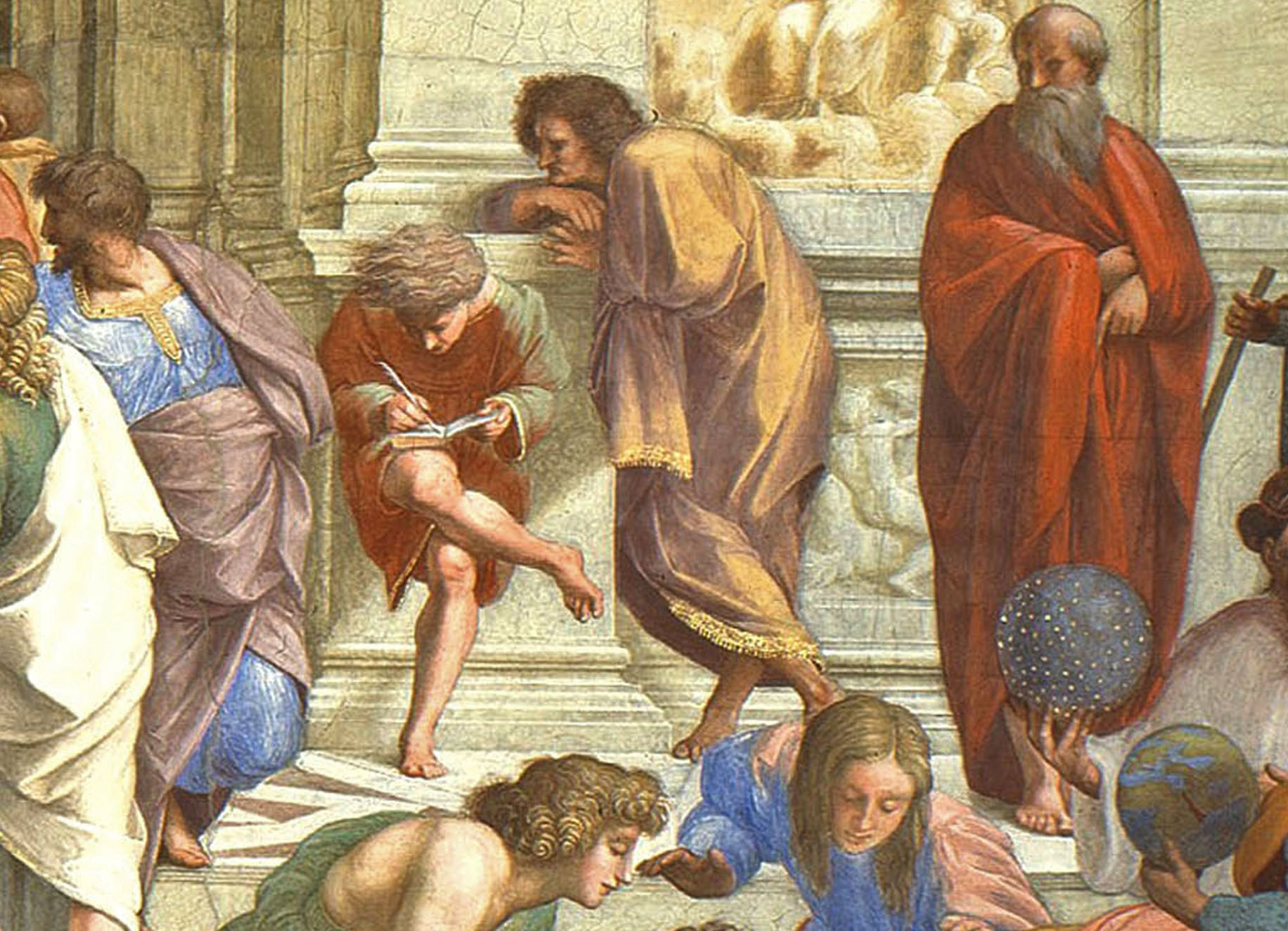

A rushing wind ruffles his hair. But it does not disturb his concentration. He stands leaning against the wall with his legs crossed to improve his balance. He writes with his face bent over the notebook resting above his knee, holding the pen firmly to give the words and perhaps the drawings all the attention they deserve.

He is little more than a boy: a student, a young man in the court, an aspiring artist or scientist. And he seems heedless of the world around him. Yet what surrounds him is a solemn world: philosophers, mathematicians and scientists; a convergence of knowledge; a metaphor for wisdom; with man at the centre.

This is ‘The School of Athens’, the great fresco painted by Raphael in the early 16th century in the Stanza della Segnatura, one of the four Vatican Rooms inside the Apostolic Palaces (the preparatory cartoon, as fascinating as the finest examples of creative processes, adorns one of the most important rooms in the Ambrosiana in Milan). It is a masterpiece of the Renaissance and a symbol of a world rooted in great classical culture, thus enabling it to offer a vision of a future rooted in beauty and reason. A ‘temple of Philosophy’, to quote an idea of Marsilio Ficino, a wise interpreter of Humanism.

In the centre, at the top of a wide staircase, are Aristotle and Plato, surrounded by disciples, both real and imagined, intent on discussing astronomy, geometry, celestial spaces and the whirlwind of ideas. Among those present are Zeno, Epicurus, Euclid and perhaps Archimedes, as well as two contemporary figures of the time. Michelangelo, somewhat separated from the group, is pensive and distracted by the drawing he is sketching. He is solitary and shadowy, as he was in life, a master annoyed by his contemporaries and his own pupils. And Raphael, who, almost in profile and from above, takes pleasure in such a gathering of intellects (he himself is therefore a ‘master’ in that gathering). There is conflict between the artists, but they also represent different conceptions of life and art, between torment and the sublime.

And what about that nervous boy writing in the wind? Nothing is known about him. Neither Vasari nor other critics and historians have ever posed the question of who he was or why a breath of wind crept through his hair.

However, things are ever-changing. That scribe boy, taken from Raphael’s fresco, now takes centre stage on the two covers, one in yellow-red and the other in blue-violet, of ‘Use Your Illusion’, the double album released by Guns N’ Roses in September 1991. Among other tracks (such as the famous ‘Don’t cry’ and ‘Live and let die’) the album features one of the most intense versions of ‘Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door’, the poignant song written by Bob Dylan in 1973 for the soundtrack of Sam Peckinpah’s Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, an elegy to the death of Sheriff Baker — a good man and far from the stereotypical Western hero. Like so many of us, he was overwhelmed by history, knowing how to make good use of his illusions, and as the sun of life set, he knocked on the gates of Paradise, seeking peace — precisely the peace that our uncertain and controversial times do not seem to grant us. Despite the humanistic promises of the wise domain of knowledge and the subsequent enlightenment hopes of the triumph of reason, that Raphael boy brought back to life by Guns N’ Roses speaks to us today, as then, of restlessness and a never-ending need for signs to translate and appease it: of paintings and wise words.

The interplay between Renaissance painting and contemporary stadium rock emerged from a conversation with Ugo Loeser, the astute banker CEO of Arca Fondi. The occasion was the presentation of Patrizia Fontana‘s insightful book, Dai forma al tuo talento (Embrace your talent) (Franco Angeli Editore), which discusses the challenges and aspirations of a new generation searching for fulfilment, both personal and professional.

A survey carried out by ‘Talent in Motion’ between January and February 2025 among 1,600 young adults (aged 20 to 30, 86% of whom had a university degree) showed that 80% of respondents were afraid of failure and of disappointing themselves and others. Almost all of them considered ‘success’ to be ‘important’ (85%), yet 75% were afraid of ‘making the wrong career choices’, and 78% confessed that they didn’t know which path to take in the current context of job uncertainty. Furthermore, 76% reported feeling anxious in the face of competition.

This generation is experiencing a dramatic crisis of confidence. They are in a constant state of acute concern about the disturbing interplay between general geopolitical and economic tensions, and a lack of confidence in their own abilities and the good use of their ‘talent’.

This level of uncertainty undermines the possibility of building a future, the sense of community and the very foundations of the market economy and liberal democracy, and it demands answers.

From this perspective, Patrizia Fontana’s use of the word ‘talent’ is reminiscent of the Gospel parable of the same name. In the parable, a master entrusts his wealth to his servants before going on a journey. He distributes different amounts to each servant based on their abilities. Upon his return, he assesses their stewardship, rewarding those who invested wisely and increased their talents, and rebuking the one who hid his out of fear. If that talent is not only understood in a narrow monetary sense, then the parable’s reference takes on an even broader cultural and ethical scope. It points to the personal and social qualities that can be employed to overcome fears and thus strengthen the common good and ‘public goods’.

How? As well as looking inward, it is necessary to learn to evaluate the contexts in which one’s choices will fit and the conditions in which one will be operating. Study history, geography, politics, economics, social situations, and changes in the scientific and technological landscape well. In times of such radical, rapid and sweeping changes to market structures and, more broadly, socio-economic balances, it is necessary to adopt a flexible and unprejudiced attitude in order to study and adapt to new developments. Skills are needed, of course. But above all, you need a robust and ambitious inclination towards knowledge, the basis of which is knowing how to ask questions. As good teachers suggest, one must ‘learn to learn’.

In short, we must contribute to the creation of new cognitive maps by following the clear path indicated by the leaders of corporate culture for some time now. We must value a ‘polytechnic culture’ that links humanistic and scientific knowledge, the sense of beauty deeply rooted in Italian culture, and the inclination towards originality, resourcefulness, and innovation. We must also recognise the importance of historical awareness and the ability to think of ‘stories for the future’. However, when insisting on the ‘future of memory’, we must be mindful of Leonardo Sciascia’s warning in his collection of essays ‘To Future Memory (If Memory Has a Future…)’.

A lesson in ‘industrial humanism’, indeed. It is precisely the structure of these algorithms and the construction of these now widespread artificial intelligence mechanisms that tells us we need a multidisciplinary approach involving cyberscience, physics, mathematics, statistics, engineering, sociology, philosophy, psychology, economics and law to understand their meaning and value, and to govern their dynamics and consequences.

This is a critical culture, therefore, as a horizon of knowledge and as an ethical standpoint, and it is precisely with the new generations that we must insist on this. With the young people who continue to ask our parents’ and grandparents’ generations questions about meaning and value construction.

We have an obligation to try to provide answers that inspire confidence in the future. This is also to avoid falling into the trap of Narcissus, a negative myth and symbol of death (the character drowns in his fatal admiration of his reflection in the water), and nihilism — the complete opposite of the widespread need for creativity, community, and why not, competitiveness (which, let us remember, comes from the Latin ‘cum’ and ‘petere’, meaning ‘moving together towards a shared horizon’). We must also avoid becoming prey to real technological solitude, where one engages in dialogue with AI for feedback without realising that one is not facing ‘the gaze of the other’ with which to construct one’s own, albeit problematic, identity, but rather the manipulation of a deceptive mirror.

And so we return to the restlessness and redemptive writing of Raphael’s boy, a representation of each one of us and our honest and sincere attempts to shape our destiny, still letting the wind ruffle his hair and his ideas. Remembering Bob Dylan again, ‘Blowin’ in the Wind’, indeed.

(photo: Getty Images)

A rushing wind ruffles his hair. But it does not disturb his concentration. He stands leaning against the wall with his legs crossed to improve his balance. He writes with his face bent over the notebook resting above his knee, holding the pen firmly to give the words and perhaps the drawings all the attention they deserve.

He is little more than a boy: a student, a young man in the court, an aspiring artist or scientist. And he seems heedless of the world around him. Yet what surrounds him is a solemn world: philosophers, mathematicians and scientists; a convergence of knowledge; a metaphor for wisdom; with man at the centre.

This is ‘The School of Athens’, the great fresco painted by Raphael in the early 16th century in the Stanza della Segnatura, one of the four Vatican Rooms inside the Apostolic Palaces (the preparatory cartoon, as fascinating as the finest examples of creative processes, adorns one of the most important rooms in the Ambrosiana in Milan). It is a masterpiece of the Renaissance and a symbol of a world rooted in great classical culture, thus enabling it to offer a vision of a future rooted in beauty and reason. A ‘temple of Philosophy’, to quote an idea of Marsilio Ficino, a wise interpreter of Humanism.

In the centre, at the top of a wide staircase, are Aristotle and Plato, surrounded by disciples, both real and imagined, intent on discussing astronomy, geometry, celestial spaces and the whirlwind of ideas. Among those present are Zeno, Epicurus, Euclid and perhaps Archimedes, as well as two contemporary figures of the time. Michelangelo, somewhat separated from the group, is pensive and distracted by the drawing he is sketching. He is solitary and shadowy, as he was in life, a master annoyed by his contemporaries and his own pupils. And Raphael, who, almost in profile and from above, takes pleasure in such a gathering of intellects (he himself is therefore a ‘master’ in that gathering). There is conflict between the artists, but they also represent different conceptions of life and art, between torment and the sublime.

And what about that nervous boy writing in the wind? Nothing is known about him. Neither Vasari nor other critics and historians have ever posed the question of who he was or why a breath of wind crept through his hair.

However, things are ever-changing. That scribe boy, taken from Raphael’s fresco, now takes centre stage on the two covers, one in yellow-red and the other in blue-violet, of ‘Use Your Illusion’, the double album released by Guns N’ Roses in September 1991. Among other tracks (such as the famous ‘Don’t cry’ and ‘Live and let die’) the album features one of the most intense versions of ‘Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door’, the poignant song written by Bob Dylan in 1973 for the soundtrack of Sam Peckinpah’s Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, an elegy to the death of Sheriff Baker — a good man and far from the stereotypical Western hero. Like so many of us, he was overwhelmed by history, knowing how to make good use of his illusions, and as the sun of life set, he knocked on the gates of Paradise, seeking peace — precisely the peace that our uncertain and controversial times do not seem to grant us. Despite the humanistic promises of the wise domain of knowledge and the subsequent enlightenment hopes of the triumph of reason, that Raphael boy brought back to life by Guns N’ Roses speaks to us today, as then, of restlessness and a never-ending need for signs to translate and appease it: of paintings and wise words.

The interplay between Renaissance painting and contemporary stadium rock emerged from a conversation with Ugo Loeser, the astute banker CEO of Arca Fondi. The occasion was the presentation of Patrizia Fontana‘s insightful book, Dai forma al tuo talento (Embrace your talent) (Franco Angeli Editore), which discusses the challenges and aspirations of a new generation searching for fulfilment, both personal and professional.

A survey carried out by ‘Talent in Motion’ between January and February 2025 among 1,600 young adults (aged 20 to 30, 86% of whom had a university degree) showed that 80% of respondents were afraid of failure and of disappointing themselves and others. Almost all of them considered ‘success’ to be ‘important’ (85%), yet 75% were afraid of ‘making the wrong career choices’, and 78% confessed that they didn’t know which path to take in the current context of job uncertainty. Furthermore, 76% reported feeling anxious in the face of competition.

This generation is experiencing a dramatic crisis of confidence. They are in a constant state of acute concern about the disturbing interplay between general geopolitical and economic tensions, and a lack of confidence in their own abilities and the good use of their ‘talent’.

This level of uncertainty undermines the possibility of building a future, the sense of community and the very foundations of the market economy and liberal democracy, and it demands answers.

From this perspective, Patrizia Fontana’s use of the word ‘talent’ is reminiscent of the Gospel parable of the same name. In the parable, a master entrusts his wealth to his servants before going on a journey. He distributes different amounts to each servant based on their abilities. Upon his return, he assesses their stewardship, rewarding those who invested wisely and increased their talents, and rebuking the one who hid his out of fear. If that talent is not only understood in a narrow monetary sense, then the parable’s reference takes on an even broader cultural and ethical scope. It points to the personal and social qualities that can be employed to overcome fears and thus strengthen the common good and ‘public goods’.

How? As well as looking inward, it is necessary to learn to evaluate the contexts in which one’s choices will fit and the conditions in which one will be operating. Study history, geography, politics, economics, social situations, and changes in the scientific and technological landscape well. In times of such radical, rapid and sweeping changes to market structures and, more broadly, socio-economic balances, it is necessary to adopt a flexible and unprejudiced attitude in order to study and adapt to new developments. Skills are needed, of course. But above all, you need a robust and ambitious inclination towards knowledge, the basis of which is knowing how to ask questions. As good teachers suggest, one must ‘learn to learn’.

In short, we must contribute to the creation of new cognitive maps by following the clear path indicated by the leaders of corporate culture for some time now. We must value a ‘polytechnic culture’ that links humanistic and scientific knowledge, the sense of beauty deeply rooted in Italian culture, and the inclination towards originality, resourcefulness, and innovation. We must also recognise the importance of historical awareness and the ability to think of ‘stories for the future’. However, when insisting on the ‘future of memory’, we must be mindful of Leonardo Sciascia’s warning in his collection of essays ‘To Future Memory (If Memory Has a Future…)’.

A lesson in ‘industrial humanism’, indeed. It is precisely the structure of these algorithms and the construction of these now widespread artificial intelligence mechanisms that tells us we need a multidisciplinary approach involving cyberscience, physics, mathematics, statistics, engineering, sociology, philosophy, psychology, economics and law to understand their meaning and value, and to govern their dynamics and consequences.

This is a critical culture, therefore, as a horizon of knowledge and as an ethical standpoint, and it is precisely with the new generations that we must insist on this. With the young people who continue to ask our parents’ and grandparents’ generations questions about meaning and value construction.

We have an obligation to try to provide answers that inspire confidence in the future. This is also to avoid falling into the trap of Narcissus, a negative myth and symbol of death (the character drowns in his fatal admiration of his reflection in the water), and nihilism — the complete opposite of the widespread need for creativity, community, and why not, competitiveness (which, let us remember, comes from the Latin ‘cum’ and ‘petere’, meaning ‘moving together towards a shared horizon’). We must also avoid becoming prey to real technological solitude, where one engages in dialogue with AI for feedback without realising that one is not facing ‘the gaze of the other’ with which to construct one’s own, albeit problematic, identity, but rather the manipulation of a deceptive mirror.

And so we return to the restlessness and redemptive writing of Raphael’s boy, a representation of each one of us and our honest and sincere attempts to shape our destiny, still letting the wind ruffle his hair and his ideas. Remembering Bob Dylan again, ‘Blowin’ in the Wind’, indeed.

(photo: Getty Images)