries at the Milan Bicocca Headquarters and in the Bollate factory after the positive experience garnered from the Polo Industriale company library in Settimo Torinese, currently the only private library included in the SBAM (Library System of the Turin Metropolitan Area). The contents of the three company libraries will be supplemented every year with new volumes, including literature books for children.

The same spirit which inspired the first travelling library in 1928 continues today with the opening of these new company libraries, creating a new meeting point where reading is the channel of communication, of exchange and of bringing people together.

A document from 23 October 1928 conserved in our historical archive makes the first reference to a company library: it describes a travelling library available to staff who have signed up to “After Work for Pirelli Companies”, with 800 books and its own borrowing system. The “Firm, as well as supporting the costs of managing the library, will also contribute to its growth with an annual sum for the acquisition of new works”; book loans were for no longer than 20 days, with a maximum of two books to be borrowed at a time. In the next few years the library found a home at the Bicocca of the Arcimboldi before, after a period of closure during the war, it was reopened in October 1945 in a new location.The “Notiziario Pirelli” of 1 February 1946 referred to the opening of a “Section of our library at Milan-Brusada on the second floor of a building in G.B. Pirelli Road,” with the objective of “Increasing the amount of volumes with appropriate purchases in order to supply everybody with that powerful tool for recreation and education: the book.” .In 1946 there were approximately 3,000 books in the new library, chosen by the workers using catalogues provided by the company. The importance given by Pirelli to the spread of reading among its employees is further evident in the “Notiziaio Pirelli” in a piece titled “The Worker Does Not Read”: “You have to meet the worker after the trials and tribulations of the working day are over and try to improve his home life, creating in him the desire to extend himself beyond the world of the factory.” And it was with this in mind that the Pirelli Centre of Culture was created, from the initiative of the News Report Editorial Board.As Silvestro Severgnini, promoter of the Centre of Culture, relates in Culture is Like Bread (La cultura è come il pane) for the Pirelli Magazine in 1951, the centre was created with the aim of “Bringing together and coordinating the various initiatives, either already present or in the planning stage, and the educational framework relating to our firm, with the goal of raising the average cultural level of the workers.” Among the activities of the centre were not only the “Pirelli library”, but also “factory meetings”, “the internal selection school”, musical and theatrical events, exhibitions, film festivals and conventions to which world famous writers and artists were invited, including Milan Kundera and Cesare Zavattini.

Over the next few years the library would grow to reach 10,000 books by 1956; in 1957 an entire page of “Facts and Information” was dedicated to the renovation of the library, which received a new space at 183 Sarca Avenue, where it stayed until 1972. The newest addition was a reading room dedicated to newspapers and magazines and browsing books directly from the shelves. Library loans rose to 50,000 units, a tangible sign of the interest reading held for many of the employees. In 1972 the company library was transferred from the “Creative Activities” building to building 120, still on Sarca Avenue, where it was provided with an information desk managed by the “Group for Social Activities.” Pirelli also made a Technical-Scientific Library available for its researchers and engineers with around 16,000 books on tyre and cable technology from the nineteenth century until the present day.Since 2010 this library can be found at the Pirelli Foundation

Today, in line with this long tradition and in support of #ioleggoperchè (I read because), an initiative supported by the AIE (Italian Association of Publishers) to promote reading, Pirelli will soon open two new company libraries at the Milan Bicocca Headquarters and in the Bollate factory after the positive experience garnered from the Polo Industriale company library in Settimo Torinese, currently the only private library included in the SBAM (Library System of the Turin Metropolitan Area). The contents of the three company libraries will be supplemented every year with new volumes, including literature books for children.

The same spirit which inspired the first travelling library in 1928 continues today with the opening of these new company libraries, creating a new meeting point where reading is the channel of communication, of exchange and of bringing people together.

Multimedia

Read more...

Pirelli and the MITO Festival: Music “At Work”

Pirelli started collaborating with the MITO SettembreMusica Festival back in 2007; a bond in keeping with the custom of consolidating relationship between enterprises and culture that Pirelli has always fostered by promoting artistic, cultural and educational activities.

The tradition runs deep: suffice it to mention that in 1954 the eclectic American music composer John Cage, famous for the composition entitled 4’33” (which are the minutes of silence of the piece), performed at the Pirelli Cultural Centre with David Tudor in a “concerto for prepared pianos”. Screws, metal balls, spoons, clothing pegs, bamboo sticks, clock gears and other objects were applied to the strings of the two pianos to produce unprecedented effects and shock – both positively and negatively – the members of what was said to be “one of the most educated audiences in town”. In this context, Pirelli started promoting the events of the MITO Festival in 2010 in the company’s industrial spaces, to reassert the bond between the places of work and those of music as an expression of the industrial humanism which historically identifies the corporation.

An orchestra pitted against factory spaces in the 2010 edition of the Festival: the old plant in Settimo Torinese hosted “I Fiati di Torino” of the local RAI Symphonic Orchestra. The performance included compositions by Mozart, Bach, Beethoven, Berio, Gabrieli, Saglietti and Stravinskij and was held in front of an audience of over four hundred people.

Following the success of the 2010 edition, musicians returned to the factory for MITO 2011: this time, the “Pomeriggi Musicali” orchestra, conducted by maestro Luca Pfaff, performed in the revamped spaces of the Settimo Torinese Industrial Hub. The programme featured compositions by Darius Milhaud (suite from the ballet “Le boeuf sur le toit”), Artur Honegger (“Pastoral d’été”), Manuel De Falla (suite from the ballet “El Amor Brujo”) and Igor Stravinskij (“Suite for chamber orchestra No. 1 and No. 2″).

In September 2014, instead, the Torino Philharmonic Orchestra performed at the Settimo Torinese Industrial Hub. The musicians conducted by Micha Hamel performed “Symphony No. 1 in C Major, op. 21” and “Symphony No. in A major, op. 92” by Ludwig van Beethoven and were applauded by one thousand people. “La Settima a Settimo” – a play on words: the seventh in Settimo, which in addition to being the name of the town also means “seventh” in Italian – always draws many Pirelli employees.

For the 2016 edition, under the guidance of the new artistic director Nicola Campogrande, Pirelli will be hosting one of the musical appointments this time in the headquarters instead of in the factory. On Sunday 18 September, at 9 p.m., the Auditorium of the HQ1 building – erected around the old cooling tower of the Milano Bicocca plant – will stage of the performance entitled “I figli di Beethoven”: “Altus Trio” will play “Trio in E-flat major, op. 70 n. 2” by Ludwig van Beethoven and “Trio in F major, op. 80” by Robert Schumann.

Pirelli started collaborating with the MITO SettembreMusica Festival back in 2007; a bond in keeping with the custom of consolidating relationship between enterprises and culture that Pirelli has always fostered by promoting artistic, cultural and educational activities.

The tradition runs deep: suffice it to mention that in 1954 the eclectic American music composer John Cage, famous for the composition entitled 4’33” (which are the minutes of silence of the piece), performed at the Pirelli Cultural Centre with David Tudor in a “concerto for prepared pianos”. Screws, metal balls, spoons, clothing pegs, bamboo sticks, clock gears and other objects were applied to the strings of the two pianos to produce unprecedented effects and shock – both positively and negatively – the members of what was said to be “one of the most educated audiences in town”. In this context, Pirelli started promoting the events of the MITO Festival in 2010 in the company’s industrial spaces, to reassert the bond between the places of work and those of music as an expression of the industrial humanism which historically identifies the corporation.

An orchestra pitted against factory spaces in the 2010 edition of the Festival: the old plant in Settimo Torinese hosted “I Fiati di Torino” of the local RAI Symphonic Orchestra. The performance included compositions by Mozart, Bach, Beethoven, Berio, Gabrieli, Saglietti and Stravinskij and was held in front of an audience of over four hundred people.

Following the success of the 2010 edition, musicians returned to the factory for MITO 2011: this time, the “Pomeriggi Musicali” orchestra, conducted by maestro Luca Pfaff, performed in the revamped spaces of the Settimo Torinese Industrial Hub. The programme featured compositions by Darius Milhaud (suite from the ballet “Le boeuf sur le toit”), Artur Honegger (“Pastoral d’été”), Manuel De Falla (suite from the ballet “El Amor Brujo”) and Igor Stravinskij (“Suite for chamber orchestra No. 1 and No. 2″).

In September 2014, instead, the Torino Philharmonic Orchestra performed at the Settimo Torinese Industrial Hub. The musicians conducted by Micha Hamel performed “Symphony No. 1 in C Major, op. 21” and “Symphony No. in A major, op. 92” by Ludwig van Beethoven and were applauded by one thousand people. “La Settima a Settimo” – a play on words: the seventh in Settimo, which in addition to being the name of the town also means “seventh” in Italian – always draws many Pirelli employees.

For the 2016 edition, under the guidance of the new artistic director Nicola Campogrande, Pirelli will be hosting one of the musical appointments this time in the headquarters instead of in the factory. On Sunday 18 September, at 9 p.m., the Auditorium of the HQ1 building – erected around the old cooling tower of the Milano Bicocca plant – will stage of the performance entitled “I figli di Beethoven”: “Altus Trio” will play “Trio in E-flat major, op. 70 n. 2” by Ludwig van Beethoven and “Trio in F major, op. 80” by Robert Schumann.

Multimedia

Read more...

Music and labour: Pirelli-MiTo concerts and the conversation between factory and culture

Building compatible behaviours, bringing people together, tuning instruments. Learning how to aggregate original expressions and dissonance. Making music. Organising labour. Creating symmetry. Building beauty. A product made with the hands or mind. This attempt to draw connections between industry and music, sound and labour, it is audacious? It is difficult, perhaps. But not impossible. If anything , it’s unusual but not audacious. The creativity that connects people and builds communities must always be built.

This is a subject close to Pirelli’s heart. It’s part of the history of the bonds Pirelli has forged between manufacturing and culture, and between technology and artistic narration, using every tool available to it. The advertising illustrators of old. Painters. Writers. Poets. Architects. Artists. Photographers. People of words and machines. Invoking essential values. The quality of work and interpersonal relations. The joy of a hard-working community that is receptive to research and change.

Let’s make music our focus this time. Let’s tell why Pirelli is resuming its partnership with MiTo. And why concerts are returning to the workplace, on the factory floor at Settimo Torinese industrial park in 2010, 2011 and 2014 and now at Pirelli HQ in Milan, to relive, and of course, also to renew, that sense of deep-rooted tradition.

We’ll see labour and its “sound”, the evocation of 19th century soundscapes (the “industrial century”), meticulous execution, and the pursuit of perfection all return as the same central themes as previous concerts. All summed up in a simple phrase: to produce, and to do it well. Finding and creating original, new harmonies. A challenge in constant evolution.

Pirelli has renewed its commitment to another of its self-imposed obligations: to restore music to its central role in popular culture, aware that people have never stopped loving classical music and, if anything, the younger generations in particular, are eager for more open, intense relations, charged with inventive and emotion. MiTo has always been central to this. The choice of Beethoven and his “sons”, starting with Schumann, are proof-positive of this: music that is not limited to the Baroque tradition of a violin, violoncello and piano trio and which gives form to the surge of what was once romantic modernity, in the innovative “counterpointing” and in the creation of chords narrating change in the world, heralding evolutions on the horizon. Extraordinary creativity. And meticulous execution. Times past and times future, just like we said. Metamorphosis. Once again, industry breeds culture and champions all that is contemporary.

Where shall we start our exploration? From skills with something in common. The skills of manufacturing and machines. And of philosophical reasoning, as it seeks original interpretations to make sense of the complexities of society and evolving markets. And of the stories they tell. The skills to be found in R&D labs, where the grounds are laid for new products and new production, distribution and consumer systems. The skills of artistic creativity.

Worthy of note is sociologist Aldo Bonomi, for example, an exponent of “molecular capitalism theory”, of the “infinite city”, a world crammed with intelligent and far-reaching manufacturing and service networks, of “In-finite capitalism”, in the transition from post-Fordism to fragmentation and the “liquid labour swamp”: for a recovery to be made, “made in Italy” must be replaced with “remade in Italy”, and a fourth season inaugurated, in the wake of the cottage industry, factories and business parks. Supply chains must enter an era in which the host territory becomes a source of value, held aloft as a common asset to be regenerated and no longer treated as merely a repository of knowledge, traditions and resources to be extracted, or contemplated purely in terms of growth of the quantitative kind, founded on local consumption and social dumping. It should be an era that recognizes the social and cooperative nature of investment in the knowledge economy. A world in which manufacturing, in order to rebuild the value base, must pollinate industrial culture with the scientific and social skills propagated by the creative in our society, professionals, young “digital natives”. In turn, if their investment in vocational development is to translate into work and an associated income, they can no longer harbour the utopian idea of virtual and deindustrialised capitalism.” In other words, there must be a fusion of different skills within the production system. And dialogue between an industry’s inner and outer worlds.

This could also said in another way, using the “Milano Steam” acronym for example. Assolombarda, Lombardy’s association of industries, decided to use the word Steam to represent the fusion of the city’s manufacturing and creative sectors, borrowing the initial letters of Science, Technology, Engineering and Environment (the sustainable environment), and Arts. The latter comprises the collective knowledge of the humanities, an area in which Italy excels, and manufacturing, also referred to as “the beautiful factory” of the high-tech industry in which creativity, research, production, and services measure their competitiveness against the exceptional ability to “make beautiful things that the world finds beautiful.” Milan is therefore a paradigm for Italy, a country in which social capital, economic capital, scientific capital and aesthetic capital play as a team in the development game. Can all this be conveyed in a single word? “Harmony” – a musical word – might work.

This brings us back to the issue of dialogues between an industry’s inner and outer worlds, from Pirelli’s experiential perspective. How about another example? First, there are the workplaces animated by philosophical and scientific debate, as was the case when, in June 2013, Pirelli hosted a section of the “Milanesiana” in the group’s Bicocca HQ Auditorium. Directed by Elisabetta Sgarbi, the central theme of the concert was “Philosophy, Cinema, Secret” and welcomed among its cast Massimo Cacciari, Remo Bodei, Umberto Veronesi, Marco Bellocchio, Tzevan Todorov and Emanuele Severino. Or we might want to mention the frequent sharing of experiences between artists working on giant installations in the HangarBicocca and Pirelli engineers and technicians working in Pirelli labs. Or the positive conversations between writers and artists to illustrate and enrich Pirelli’s annual accounts. Or the factory music events (more about that in a second) held in Pirelli’s Settimo Torinese site, an industrial complex whose infrastructure and research labs were designed by Renzo Piano around the “beautiful factory” concept. The complex is in green belt territory (hence the nickname with obvious literary charm: “the factory in the cherry garden”) making it a transparent, safe, pleasant and ecologically forward-thinking location. Or industry itself, and the material it provides for industrial narratives that form the basis of books and theatrical productions (such as the collaboration with Mondadori and Laterza, or with Piccolo Teatro di Milano, on “Settimo – La fabbrica e il lavoro” directed by Serena Sinigaglia and performed to a full house at Piccolo Teatro almost every night for three weeks in 2012). Or even the didactic exhibitions and projects that Pirelli Foundation has run in schools across Milan for thousand of pupils, in an effort to reaffirm and renew links between industry and education, labour and professional development. In each, there is an intermingling of knowledge and perspectives, and the questions raised by differing cultures are met with answers offering a wealth of “cross-fertilizations”.

It is intense stuff. The intention is to improve the quality of city life, seen as a place of visionary thinking and high-end production, within the context of the knowledge economy and, as suggested earlier, industry seen as the fulcrum of responsible development. It is another way of bringing business culture to the community and experiencing industry as a place of culture, open to culture and manufacturer of culture. It all amounts to a larger-than-life “manufacturing renaissance”, as it was so brilliantly named at a recent Aspen Institute Italia seminar held in the Bicocca Villa degli Arcimboldi. The event produced a very successful publication offering much food for thought on the subject of good business culture.

As we’ve said, modern businesses need a modern, namely new, culture. Something that echoes the making of products and the making of music, which brings us full circle. Tuning and harmonizing. Learning how to bring together consonances and, it goes without saying, also dissonances. Original harmonies. And discords which recompose.

It is a cultural proposition of fascinating proportions, and also the subject of a very useful book for men and women whose job has to do with industry: “Yes to the Mess: Surprising Leadership Lessons from Jazz” by Frank J. Barrett (the Italian translation has a wonderful and very insightful introduction by Severino Salvemini). What makes the book so interesting are the two identities Barrett occupies: management lecturer at Harvard and jazz pianist. Equally compelling are how his thoughts move confidently across the many levels at which the best business cultures manage to exist. Organisation and improvisation. Team play and the creative talent of the soloist. The repetition of a familiar note. The courage to break away from established patterns and explore new rhythms. Research and innovation, in other words. Built on a solid base of instrumental technique.

The ideas presented are recurring themes in the constant positing of ideas to find the most imaginative relations between industry and culture. Not to mention ever present in the attempt to make sense of the “industrial metamorphosis” that demands we continually seek new paradigms in order to change how we conceptualise production, products and consumption. In changing times, if we are to respond to the Great Crisis, we must be impartial about organisational forms and the relations between the people in them. Music, or jazz as we discussed, provide some answers. Really? Salvemini explains, “New business management models must be based on examples taken from new contexts which are less rigid than traditional ones.” The great historical examples of Miles Davis, Louis Armstrong, Charlie Parker and, more recently, the great Keith Jarrett, tell us that a great soloist needs the accompaniment of solid rhythm sections, a supporting orchestra or of a group of some kind (a trio, a quartet, etc.) able to anticipate, provoke, or to follow the soloist’s trumpet or piano: “The group supports its leader,” Salvemini insists, “as should also happen in an organisation in which cohesion and harmony reign.”

To be prolific, cultures need contrast. Or better still: they need hybridisation. This means the combination of languages, techniques, behaviours and ways of working. The mixing of words about doing and telling. Of machines, people, production and products. However you approach it, music is the perfect interpretative, and even narrative, tool.

Want more proof? Well, how about the experience of a string ensemble, the Italian Chamber Orchestra directed by Salvatore Accardo, an outstanding violinist of international standing who held two concert rehearsals a year, before going on tour, in the Pirelli HQ Auditorium in Milan. The rehearsals were open to all employees who used their break to check for themselves, in a live performance, what “playing a concert” and “building an execution” really mean. The performance sparked many conversations. About work. What it sounds like. About music. Not to mention the work that goes into playing it, the search for perfection (a common experience, known to both violinist and engineer, for whom Accardo was the ultimate ambassador during Pirelli’s Quality Week, in front of an audience of production engineers and people. ) Produce, but do it well. Find and create original, new harmonies. That’s good business, isn’t it?

There’s another option in this ongoing intrigue, which is to renew the current calibre of classical music. And tie concerts, symphonies, sonatas to workplaces to produce “high” culture that is, at the same time, popular, as well as the extraordinary dimension of a highly original symphony, in which Italian culture, throughout the 20th century, gave Europe a constant supply of innovative elaboration and original fusions.

This is the sense, then, of the by now long-standing relationship between a grand Italian and international organisation and the Verdi Orchestra, one of Milan’s leading international companies. And also with the Scala theatre, in a long season of its lifetime. Through such a prestigious a festival as MiTo Settembre Musica (nearly four weeks of concerts in Milan and Turin, for which there has often been, and still is, an active collaboration with Pirelli Foundation.)

The value of factory concerts, like the ones held in the Settimo Torinese industrial complex (the last one was 19 September 2014) where thousands of people gave the Turin Philharmonic Orchestra, directed by Micha Hamel, a standing ovation for its performance of two Beethoven symphonies, the First and Seventh, can’t be emphasized enough. “La Settima a Settimo” – Beethoven’s masterpiece, his 7th symphony ”, as it was so brilliantly called. Beethoven played with robots worked and research labs buzzed in Pirelli’s cutting-edge plant. Incidentally, Europe has a tradition of tying music to places of work. Take the workers’ concerts of 20th century Vienna: classical performances were played to new audiences, spectators who were not traditional middle-class concert-goers, and the compositions were at, for that period, contemporary (just one example: Mahler’s symphonies directed by the young Webern.) This was also the Italy of the 60s and 70s, and the work of musicians like Luigi Nono, Claudio Abbado and Maurizio Pollini , who used their different sensibilities and experiences to “illuminate the factory”.

[Best_Wordpress_Gallery id=”41″ gal_title=”MIto 2014″]

There is a deep bond, after all, between doing business responsibly and making music. Central to the issue are themes like work and what it sounds like, the effort of execution, the pursuit of perfection, in the knowledge that factories are made of people at work, gestures of agile, able hands and the movements of machines. Factories are rhythm. Voices and noises. Noises which become sounds. Factories have their own music. And music can enter factories. Industries have their own culture. And culture can, indeed it must, find a place in industry. In short? Produce, but do it well. Find and create original, new harmonies.

Which brings us back to the combination of tradition and innovation. The choice of Beethoven (for the September 2014 concert) is proof-positive of this: his music has firm roots in the best 18th century canon; he interprets a lively romantic modernity and represents the monumental status of “classical” while also foreshadowing compositions to come many decades after him. Extraordinary creativity. And meticulous orchestration.

The location selected is also hugely significant. After the Great Crisis, industry resumed its place at the heart of the economy. The Settimo facility is proof of how factories have changed and developed, with the adoption of sophisticated technologies. Metamorphosis. Industry breeds culture and champions all that is contemporary. “Staging a concert in a factory,” said director Micha Hamel, orchestra director of the “Settima a Settimo” concert, “is a singular experience and also a sign that something new is taking place. Music is entering an unusual place. Boundaries are being broken. Artistically speaking, it is a very important concept.”

It was precisely this realization that inspired the entire music-in-a-factory experience. From the very first concert, back on 13 September 2010, in the old Pirelli plant on the eve of its closure (to give way to the new complex). On the stage were the Turin Wind Ensemble and musicians from the Rai Torinese Symphonic Orchestra. In the background were tyres produced in the plant. In the audience, the industrial forecourt, were more than four hundred people. All there to hear music by Mozart, Bach and Beethoven, Berio and Gabrieli, Saglietti and Stravinsky: music from the 1700s to modern-day. Double the significance: of sound and place. It was a concert for brass, the instruments echoing the metal, a symbolic relation to the metal used to make cars. It was a game of harmonies, evoking what work can and should be, even when the harmony is difficult to achieve.

[Best_Wordpress_Gallery id=”42″ gal_title=”MIto 2010″]

Now that latest generation technologies make the workplace a more varied, rich and complex place, music can find a new space, and a more intense contemporary role. Bringing classical back. And adding original evocations to the contemporary. Innovation is also a language.

At the second concert, held on 9 September 2011, the orchestra was the Pomeriggi Musicali di Milano, directed by Luca Pfaff. The venue was the large warehouse space in the new industrial complex. The sounds of machines at work, a faint echo, could be heard in the distance. It was a factory after all. Playing to an audience of 700 people, the orchestra performed Stravinsky, Milhaud, Honegger and De Falla. It was the music of the 1900s. The century of great change. And of industry, a complexity that monopolized innovation, caused serious upheaval, involved millions of men and women: a world of brand-new responsibilities, struggles to take centre stage and the reclaiming of rights and obligations. The 20th century was all about words, pictures and movement. Noises -and sounds – that had never been heard before. Literature, figurative art, music were deconstructed then put back together again. Classic forms faded from existence. Research was the new form, and it has continued into our present, uncertain age.

[Best_Wordpress_Gallery id=”38″ gal_title=”Mito 2011″]

To reflect upon the 20th century, with the music it brought to the factory floor, means more than just critically examining our recent origins; it also means trying to build a new epistemology of post-modernity, and tracing a futuristic map of a better future. To chart a world in movement. Listening to music helps, it can bring comprehension to the deep sense of change, both in work and in its associated relations. Business culture is building a theme tune, starting from the notes of Beethoven at the Settimo concert. Classic symphony and contemporary presence.

Contemporary presence, of course. We see it again in the MiTo theme for 2016: “Fathers and sons”, or rather, Beethoven and Schumann in the Auditorium concert. It is a theme to be re-explored and revisited, a baton being passed, from the “classical” to the experimentation which prefigured the decompositions of the 20th century. Times past and times future. And metamorphosis. As applied to creation; to narration; to labour. Besides, it’s what our laborious, controversial, painful modernity is made of: metamorphosis. But it’s happy, too, in the sparks, as it looks to the future.

Building compatible behaviours, bringing people together, tuning instruments. Learning how to aggregate original expressions and dissonance. Making music. Organising labour. Creating symmetry. Building beauty. A product made with the hands or mind. This attempt to draw connections between industry and music, sound and labour, it is audacious? It is difficult, perhaps. But not impossible. If anything , it’s unusual but not audacious. The creativity that connects people and builds communities must always be built.

This is a subject close to Pirelli’s heart. It’s part of the history of the bonds Pirelli has forged between manufacturing and culture, and between technology and artistic narration, using every tool available to it. The advertising illustrators of old. Painters. Writers. Poets. Architects. Artists. Photographers. People of words and machines. Invoking essential values. The quality of work and interpersonal relations. The joy of a hard-working community that is receptive to research and change.

Let’s make music our focus this time. Let’s tell why Pirelli is resuming its partnership with MiTo. And why concerts are returning to the workplace, on the factory floor at Settimo Torinese industrial park in 2010, 2011 and 2014 and now at Pirelli HQ in Milan, to relive, and of course, also to renew, that sense of deep-rooted tradition.

We’ll see labour and its “sound”, the evocation of 19th century soundscapes (the “industrial century”), meticulous execution, and the pursuit of perfection all return as the same central themes as previous concerts. All summed up in a simple phrase: to produce, and to do it well. Finding and creating original, new harmonies. A challenge in constant evolution.

Pirelli has renewed its commitment to another of its self-imposed obligations: to restore music to its central role in popular culture, aware that people have never stopped loving classical music and, if anything, the younger generations in particular, are eager for more open, intense relations, charged with inventive and emotion. MiTo has always been central to this. The choice of Beethoven and his “sons”, starting with Schumann, are proof-positive of this: music that is not limited to the Baroque tradition of a violin, violoncello and piano trio and which gives form to the surge of what was once romantic modernity, in the innovative “counterpointing” and in the creation of chords narrating change in the world, heralding evolutions on the horizon. Extraordinary creativity. And meticulous execution. Times past and times future, just like we said. Metamorphosis. Once again, industry breeds culture and champions all that is contemporary.

Where shall we start our exploration? From skills with something in common. The skills of manufacturing and machines. And of philosophical reasoning, as it seeks original interpretations to make sense of the complexities of society and evolving markets. And of the stories they tell. The skills to be found in R&D labs, where the grounds are laid for new products and new production, distribution and consumer systems. The skills of artistic creativity.

Worthy of note is sociologist Aldo Bonomi, for example, an exponent of “molecular capitalism theory”, of the “infinite city”, a world crammed with intelligent and far-reaching manufacturing and service networks, of “In-finite capitalism”, in the transition from post-Fordism to fragmentation and the “liquid labour swamp”: for a recovery to be made, “made in Italy” must be replaced with “remade in Italy”, and a fourth season inaugurated, in the wake of the cottage industry, factories and business parks. Supply chains must enter an era in which the host territory becomes a source of value, held aloft as a common asset to be regenerated and no longer treated as merely a repository of knowledge, traditions and resources to be extracted, or contemplated purely in terms of growth of the quantitative kind, founded on local consumption and social dumping. It should be an era that recognizes the social and cooperative nature of investment in the knowledge economy. A world in which manufacturing, in order to rebuild the value base, must pollinate industrial culture with the scientific and social skills propagated by the creative in our society, professionals, young “digital natives”. In turn, if their investment in vocational development is to translate into work and an associated income, they can no longer harbour the utopian idea of virtual and deindustrialised capitalism.” In other words, there must be a fusion of different skills within the production system. And dialogue between an industry’s inner and outer worlds.

This could also said in another way, using the “Milano Steam” acronym for example. Assolombarda, Lombardy’s association of industries, decided to use the word Steam to represent the fusion of the city’s manufacturing and creative sectors, borrowing the initial letters of Science, Technology, Engineering and Environment (the sustainable environment), and Arts. The latter comprises the collective knowledge of the humanities, an area in which Italy excels, and manufacturing, also referred to as “the beautiful factory” of the high-tech industry in which creativity, research, production, and services measure their competitiveness against the exceptional ability to “make beautiful things that the world finds beautiful.” Milan is therefore a paradigm for Italy, a country in which social capital, economic capital, scientific capital and aesthetic capital play as a team in the development game. Can all this be conveyed in a single word? “Harmony” – a musical word – might work.

This brings us back to the issue of dialogues between an industry’s inner and outer worlds, from Pirelli’s experiential perspective. How about another example? First, there are the workplaces animated by philosophical and scientific debate, as was the case when, in June 2013, Pirelli hosted a section of the “Milanesiana” in the group’s Bicocca HQ Auditorium. Directed by Elisabetta Sgarbi, the central theme of the concert was “Philosophy, Cinema, Secret” and welcomed among its cast Massimo Cacciari, Remo Bodei, Umberto Veronesi, Marco Bellocchio, Tzevan Todorov and Emanuele Severino. Or we might want to mention the frequent sharing of experiences between artists working on giant installations in the HangarBicocca and Pirelli engineers and technicians working in Pirelli labs. Or the positive conversations between writers and artists to illustrate and enrich Pirelli’s annual accounts. Or the factory music events (more about that in a second) held in Pirelli’s Settimo Torinese site, an industrial complex whose infrastructure and research labs were designed by Renzo Piano around the “beautiful factory” concept. The complex is in green belt territory (hence the nickname with obvious literary charm: “the factory in the cherry garden”) making it a transparent, safe, pleasant and ecologically forward-thinking location. Or industry itself, and the material it provides for industrial narratives that form the basis of books and theatrical productions (such as the collaboration with Mondadori and Laterza, or with Piccolo Teatro di Milano, on “Settimo – La fabbrica e il lavoro” directed by Serena Sinigaglia and performed to a full house at Piccolo Teatro almost every night for three weeks in 2012). Or even the didactic exhibitions and projects that Pirelli Foundation has run in schools across Milan for thousand of pupils, in an effort to reaffirm and renew links between industry and education, labour and professional development. In each, there is an intermingling of knowledge and perspectives, and the questions raised by differing cultures are met with answers offering a wealth of “cross-fertilizations”.

It is intense stuff. The intention is to improve the quality of city life, seen as a place of visionary thinking and high-end production, within the context of the knowledge economy and, as suggested earlier, industry seen as the fulcrum of responsible development. It is another way of bringing business culture to the community and experiencing industry as a place of culture, open to culture and manufacturer of culture. It all amounts to a larger-than-life “manufacturing renaissance”, as it was so brilliantly named at a recent Aspen Institute Italia seminar held in the Bicocca Villa degli Arcimboldi. The event produced a very successful publication offering much food for thought on the subject of good business culture.

As we’ve said, modern businesses need a modern, namely new, culture. Something that echoes the making of products and the making of music, which brings us full circle. Tuning and harmonizing. Learning how to bring together consonances and, it goes without saying, also dissonances. Original harmonies. And discords which recompose.

It is a cultural proposition of fascinating proportions, and also the subject of a very useful book for men and women whose job has to do with industry: “Yes to the Mess: Surprising Leadership Lessons from Jazz” by Frank J. Barrett (the Italian translation has a wonderful and very insightful introduction by Severino Salvemini). What makes the book so interesting are the two identities Barrett occupies: management lecturer at Harvard and jazz pianist. Equally compelling are how his thoughts move confidently across the many levels at which the best business cultures manage to exist. Organisation and improvisation. Team play and the creative talent of the soloist. The repetition of a familiar note. The courage to break away from established patterns and explore new rhythms. Research and innovation, in other words. Built on a solid base of instrumental technique.

The ideas presented are recurring themes in the constant positing of ideas to find the most imaginative relations between industry and culture. Not to mention ever present in the attempt to make sense of the “industrial metamorphosis” that demands we continually seek new paradigms in order to change how we conceptualise production, products and consumption. In changing times, if we are to respond to the Great Crisis, we must be impartial about organisational forms and the relations between the people in them. Music, or jazz as we discussed, provide some answers. Really? Salvemini explains, “New business management models must be based on examples taken from new contexts which are less rigid than traditional ones.” The great historical examples of Miles Davis, Louis Armstrong, Charlie Parker and, more recently, the great Keith Jarrett, tell us that a great soloist needs the accompaniment of solid rhythm sections, a supporting orchestra or of a group of some kind (a trio, a quartet, etc.) able to anticipate, provoke, or to follow the soloist’s trumpet or piano: “The group supports its leader,” Salvemini insists, “as should also happen in an organisation in which cohesion and harmony reign.”

To be prolific, cultures need contrast. Or better still: they need hybridisation. This means the combination of languages, techniques, behaviours and ways of working. The mixing of words about doing and telling. Of machines, people, production and products. However you approach it, music is the perfect interpretative, and even narrative, tool.

Want more proof? Well, how about the experience of a string ensemble, the Italian Chamber Orchestra directed by Salvatore Accardo, an outstanding violinist of international standing who held two concert rehearsals a year, before going on tour, in the Pirelli HQ Auditorium in Milan. The rehearsals were open to all employees who used their break to check for themselves, in a live performance, what “playing a concert” and “building an execution” really mean. The performance sparked many conversations. About work. What it sounds like. About music. Not to mention the work that goes into playing it, the search for perfection (a common experience, known to both violinist and engineer, for whom Accardo was the ultimate ambassador during Pirelli’s Quality Week, in front of an audience of production engineers and people. ) Produce, but do it well. Find and create original, new harmonies. That’s good business, isn’t it?

There’s another option in this ongoing intrigue, which is to renew the current calibre of classical music. And tie concerts, symphonies, sonatas to workplaces to produce “high” culture that is, at the same time, popular, as well as the extraordinary dimension of a highly original symphony, in which Italian culture, throughout the 20th century, gave Europe a constant supply of innovative elaboration and original fusions.

This is the sense, then, of the by now long-standing relationship between a grand Italian and international organisation and the Verdi Orchestra, one of Milan’s leading international companies. And also with the Scala theatre, in a long season of its lifetime. Through such a prestigious a festival as MiTo Settembre Musica (nearly four weeks of concerts in Milan and Turin, for which there has often been, and still is, an active collaboration with Pirelli Foundation.)

The value of factory concerts, like the ones held in the Settimo Torinese industrial complex (the last one was 19 September 2014) where thousands of people gave the Turin Philharmonic Orchestra, directed by Micha Hamel, a standing ovation for its performance of two Beethoven symphonies, the First and Seventh, can’t be emphasized enough. “La Settima a Settimo” – Beethoven’s masterpiece, his 7th symphony ”, as it was so brilliantly called. Beethoven played with robots worked and research labs buzzed in Pirelli’s cutting-edge plant. Incidentally, Europe has a tradition of tying music to places of work. Take the workers’ concerts of 20th century Vienna: classical performances were played to new audiences, spectators who were not traditional middle-class concert-goers, and the compositions were at, for that period, contemporary (just one example: Mahler’s symphonies directed by the young Webern.) This was also the Italy of the 60s and 70s, and the work of musicians like Luigi Nono, Claudio Abbado and Maurizio Pollini , who used their different sensibilities and experiences to “illuminate the factory”.

[Best_Wordpress_Gallery id=”41″ gal_title=”MIto 2014″]

There is a deep bond, after all, between doing business responsibly and making music. Central to the issue are themes like work and what it sounds like, the effort of execution, the pursuit of perfection, in the knowledge that factories are made of people at work, gestures of agile, able hands and the movements of machines. Factories are rhythm. Voices and noises. Noises which become sounds. Factories have their own music. And music can enter factories. Industries have their own culture. And culture can, indeed it must, find a place in industry. In short? Produce, but do it well. Find and create original, new harmonies.

Which brings us back to the combination of tradition and innovation. The choice of Beethoven (for the September 2014 concert) is proof-positive of this: his music has firm roots in the best 18th century canon; he interprets a lively romantic modernity and represents the monumental status of “classical” while also foreshadowing compositions to come many decades after him. Extraordinary creativity. And meticulous orchestration.

The location selected is also hugely significant. After the Great Crisis, industry resumed its place at the heart of the economy. The Settimo facility is proof of how factories have changed and developed, with the adoption of sophisticated technologies. Metamorphosis. Industry breeds culture and champions all that is contemporary. “Staging a concert in a factory,” said director Micha Hamel, orchestra director of the “Settima a Settimo” concert, “is a singular experience and also a sign that something new is taking place. Music is entering an unusual place. Boundaries are being broken. Artistically speaking, it is a very important concept.”

It was precisely this realization that inspired the entire music-in-a-factory experience. From the very first concert, back on 13 September 2010, in the old Pirelli plant on the eve of its closure (to give way to the new complex). On the stage were the Turin Wind Ensemble and musicians from the Rai Torinese Symphonic Orchestra. In the background were tyres produced in the plant. In the audience, the industrial forecourt, were more than four hundred people. All there to hear music by Mozart, Bach and Beethoven, Berio and Gabrieli, Saglietti and Stravinsky: music from the 1700s to modern-day. Double the significance: of sound and place. It was a concert for brass, the instruments echoing the metal, a symbolic relation to the metal used to make cars. It was a game of harmonies, evoking what work can and should be, even when the harmony is difficult to achieve.

[Best_Wordpress_Gallery id=”42″ gal_title=”MIto 2010″]

Now that latest generation technologies make the workplace a more varied, rich and complex place, music can find a new space, and a more intense contemporary role. Bringing classical back. And adding original evocations to the contemporary. Innovation is also a language.

At the second concert, held on 9 September 2011, the orchestra was the Pomeriggi Musicali di Milano, directed by Luca Pfaff. The venue was the large warehouse space in the new industrial complex. The sounds of machines at work, a faint echo, could be heard in the distance. It was a factory after all. Playing to an audience of 700 people, the orchestra performed Stravinsky, Milhaud, Honegger and De Falla. It was the music of the 1900s. The century of great change. And of industry, a complexity that monopolized innovation, caused serious upheaval, involved millions of men and women: a world of brand-new responsibilities, struggles to take centre stage and the reclaiming of rights and obligations. The 20th century was all about words, pictures and movement. Noises -and sounds – that had never been heard before. Literature, figurative art, music were deconstructed then put back together again. Classic forms faded from existence. Research was the new form, and it has continued into our present, uncertain age.

[Best_Wordpress_Gallery id=”38″ gal_title=”Mito 2011″]

To reflect upon the 20th century, with the music it brought to the factory floor, means more than just critically examining our recent origins; it also means trying to build a new epistemology of post-modernity, and tracing a futuristic map of a better future. To chart a world in movement. Listening to music helps, it can bring comprehension to the deep sense of change, both in work and in its associated relations. Business culture is building a theme tune, starting from the notes of Beethoven at the Settimo concert. Classic symphony and contemporary presence.

Contemporary presence, of course. We see it again in the MiTo theme for 2016: “Fathers and sons”, or rather, Beethoven and Schumann in the Auditorium concert. It is a theme to be re-explored and revisited, a baton being passed, from the “classical” to the experimentation which prefigured the decompositions of the 20th century. Times past and times future. And metamorphosis. As applied to creation; to narration; to labour. Besides, it’s what our laborious, controversial, painful modernity is made of: metamorphosis. But it’s happy, too, in the sparks, as it looks to the future.

Read more...

Pirelli and the five Circles

Friday, August 5: official opening of the XXXI Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro. Traditionally engaged in all sport disciplines, Pirelli has always enjoyed a particularly fruitful relationship with the Olympics. Many athletes have competed using equipment made by Pirelli, several advertising have been inspired by the Olympics, a famous calendar was dedicated to the Games – and some Olympic champions were Pirelli employees. One of these – maybe the greatest of all – was London ’48 gold medallist Adolfo Consolini.

Adolfo Consolini’s gold discus

The London Olympics, 2 August 1948. With a distance of 52.23 metres, Italian athlete Adolfo Consolini won the discus throwing gold medal: he was at the pinnacle of a career which would make him one of the greatest Italian sportsmen of all times. When he was not donning the blue jersey of team Italy, “gentle giant” Consolini was training on the Pro Patria field opposite the Bicocca plant wearing the Pirelli Sports Group uniform with the stretched P emblem. Four Olympic Games, three world records, Italian record holder for 17 years, 375 competitions won in a thirty-year-long career: discus thrower Adolfo Consolini put the stamp of the stretched P on the Olympic Five Circles for ever.

Rubber at the Olympic Games in Rome

Sports and correlated events fostered the production of new rubber items and novel building materials for erecting new sports facilities. For the 1960 Olympics in Rome, Pirelli was involved in the building of the Corso Francia flyover, connecting the Flaminio bridge to the stadium area with the installation of 1200 “Cargo” neoprene rubber blocks. The floors of the Swimming Stadium at the Foro Italico and some interiors of the Palazzo dello Sport indoor arena were covered with “Miplac” flooring made by Linoleum. The large airport terminal in Rome, opened for the occasion, was equipped with 230 square metres of “Afolin” soundproofing panels and 32,585 square metres of rubber floors to welcome the world’s athletes.

The Olympic cartoons Babbut, Mammut and Figliut

The July 1964 cover of “Pivendere” – the Pirelli newsletter dedicated to retailers – showed an clumsy Olympic athlete attempting a pole vault jump which will probably end in disaster. The athlete was Babbut, the blundering caveman who with his wife Mammut and child Figliut had been appearing in the hugely popular Pirelli TV commercials for several years. All not-so-young Italians will remember the cartoon starring a quintessentially Milanese traffic warden (turned referee in the Olympics version) who at the end cautioned the three troublemakers declaring “ué cavernicoli, non siamo più all’età della pietra!” (“Ohi, cavemen, this isn’t the Stone Age any more!”) going on to explain that in modern times Pirelli has invented foam rubber and Sempione tyres with safety sidewall.

Carl Lewis’ magic rubber foot

When photographer Annie Leibowitz famously depicted him at the starting blocks of the 100 metres race in red pumps for the “Power is nothing without control” campaign in 1994, Carl Lewis was one of greatest Olympians of all times. Long jump and running were the disciplines in which King Carl won it all: four gold medals in Los Angeles ’84, two golds and one silver in Seoul ’88 and two more golds in Barcelona ’92. He would take gold medal number nine four years later, in Atlanta in ’96. Four Olympics, ten medals: Pirelli was closely linked to the Son of the Wind’s relationship with the Five Circles.

In 1997, Carl Lewis passed Pirelli’s ideal Olympic baton to the French track and field sprinter Marie-José Pérec. She continued the race started by the Son of the Wind in the commercial directed by Gerard de Thame, sprinting across glaciers and volcanoes, on water and sand, chased by frightening special-effects monsters. She ultimately escaped by jumping onto the top of the Totem Pole, the majestic stone column in Monument Valley, Utah. Once again, like Carl Lewis before her, she had wings on her feet and could rely on Pirelli treads. And Marie-José had shown the world that she really did have wings on her feet at the Olympic Games in Barcelona 1992 when she took the 400 metre gold, and again in Atlanta 1996, winning the 200 and 400 metre races. So, once again in 1997, an Olympian at the pinnacle of her career reminded the world that “Power is nothing without control”.

The artist’s return to Olympia

Created by Arthur Elgort and shot in Siviglia, the 1990 calendar was a celebration of Olympia and its physicality, naturally all in female form. Track, fencing, discus and javelin throwing, archery and relay, with the Olympic flame on the highest step of the podium: the arena walls were grey and gigantic, the race was dusty. The prize, a laurel wreath. The athletes of the 1990 Pirelli calendar wore simple loincloths decorated with cryptic symbols that one may be led to believe tell the legendary story of Olympia and the Games. Unknown to most, it was the tread pattern of the Pirelli P600 tyre.

Friday, August 5: official opening of the XXXI Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro. Traditionally engaged in all sport disciplines, Pirelli has always enjoyed a particularly fruitful relationship with the Olympics. Many athletes have competed using equipment made by Pirelli, several advertising have been inspired by the Olympics, a famous calendar was dedicated to the Games – and some Olympic champions were Pirelli employees. One of these – maybe the greatest of all – was London ’48 gold medallist Adolfo Consolini.

Adolfo Consolini’s gold discus

The London Olympics, 2 August 1948. With a distance of 52.23 metres, Italian athlete Adolfo Consolini won the discus throwing gold medal: he was at the pinnacle of a career which would make him one of the greatest Italian sportsmen of all times. When he was not donning the blue jersey of team Italy, “gentle giant” Consolini was training on the Pro Patria field opposite the Bicocca plant wearing the Pirelli Sports Group uniform with the stretched P emblem. Four Olympic Games, three world records, Italian record holder for 17 years, 375 competitions won in a thirty-year-long career: discus thrower Adolfo Consolini put the stamp of the stretched P on the Olympic Five Circles for ever.

Rubber at the Olympic Games in Rome

Sports and correlated events fostered the production of new rubber items and novel building materials for erecting new sports facilities. For the 1960 Olympics in Rome, Pirelli was involved in the building of the Corso Francia flyover, connecting the Flaminio bridge to the stadium area with the installation of 1200 “Cargo” neoprene rubber blocks. The floors of the Swimming Stadium at the Foro Italico and some interiors of the Palazzo dello Sport indoor arena were covered with “Miplac” flooring made by Linoleum. The large airport terminal in Rome, opened for the occasion, was equipped with 230 square metres of “Afolin” soundproofing panels and 32,585 square metres of rubber floors to welcome the world’s athletes.

The Olympic cartoons Babbut, Mammut and Figliut

The July 1964 cover of “Pivendere” – the Pirelli newsletter dedicated to retailers – showed an clumsy Olympic athlete attempting a pole vault jump which will probably end in disaster. The athlete was Babbut, the blundering caveman who with his wife Mammut and child Figliut had been appearing in the hugely popular Pirelli TV commercials for several years. All not-so-young Italians will remember the cartoon starring a quintessentially Milanese traffic warden (turned referee in the Olympics version) who at the end cautioned the three troublemakers declaring “ué cavernicoli, non siamo più all’età della pietra!” (“Ohi, cavemen, this isn’t the Stone Age any more!”) going on to explain that in modern times Pirelli has invented foam rubber and Sempione tyres with safety sidewall.

Carl Lewis’ magic rubber foot

When photographer Annie Leibowitz famously depicted him at the starting blocks of the 100 metres race in red pumps for the “Power is nothing without control” campaign in 1994, Carl Lewis was one of greatest Olympians of all times. Long jump and running were the disciplines in which King Carl won it all: four gold medals in Los Angeles ’84, two golds and one silver in Seoul ’88 and two more golds in Barcelona ’92. He would take gold medal number nine four years later, in Atlanta in ’96. Four Olympics, ten medals: Pirelli was closely linked to the Son of the Wind’s relationship with the Five Circles.

In 1997, Carl Lewis passed Pirelli’s ideal Olympic baton to the French track and field sprinter Marie-José Pérec. She continued the race started by the Son of the Wind in the commercial directed by Gerard de Thame, sprinting across glaciers and volcanoes, on water and sand, chased by frightening special-effects monsters. She ultimately escaped by jumping onto the top of the Totem Pole, the majestic stone column in Monument Valley, Utah. Once again, like Carl Lewis before her, she had wings on her feet and could rely on Pirelli treads. And Marie-José had shown the world that she really did have wings on her feet at the Olympic Games in Barcelona 1992 when she took the 400 metre gold, and again in Atlanta 1996, winning the 200 and 400 metre races. So, once again in 1997, an Olympian at the pinnacle of her career reminded the world that “Power is nothing without control”.

The artist’s return to Olympia

Created by Arthur Elgort and shot in Siviglia, the 1990 calendar was a celebration of Olympia and its physicality, naturally all in female form. Track, fencing, discus and javelin throwing, archery and relay, with the Olympic flame on the highest step of the podium: the arena walls were grey and gigantic, the race was dusty. The prize, a laurel wreath. The athletes of the 1990 Pirelli calendar wore simple loincloths decorated with cryptic symbols that one may be led to believe tell the legendary story of Olympia and the Games. Unknown to most, it was the tread pattern of the Pirelli P600 tyre.

Multimedia

Read more...