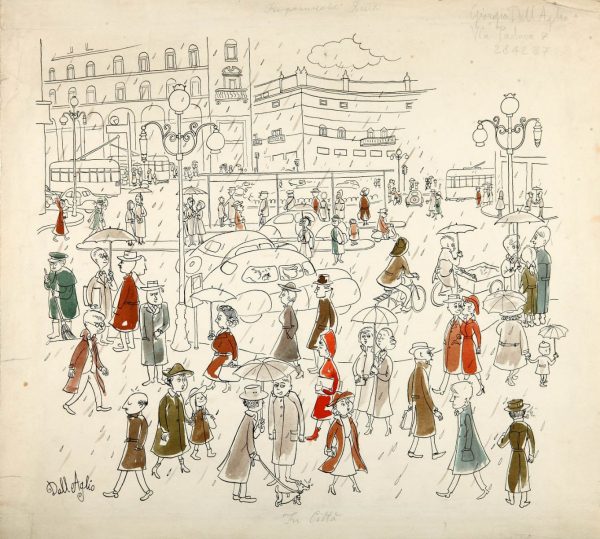

Opening up the factories. Making them visible to citizens, to students, to those who live in industrial areas and to all those who have only ever heard stories about them (and often poor ones, with negative features). And bringing them to life, for one day, in public, for what they are: positive places for work and personal relationships, where production machinery and research laboratories live side by side, hi-tech robots alongside lathes belonging to the ancient mechanical tradition, computers alongside equipment used by highly-skilled manual artisans, canteens alongside libraries. Factories which speak about hard work and invention, remuneration and well-being, often contrasting interests and social inclusion (people grow up, in a factory, and build their careers very often based on merit and ability, independently of any personal characteristics of race, culture, religion, gender or beliefs). Factories, civil places. In an Italy which, notwithstanding the crisis, remains the second-ranking manufacturing country in Europe, immediately after Germany: a record which is to be applauded and reinforced.

“Open factories” is a clever initiative which was initiated years ago at Federchimica (it allowed thousands of Italians to understand that the chemical industry is altogether different from something dirty, dangerous and polluting, but rather is a leading player for the right sort of sustainable economic development, including from an environmental perspective). And, over time, there have been several industries from the Veneto, Piedmont and Lombardy regions which have dedicated a major commitment to “open factories”. Many companies now hold an “Open Day”, when the plants and offices are open to the relatives and children of employees.

Now, in Milan, we have the launch of “Open production facilities”, on the initiative of the City Council and with the collaboration of seventy businesses, including industrial companies, laboratories, workshops and artisanal boutiques, makerspaces, scientific museums, research centres and “Fab Labs”: on 29th September will be held “a day of guided tours, workshops and meetings designed to discover the places where they make the objects which are highly sought after throughout the world under the “made in Italy” banner. An appointment conceived and desired by the Milan City Council with a view to bringing its citizens, youngsters and students closer to the old and new ways of manufacturing whilst at the same time highlighting the value of the great wealth of artisanal knowledge of yesterday and today which is present in this city”.

The assessment is by Cristina Tajani, councillor for Policies for Work, Productive activities, Trade, Fashion and Design. Who insists: “It is important, for the people of Milan, to see what happens behind the scenes of an industrial or artisanal creation. And for us administrators this constitutes a building block for the “Milan Manufacturing” programme which is intended to incentivise a return of “light manufacturing” to the city, with the objective of regenerating decommissioned areas and creating good jobs, allowing so many youngsters to transform their own creativity into ideas, projects and objects thanks to the ever wider use of new technologies, from 3D printers to laser cutters which render the creation of prototypes simpler and more economical”.

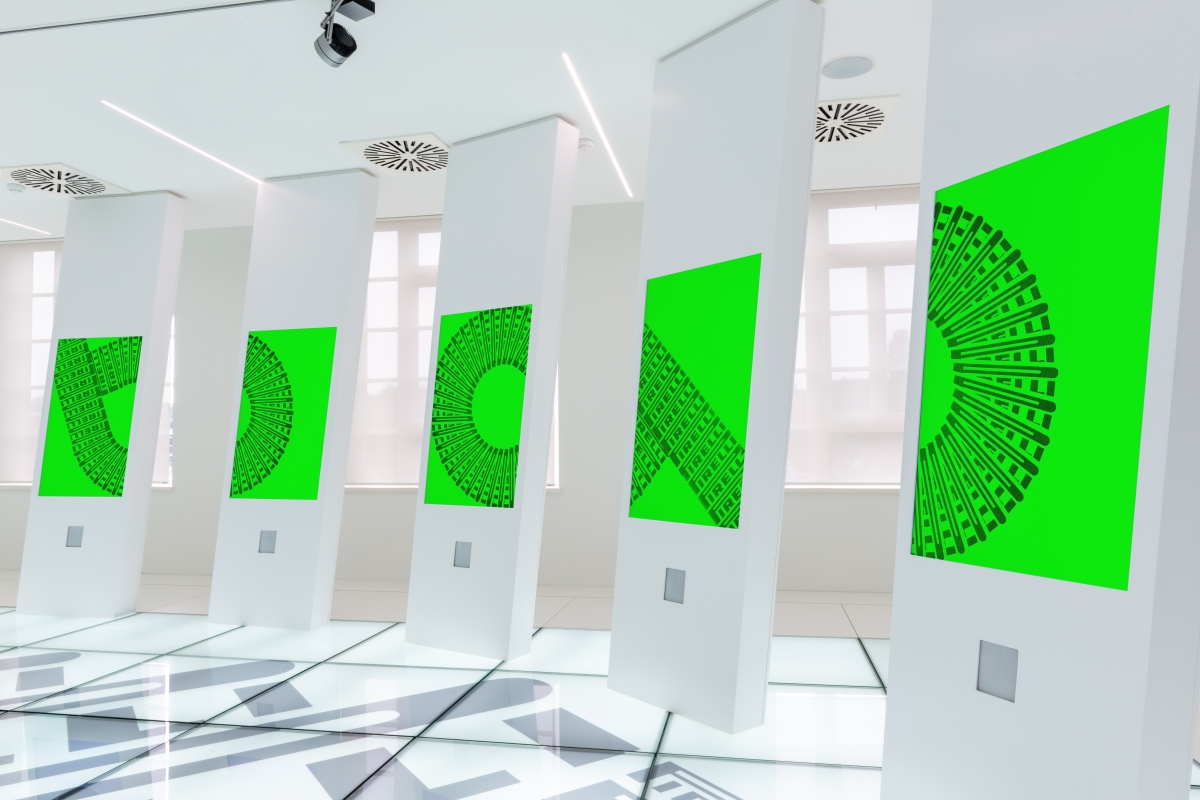

What shall we be able to see, in the seventy places where they “make things, and make them well”, in the factories, large and small, in which that type of entrepreneurship so typical of the history and current affairs of Milan is flourishing? Councillor Tajani explains: “From the laboratory which makes hats for the English royals to the factory which creates aluminium guitars for rock idols such as Lou Reed and Ben Harper, via the Pirelli laboratories where they create those legendary Formula 1 tyres, across to the mechanical workshop where they build by hand and with the assistance of new 3D printers the components needed to bring life back to classical one-off models, or discovering the secrets of the bookbinder’s art or how a ring is created in a goldsmith’s laboratory or how a pair of hand-made shoes is made”.

The full list of participants in the event can be found at www.manifattura.milano.it. Here at Pirelli, in particular, the programme for 29th September includes guided tours of the laboratories for research, development and experimentation in the Bicocca Headquarters, where it will be possible to see how a prototype tyre is created, by combining innovative technologies with manual expertise, and to witness several tests among those used by Pirelli to develop road and racing tyres. An Italian level of excellence of international value.

Milan, the greater Milan of the whole metropolitan area, undergoing a transformation into a smart city on a global scale, is still an industrial city, in which manufacturing accounts for 29% of GDP (Gross Domestic Product), much more in fact than the national average (17%) but also more than the German average (22%). And this is manufacturing undergoing major change, at the heart of a true digital turning point for the economy, according to the criteria of “Industry 4.0”: manufacturing is combining with hi-tech services, sophisticated production capabilities are improving their own competitiveness thanks to a robust contribution from research centres, industrial competencies are being reinforced thanks to the support of the “knowledge economy” strengthened by universities (the Polytechnic university, Bocconi, Cattolica, Statale, Bicocca, Humanitas) which are achieving notable rankings among the best international centres for training and research. The mechanical sector is becoming the mechatronic sector, we are achieving high levels of productivity in rubber and plastics, automotive, chemicals and pharmaceuticals, life sciences and indeed in the traditional “Made in Italy” sectors – clothing and fashion, furnishings and the food and agriculture industry. Industrial Milan means avant-garde modernity and the possibility of a good future.

Stefano Micelli, an economist who is attentive to all the phenomena of “Industry 4.0”, and chair of the Milan Manufacturing Advisory Board, maintains: “Visiting workplaces and manufacturing sites allows people to discover the vitality and quality of the many businesses and artisanal workers that give life to the city of Milan. The purpose of the event is to create an ever greater awareness about the economic and cultural wealth which these activities represent and to underline their growth potential. The initiative is aimed especially at those youngsters who are looking for job opportunities at the current time: the manufacturing sector which is active in the city needs their talent in order to develop design and technological innovation”.

Culture, technology, economic development. As is explained by Marco Taisch, Scientific Chairman of the “World Manufacturing Forum” (the Foundation which promotes it is a prime example of collaboration between businesses, the academic world, institutions and the associative world in order to cultivate and disseminate culture across the manufacturing sector): “Manufacturing is the primary generator of wealth and social equilibrium, as a means to the further development of advanced economies and also as a fundamental tool for the growth of less developed areas of the world”. The Annual Meeting in Cernobbio of the “World Manufacturing Forum”, programmed for 27th and 28th September (in collaboration with the Chamber of Commerce of Milan, the Assolombarda association, the Confartigianato artisan confederation, ANCE and a series of other business and research organisations), will attempt to “determine and influence, at a European and global level, scenarios for the future, by looking into the significance of the innovations which from the manufacturer will also have an impact on services as well as on people’s lives. For these reasons, the twinning of “Open production facilities” and the WMF constitutes a natural partnership based on the sharing of objectives to be achieved together through the exploitation and development of urban and regional manufacturing in an international perspective”.

Especially on Pirelli’s part, there is particular attention placed on the connections between manufacturing and digital processes. The whole Group has for many years followed the processes which lead in this direction, in the context of a “polytechnical culture” which interprets innovation as a general commitment which links together products, productive processes, materials, industrial relations, and the languages of research, of marketing and of communication. And significant indications of this can also be found in a document which brings together company results and indicative forecasts: the Consolidated Accounts 2017.

Pirelli’s digital transformation, in the Accounts, is set alongside five stories of “artisans 4.0” who have taken advantage of digital transformation to find the key to increasing their own activities (we shall discuss these in more detail shortly).And the heading is exemplary: “Data meets passion”, to confirm and re-launch the company’s tradition of explaining the accounts over and above the numbers by referring to art and literature. On this occasion the artistic and cultural contributions, in order to show how the digital world radically changes cultures and customs within society and within individuals, are those of the artist Emiliano Ponzi and of three writers of international renown: Mohsin Hamid, Tom McCarty and Ted Chiang. And these are the stories of the five digital artists, with business ideas reinforced by advanced technological models: the “3Bee” (a hi-tech beehive which, through sensors, monitors the entire production cycle of the hive including remotely), “Alter Ego” (thanks to 3D software it produces ecologically sustainable made-to-measure surf boards), “Demeter.life” (by utilising blockchain technology a direct relationship is established between consumers and farmers throughout the world in order to improve sustainable crops), the “Druetta Upholstery” (the re-launch of the family business using 3D planning and virtual rooms for the design of made-to-measure furnishings) and “Differenthood” (an on-line platform where, based on 5 thousand fabrics and with over 1 billion possible combinations, people can create garments which are unique and 100% Made in Italy, and which can then be shared with the community).

There is then, in the Pirelli Consolidated Accounts 2017, alongside the company data, a general indication about the values of “making things”, in the digital world. And there is the story-telling. With strong literary and political implications. As Tom McCarthy confirms: “within the rise of the digital culture…. it is politics which becomes a literary matter. Literary in the sense that public life – and private life – finds itself governed by its own transcription: when everything is noted down in a register of some sort, then experience as such, and with it the problem of free will (are we masters of ourselves? Or are all our actions and our decisions governed and decided by algorithms?), is reduced to instances and acts of scripture”.

The summary? Open production facilities, precisely. And words to continue to make them live on.

Opening up the factories. Making them visible to citizens, to students, to those who live in industrial areas and to all those who have only ever heard stories about them (and often poor ones, with negative features). And bringing them to life, for one day, in public, for what they are: positive places for work and personal relationships, where production machinery and research laboratories live side by side, hi-tech robots alongside lathes belonging to the ancient mechanical tradition, computers alongside equipment used by highly-skilled manual artisans, canteens alongside libraries. Factories which speak about hard work and invention, remuneration and well-being, often contrasting interests and social inclusion (people grow up, in a factory, and build their careers very often based on merit and ability, independently of any personal characteristics of race, culture, religion, gender or beliefs). Factories, civil places. In an Italy which, notwithstanding the crisis, remains the second-ranking manufacturing country in Europe, immediately after Germany: a record which is to be applauded and reinforced.

“Open factories” is a clever initiative which was initiated years ago at Federchimica (it allowed thousands of Italians to understand that the chemical industry is altogether different from something dirty, dangerous and polluting, but rather is a leading player for the right sort of sustainable economic development, including from an environmental perspective). And, over time, there have been several industries from the Veneto, Piedmont and Lombardy regions which have dedicated a major commitment to “open factories”. Many companies now hold an “Open Day”, when the plants and offices are open to the relatives and children of employees.

Now, in Milan, we have the launch of “Open production facilities”, on the initiative of the City Council and with the collaboration of seventy businesses, including industrial companies, laboratories, workshops and artisanal boutiques, makerspaces, scientific museums, research centres and “Fab Labs”: on 29th September will be held “a day of guided tours, workshops and meetings designed to discover the places where they make the objects which are highly sought after throughout the world under the “made in Italy” banner. An appointment conceived and desired by the Milan City Council with a view to bringing its citizens, youngsters and students closer to the old and new ways of manufacturing whilst at the same time highlighting the value of the great wealth of artisanal knowledge of yesterday and today which is present in this city”.

The assessment is by Cristina Tajani, councillor for Policies for Work, Productive activities, Trade, Fashion and Design. Who insists: “It is important, for the people of Milan, to see what happens behind the scenes of an industrial or artisanal creation. And for us administrators this constitutes a building block for the “Milan Manufacturing” programme which is intended to incentivise a return of “light manufacturing” to the city, with the objective of regenerating decommissioned areas and creating good jobs, allowing so many youngsters to transform their own creativity into ideas, projects and objects thanks to the ever wider use of new technologies, from 3D printers to laser cutters which render the creation of prototypes simpler and more economical”.

What shall we be able to see, in the seventy places where they “make things, and make them well”, in the factories, large and small, in which that type of entrepreneurship so typical of the history and current affairs of Milan is flourishing? Councillor Tajani explains: “From the laboratory which makes hats for the English royals to the factory which creates aluminium guitars for rock idols such as Lou Reed and Ben Harper, via the Pirelli laboratories where they create those legendary Formula 1 tyres, across to the mechanical workshop where they build by hand and with the assistance of new 3D printers the components needed to bring life back to classical one-off models, or discovering the secrets of the bookbinder’s art or how a ring is created in a goldsmith’s laboratory or how a pair of hand-made shoes is made”.

The full list of participants in the event can be found at www.manifattura.milano.it. Here at Pirelli, in particular, the programme for 29th September includes guided tours of the laboratories for research, development and experimentation in the Bicocca Headquarters, where it will be possible to see how a prototype tyre is created, by combining innovative technologies with manual expertise, and to witness several tests among those used by Pirelli to develop road and racing tyres. An Italian level of excellence of international value.

Milan, the greater Milan of the whole metropolitan area, undergoing a transformation into a smart city on a global scale, is still an industrial city, in which manufacturing accounts for 29% of GDP (Gross Domestic Product), much more in fact than the national average (17%) but also more than the German average (22%). And this is manufacturing undergoing major change, at the heart of a true digital turning point for the economy, according to the criteria of “Industry 4.0”: manufacturing is combining with hi-tech services, sophisticated production capabilities are improving their own competitiveness thanks to a robust contribution from research centres, industrial competencies are being reinforced thanks to the support of the “knowledge economy” strengthened by universities (the Polytechnic university, Bocconi, Cattolica, Statale, Bicocca, Humanitas) which are achieving notable rankings among the best international centres for training and research. The mechanical sector is becoming the mechatronic sector, we are achieving high levels of productivity in rubber and plastics, automotive, chemicals and pharmaceuticals, life sciences and indeed in the traditional “Made in Italy” sectors – clothing and fashion, furnishings and the food and agriculture industry. Industrial Milan means avant-garde modernity and the possibility of a good future.

Stefano Micelli, an economist who is attentive to all the phenomena of “Industry 4.0”, and chair of the Milan Manufacturing Advisory Board, maintains: “Visiting workplaces and manufacturing sites allows people to discover the vitality and quality of the many businesses and artisanal workers that give life to the city of Milan. The purpose of the event is to create an ever greater awareness about the economic and cultural wealth which these activities represent and to underline their growth potential. The initiative is aimed especially at those youngsters who are looking for job opportunities at the current time: the manufacturing sector which is active in the city needs their talent in order to develop design and technological innovation”.

Culture, technology, economic development. As is explained by Marco Taisch, Scientific Chairman of the “World Manufacturing Forum” (the Foundation which promotes it is a prime example of collaboration between businesses, the academic world, institutions and the associative world in order to cultivate and disseminate culture across the manufacturing sector): “Manufacturing is the primary generator of wealth and social equilibrium, as a means to the further development of advanced economies and also as a fundamental tool for the growth of less developed areas of the world”. The Annual Meeting in Cernobbio of the “World Manufacturing Forum”, programmed for 27th and 28th September (in collaboration with the Chamber of Commerce of Milan, the Assolombarda association, the Confartigianato artisan confederation, ANCE and a series of other business and research organisations), will attempt to “determine and influence, at a European and global level, scenarios for the future, by looking into the significance of the innovations which from the manufacturer will also have an impact on services as well as on people’s lives. For these reasons, the twinning of “Open production facilities” and the WMF constitutes a natural partnership based on the sharing of objectives to be achieved together through the exploitation and development of urban and regional manufacturing in an international perspective”.

Especially on Pirelli’s part, there is particular attention placed on the connections between manufacturing and digital processes. The whole Group has for many years followed the processes which lead in this direction, in the context of a “polytechnical culture” which interprets innovation as a general commitment which links together products, productive processes, materials, industrial relations, and the languages of research, of marketing and of communication. And significant indications of this can also be found in a document which brings together company results and indicative forecasts: the Consolidated Accounts 2017.

Pirelli’s digital transformation, in the Accounts, is set alongside five stories of “artisans 4.0” who have taken advantage of digital transformation to find the key to increasing their own activities (we shall discuss these in more detail shortly).And the heading is exemplary: “Data meets passion”, to confirm and re-launch the company’s tradition of explaining the accounts over and above the numbers by referring to art and literature. On this occasion the artistic and cultural contributions, in order to show how the digital world radically changes cultures and customs within society and within individuals, are those of the artist Emiliano Ponzi and of three writers of international renown: Mohsin Hamid, Tom McCarty and Ted Chiang. And these are the stories of the five digital artists, with business ideas reinforced by advanced technological models: the “3Bee” (a hi-tech beehive which, through sensors, monitors the entire production cycle of the hive including remotely), “Alter Ego” (thanks to 3D software it produces ecologically sustainable made-to-measure surf boards), “Demeter.life” (by utilising blockchain technology a direct relationship is established between consumers and farmers throughout the world in order to improve sustainable crops), the “Druetta Upholstery” (the re-launch of the family business using 3D planning and virtual rooms for the design of made-to-measure furnishings) and “Differenthood” (an on-line platform where, based on 5 thousand fabrics and with over 1 billion possible combinations, people can create garments which are unique and 100% Made in Italy, and which can then be shared with the community).

There is then, in the Pirelli Consolidated Accounts 2017, alongside the company data, a general indication about the values of “making things”, in the digital world. And there is the story-telling. With strong literary and political implications. As Tom McCarthy confirms: “within the rise of the digital culture…. it is politics which becomes a literary matter. Literary in the sense that public life – and private life – finds itself governed by its own transcription: when everything is noted down in a register of some sort, then experience as such, and with it the problem of free will (are we masters of ourselves? Or are all our actions and our decisions governed and decided by algorithms?), is reduced to instances and acts of scripture”.

The summary? Open production facilities, precisely. And words to continue to make them live on.